Is America Still on the Path to Authoritarianism?

The worst election deniers were defeated in the midterms. Trump is calling to terminate the Constitution. Is America heading toward authoritarianism? If so, can the trend be reversed in time?

Five years ago, I wrote the first book arguing that Donald Trump was an authoritarian who posed an existential threat to American democracy. I was called an alarmist, a fantasist, someone who engaged in hyperbole. “Donald Trump may be a blowhard, but he’s hardly an aspiring despot in waiting.” I faced plenty of eye rolls, or accusations of “Trump Derangement Syndrome.”

Not so much of that now.

Trump took just about every page out of the despot’s playbook: demonizing minorities, calling journalists the “enemy of the people,” appointing family members to senior government posts, lying constantly, spreading deranged conspiracy theories, cashing in on the presidency, trying to pressure election officials to “find votes,” and inciting a mob to storm the United States Capitol on January 6th to stay in power.

Over the weekend, Trump went full despot, calling on his Truth Social network to suspend or terminate the US Constitution. But even then, many Republicans refused to rule out supporting him for president in 2024 if he were the party’s nominee.

On the other hand, the most reliable barometers of democracy are elections, and the midterm elections went surprisingly well for the forces of democracy. There was much to celebrate, due to the hard work of a lot of people who worked hard to protect democracy.

The worst election deniers, zealots such as Doug Mastriano of Pennsylvania, Kari Lake, Blake Masters, and Mark Finchem of Arizona, and Tudor Dixon of Michigan were all defeated. Democrats retained control of the Senate and only narrowly lost the House. Hell, even Lauren Boebert (R, AK-47) almost lost.

So, where does that leave us? Is American democracy saved? Is our long national flirtation with authoritarianism over?

I’m afraid I must disappoint you. We’re still in serious trouble—and the specter of authoritarianism will continue to loom large for many years to come. Many of you already know this. But I want to walk through the arguments behind that claim, so we can better understand the threat and learn how to combat it. And I promise that before I end this post, I’ll explain why there’s room for optimism and hope.

But first, let’s understand the scale and scope of the authoritarian threat in America.

I often compare democracy to a sandcastle. In the past, democracies were destroyed in a single big wave. It could be a coup, a civil war, a revolution, or an elected dictator seizing power. But those ways of destroying the sandcastle are rarer these days. Instead, the tide comes in very slowly, and each wave laps away at the sand castle, taking a few grains of sand with it each time.

It’s so much slower than the forces that people picture when they think of democracy being destroyed that most people in the country don’t even notice the damage that’s been done.

But sure enough, America’s democratic sand castle has eroded, slowly and steadily. The tide has come in particularly high since 2016. We’ve repaired bits of the ramparts here and there, but it’s still very much at risk of being washed away.

The optimistic take on the recent midterm elections goes something like this: there were several completely crazy Trump disciples in swing states who, if they had won, would’ve been able to deliver the state’s election to him in 2024. They lost, almost uniformly, thereby saving democracy to fight another day. Americans built, in the sandcastle analogy, flood defenses.

That optimism misunderstands the core problem. The threat to American democracy does not come from a few individuals. It’s not as though defeating Kari Lake or Doug Mastriano is sufficient to stave off authoritarianism. They ride the waves, but they are not making them.

I would summarize the threat like this:

The threat to American democracy comes from an authoritarian political movement that has embedded itself within the base of the Republican party in the Trump and post-Trump era. It is further enabled not just by Donald Trump, but by Republican elites who either are authoritarian themselves, or act authoritarian to win elections.

The GOP is no longer the party of Bush, McCain, and Romney.

Problem 1: The inevitable victory of an authoritarian party in a two-party system

If one of the two parties in a two-party system becomes authoritarian, then the only way to truly protect democracy is to block that authoritarian party from ever wielding unified power. But that’s impossible to do indefinitely. Eventually, the authoritarian party will win. Even when the Democrats over-performed expectations in the midterms, they still lost control of the House. (A huge chunk of the Republican House voted against certifying the 2020 election, which, objectively, was an attempted authoritarian power grab).

The only sustainable way to protect democracy is therefore to reform the Republican party and bring it back from its shift toward authoritarianism. That doesn't just require defeating specific candidates. It requires changing the behavior of Republican leadership and the political attitudes of MAGA voters, which will take a long time.

Problem 2: Some election deniers lost. Far more of them won.

According to the Washington Post, roughly 60 percent of election deniers, or as I call them, authoritarians, won their elections in the midterms. That’s 178 major candidates who exposed themselves as authoritarian zealots willing to overturn an election without a shred of credible evidence. Voters nonetheless put them in power.

If Americans want to shore up democracy, they can’t write off entire states to the whims of would-be autocrats. In a federal system, huge swaths of policy are made at the state level. But a lot of deep red states are now run by some pretty extreme people.

Making matters worse, we don't know which states will be battlegrounds in 2028 or 2032. A lot of people might have shrugged if an authoritarian had become secretary of state in Georgia in, say, 2012, but it turned out to matter enormously who was in that position in 2020. We can’t forecast which states will be battlegrounds in the future, and we’re currently losing control of some states to people who have shown that they will willingly work against the democratic process.

Put differently: Kari Lake and Doug Mastriano were visible threats, but a lot of less visible threats slipped in under our radar.

Problem 3: The midterm defeats were not landslides

Except for Doug Mastriano, none of the important midterm defeats were landslides. They were close. That matters, because destroying authoritarianism requires a sea change in the political strategies of any authoritarian party. If we want to get Republicans to stop pursuing anti-democracy strategies, they need to not just face defeat at the ballot box, but an absolute drubbing.

Instead, Kari Lake very nearly won, after making Trump and election denial a centerpiece of her campaign. And that was in a state that Biden won. Until such zealots are defeated in landslides, the Republican base will continue to flirt with a authoritarianism.

Problem 4: Trump fever hasn’t broken

As I wrote previously in this newsletter, Donald Trump maintains extreme influence over the Republican base, because much of his allure functions like an authoritarian cult of personality. Even after he explicitly called to terminate the Constitution following hosting two Holocaust-denying anti-Semites at Mar-a-Lago, many senior Republicans still won’t condemn Trump by name.

Trump’s influence over his party is waning. But his social media posts on Truth Social are getting more deranged, more authoritarian, and more explicitly pro-QAnon.

He will need close to a majority of Americans to become president again, which currently looks unlikely. But he’s still got a very loