The Value of Proportionate Fines

Why do most governments issue the same fines to both plutocrats and paupers?

Thank you for reading The Garden of Forking Paths. If you value my research and writing and want to support my work, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription for just $4/month. It will also give you full access to 200+ essays in the archive. Or, alternatively, check out my award-winning book: FLUKE. I rely exclusively on reader support to write for you.

A few miles from my house, there’s a little indentation off the road, just large enough for a few cars to quickly pull in, without blocking traffic, while dropping someone off at nearby bars, restaurants, or the community arts centre. Most of the time, it’s an empty little spit of asphalt, clearly marked with double yellow lines that prohibit parking. Every so often, a disabled or elderly person gets dropped off on the sidewalk, able to enjoy a more convenient evening out that they might have otherwise foregone.

But now, when I drive by that spot in the evenings, I’m often met by the garish sight of an illegally parked mantis green McLaren supercar in front of another illegally parked Ferrari, decked out in racing red. The former retails for around £215,000 ($292,000); the latter for a more modest £178,000 ($242,000).

Lest you mistakenly (and improbably) imagine these supercars to be owned by a selfless hospice nurse, let me disabuse you of that mental image: they’re the flashy metal pride of an animal abusing capitalist cliché, a local business baron who previously got banned from the road for four years after getting caught drunk driving in another flashy car—twice within two weeks.

These are the sort of people who, I imagine, devote their limited brain cells to pondering cryptocurrency memecoins while openly wondering why the government can’t just kill the poor.

The supercars are parked in front of the local baron’s brash new wine and cheese bar that learned its sense of both style and ethics from Trump University and—surprise, surprise—prides itself on serving foie gras, the byproduct of force feeding geese and ducks until their livers balloon to ten times the normal size.

But when I drive by, I’ve also started noticing another colorful sight attached to these supercompensating supercars: a neon yellow parking fine notice issued from the local council, charging the owners £50. For them, it’s less than a slap on the wrist; the McLaren owner could park illegally every day, 365 days a year, for 12 years—a significant proportion of his life—and still not fully reach the amount he paid for his grotesque steel status symbol.

The owners have clearly done the math, liked the sums their phone calculators spit out, and decided to use the stretch of asphalt normally reserved for dropping off little old ladies as their personal illegal parking bay. After all, when you’re rich enough, parking fees and parking fines become proportionally identical as a share of one’s monthly income: approximately zero percent.1

As one sociopathic millionaire TikToker—a loathsome social leech who presumably sees other humans as wallets with a pulse—recently put it:

“Broke people see a fine, but I see VIP parking.”

This dynamic raises the obvious question: if government fines exist to deter illegal and unethical behavior, why do most jurisdictions impose the same financial penalties on billionaires and beggars, plutocrats and paupers?

Fines from Ur-Nammu to the Soviet Union

As long as humans have had law codes, fines have been issued. In the oldest surviving legal code from ancient Mesopotamia, the Code of Ur-Nammu, fines were imposed even as punishment for physical harm, such that there was a set financial penalty—half a mina of silver—if you happened to knock out someone else’s eye.

This example quite vividly showcases that the notion of “an eye for an eye” was a later norm, first appearing several hundred years later, in the laws of Hammurabi. However, the Hammurabi law code also imposed proportional fines for stealing, relative to the value of the object, such that the thief must be made to repay five times the value of a stolen item, unless it was livestock (ten times), or, even worse, a royally-owned object (thirty times).

But fines require at least two competencies to be effective: states powerful enough to collect them and criminals rich enough to pay them.

Neither criterion could be taken for granted historically, so many Western European states in the medieval period simply opted for the barbarity of dank jail cells or brutal punishments—including torture. Debtors prisons were another notorious method for ensuring that poor criminals faced harsh consequences while the affluent were less affected.

By the closing years of the 19th century, however, campaigners began to rail against the ineffectiveness of short-term prison sentences for minor crimes, which fostered recidivism, destroyed families, and drained the state rather than enriching public coffers.

This reformist viewpoint, combined with greater state capacity and a rise in incomes, led to a resurgence of the punitive fine in many European states. There remained, however, resistance to fines in most communist countries, including the USSR, where fines were viewed as an extension of capitalism, in which everything—even criminality—came with a price tag. As a result, for much of the Soviet Union’s heyday, fines were only imposed in about three to four percent of criminal punishments, a rate far lower than in Europe.

The United States, which prides itself in being an outlier—in portion size, car size, and in unapologetically insisting that “cheese” is something that can be sprayed out of a pressurized can—yet again bucked the European trend.

American criminals, broadly speaking, went to prison, whereas fines became the punishment meted out to corporations. As a result, according to one analysis in the early 1980s, with “a broad repertoire of offenses attracting criminal fines more than half the time in Britain and more than three quarters of the time in Germany attracted sentences of fines in only 5% of cases in USA at the federal level.”

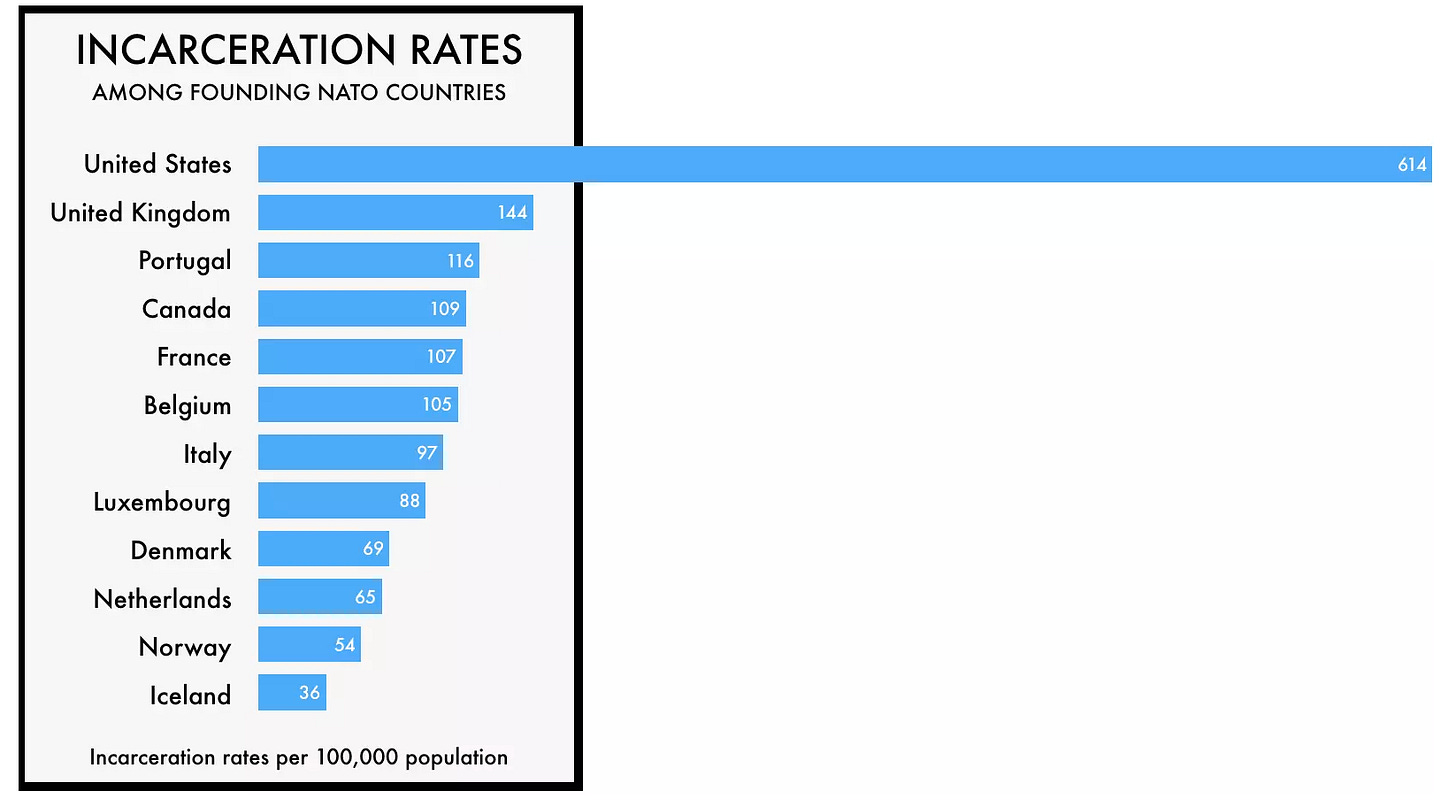

This provides a partial, albeit admittedly incomplete, explanation for why American incarceration rates are astronomically higher than peer nations.

And yet, government fines as a source of social deterrence are neither inherently good nor bad; their utility is tied to their design. Unfortunately, the aforementioned supercar problem—of fines that do little to deter or punish terrible behavior for the rich—extends to the corporate sector as well.

II: Missing the Target

Last November, 27 year-old Brianna Burley-Inners, a nature-loving photography enthusiast and animal lover who used to serve meals to elderly people in a care home, went to work at the Target store near her home of South Williamsport, Pennsylvania. Brianna’s social media profile reflected her personality and her profession with a charming four-part tagline:

Verified dog enthusiast. Avid pop-punk supporter. Just trying to make it out alive. Works at Target.

Around 11:30pm one night, Burley-Inners was tasked with elevating herself near the ceiling on a manlift, to wipe clean the lenses of the store’s security cameras. Half an hour later, her colleague asked her on the walkie-talkie whether she was done, but received no response. Checking on her, the colleague found her hunched over, dead, pinned between the lift and the door frame, her small body crushed to death by “compressional asphyxiation.”

After a thorough workplace safety review, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration determined that Target was guilty of a “serious” violation of workplace safety, one that could, or was likely to, “cause death or serious injury.” It led to the imposition of the maximum fine for a “serious” violation:

$16,550.

Lest that seem like a corporate pittance, Target also received a $13,005 fine for failing to report the death to OSHA in a timely manner, for a grand total of $29,555.

Target’s annual revenues for 2024 were $107,000,000,000—$107 billion—meaning that the $29,555 penalty represents 0.000024% of the company’s annual revenues. Put another way, the OSHA “punishment” for Target was the equivalent of imposing a 24 cent fine on someone who earns a million dollars a year. A slap on the wrist, delivered with the solidity of a soap bubble.2

There is a better way. It’s called the “day fine,” and it’s been used—in some more enlightened parts of the world—for over a century.

III: The €121,000 Speeding Ticket

In 2023, the 76 year-old multimillionaire Finnish businessman Anders Wiklöf accidentally failed to slow down as the speed limit switched abruptly from 70 km to 50 km/hour. He was clocked going 82 km/hour in a 50 zone, significantly over the legal limit.

Because of his excessive speed—and because Wiklöf had twice been cited for speeding previously—the Finnish fine levied would be higher than normal. But rather than increasing from what you might expect, say, from €150 to €250, Wiklöf’s penalty was a bit steeper: €121,000, or roughly $138,000.

Finland, like several other countries in Western Europe, uses the “day fine” system for calculating the financial value of state-imposed penalties. The method is straightforward.

First, determine the severity of the crime and how many days worth of work should be deducted from the person’s earnings. A small penalty might be half a day or a day; for more serious offenses, a bigger penalty might be dozens, even hundreds, of days.

Second, multiply the number of days by that person’s daily income, providing the overall value of the fine.3 (Various models can be used to account for wealth, income, or both).4

A one day fine for a person who earns $30,000 per year would be $82; a one day fine for a person earning $1 million per year would be $2,740. The idea is that the penalties, while different in absolute terms, impose the same relative consequence on both people. Each loses a proportionate amount of their income, creating a similar deterrent for each violator.

The notion of income-proportionate penalties is nothing new. In Anglo-Saxon England, the principle was most clearly defined not in terms of fines, but in terms of the worth of a human life. The wergild, or “man price,” was a fee that was paid in recompense for killing someone, with the fee adjusted to match the social rank of the victim.

Over time, though, the principle was flipped, not to compensate rich victims with more money than poor ones, but to ensure that rich perpetrators paid more so they too faced real, biting consequences for their actions. Income-adjusted penalties became more commonplace in 13th century England.

Hundreds of years later, the great 18th and 19th century moral philosopher Jeremy Bentham—whose corpse is preserved and on display in a glass box right by my university office—explicitly made the case that only proportionate fines were truly just:

“Pecuniary punishments should always be regulated by the fortune of the offender. The relative amount of the fine should be fixed, not its absolute amount.”

As Elena Kantorowicz-Reznichenko of Erasmus University Rotterdam explains, Finland took that principle seriously first, pioneering the modern day fine in 1921. The adoption, however, was not done out of a thirst for fairer justice, but as a mechanism to deal with collecting revenues in a time of high inflation. Fixed penalties would evaporate in value due to a collapsing currency, whereas proportionate punishments could keep pace with changing monetary values.

Sweden and Denmark followed Finland’s lead in the 1930s. Nonetheless, day fines remained relatively unusual in Europe until more recently.

Germany, which now uses a complex day fine system, conducted a rigorous evaluation after adopting the new system, to see how it performed. As Kantorowicz-Reznichenko points out, while day fines did little to deter career criminals, it turned out to be more effective at reducing repeat offenses among everyone else. And because the fines were tethered to one’s ability to pay, collections went up, defaults went down, all saving the government the administrative overhead of trying to track down unpaid fines.

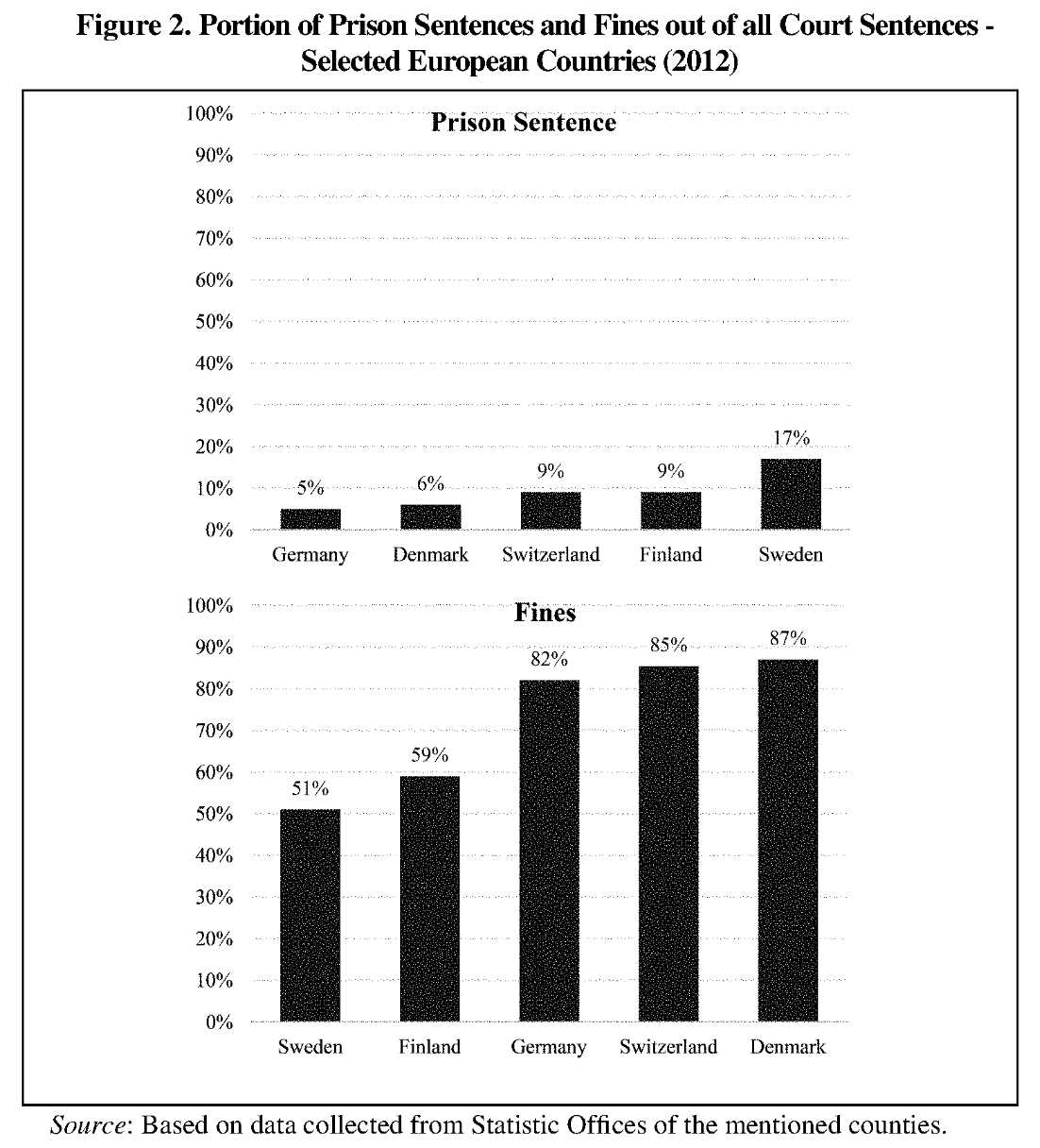

Furthermore, her data, as shown in the graphic below, illustrates just how much these scaling financial penalties are now used as an alternative to short-term incarceration in countries that have become the main hubs of day fines.

In Britain, the Tory government of the early 1990s briefly instituted limited day fines, but they were binned after modest public backlash to some high-profile cases of variable fines. In one instance in West Yorkshire, “two men convicted over a street fight paid £640 and £64 respectively, based on their income brackets.”

As for the United States, several jurisdictions experimented with day fines, mostly in the 1980s. From Staten Island to Milwaukee, the experiments were a success, boosting payment rates, raising revenue, and creating a meaningful deterrent that more equally affected everyone in society. In Polk County, Iowa, “the level of full payment rose from 32% (fixed fines) to 72% (day-fines).”

So, why didn’t they stick?

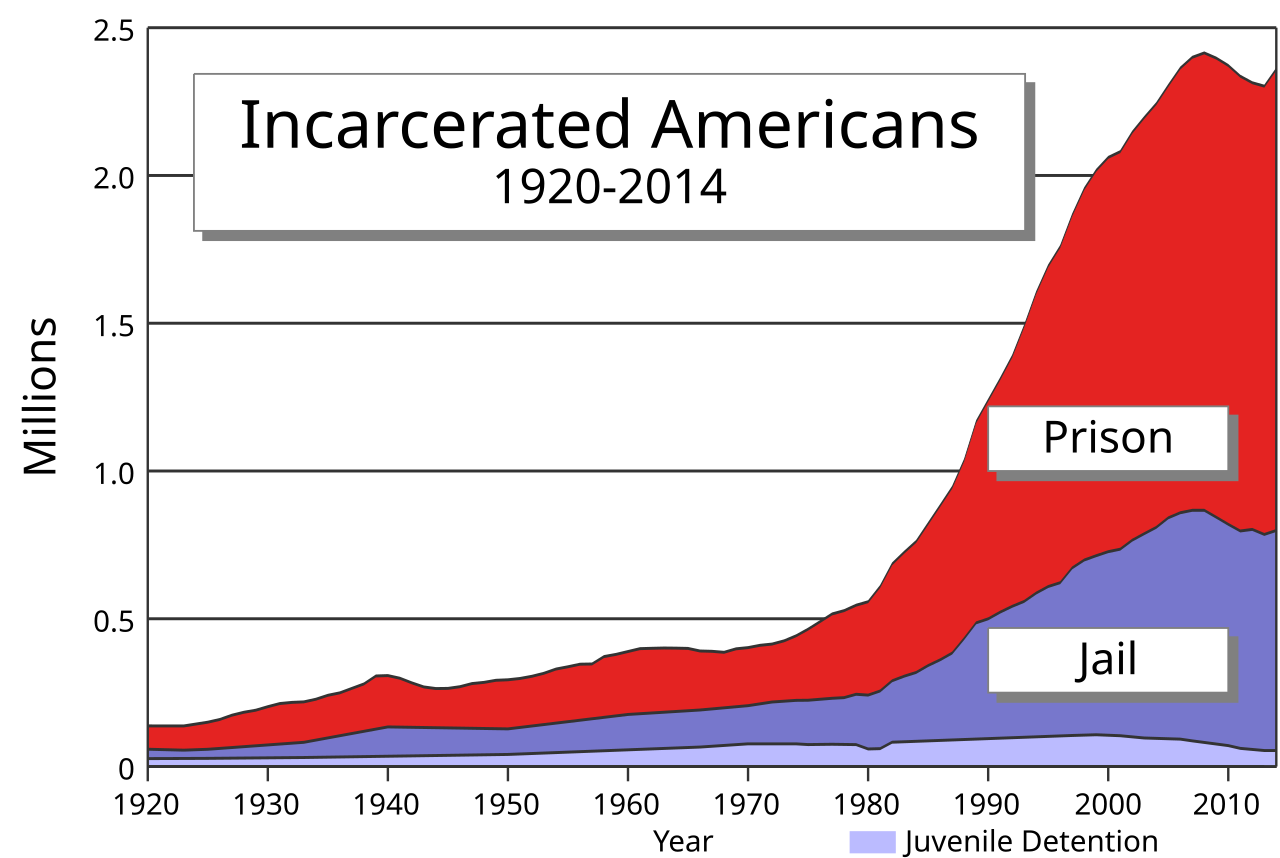

Most analysts chalk it up to the “tough on crime” turn in American politics during the Reagan years, when empirical evidence took a back seat to vindictive retribution as the lodestone for US criminal justice policy. Why fine someone when they could go to a perfectly horrid prison cell instead?

The below chart tells that unfortunate tale better than prose ever could.

IV: Redefining Equal Justice

There is, in my view, a rather warped critique of proportional fines, which brands them as a form of unequal justice. The same crime, they say, should always have the same punishment.

But that’s an absurd inversion of the principle of equal justice. Imagine a punishment protocol that applies the same penalty to every offender: each criminal must line up against a wall, at which point a horizontal guillotine will slice toward them, exactly six feet off the ground. For shorter people, there will be no punishment; for others, a harrowing haircut; and for those much above six feet, death. The “same” punishments often have differential effects.5

This is, of course, unavoidable. Even incarceration may feel like more of a punishment to some people than others, offering more crushing despair for the illiterate extrovert than the introverted bookworm. But while some variation is inevitable, most non-monetary forms of punishment at least have objective downsides; few people in the world are indifferent to incarceration the same way that the local business barons driving garish supercars don’t care at all about lowball parking fines.6

And if the evidence suggests that proportionate fines can serve a useful social purpose—of deterring crime across the social spectrum—while generating higher revenues for the state and decreasing the costs of potentially ineffective incarceration for more minor offenses, well, that’s a no-brainer.7

Whether it’s ensuring that corporations pay more than an undetectable rounding error in fines when they are deemed responsible for the death of an employee, or stopping selfish slimeballs from treating public roads as their VIP parking spots, our goal in engineering social deterrence should not be to make uniform punishments, but to ensure that breaking social rules and committing crimes are uniformly unappealing—for rich and poor alike.

Thank you for reading The Garden of Forking Paths. This edition was for everyone, but if you value my work and want to support it—and fully unlock 200+ essays from the archive—then please consider upgrading to a paid subscription for just $4/month. Or, consider buying my book: FLUKE.

For my previous discussion of a wonderful illustration of how parking ticket policy can provide crucial lessons into corruption, see this adapted excerpt of my book Corruptible, which draws on a stellar research study by Fisman and Miguel.

Even for “wilful or repeat” violations, the maximum fine is just $165,514.

In Finland, the actual equation for a day fine is a bit more complex, but it works out to about half of the person’s daily net income.

There are a variety of clever and fair ways to deal with implementation problems that would otherwise shield wealthy people from hefty day fines.

I was inspired by a variation of this example from an astute comment in a Reddit thread, but the user deleted their username, so I can’t credit them directly.

Criminal justice is, in many ways, an empirical problem masquerading as a moral one. Our obsession with allocating blame and ensuring retribution can sometimes blind us to evidence that shows that some purely retribution-based approaches actually increase the number of future victims by perpetuating the cycle of crime. This doesn’t suggest we should be “soft on crime,” but rather that evidence and experimentation should determine the best policies. My core guiding principle with any question of criminal justice is this: is this likely to increase or decrease avoidable future suffering? (Bentham, a pioneer of utilitarianism, would be proud).

This is what Michael Scott from The Office craves: a win-win-win solution. (Oscar will wear the poster as a t-shirt).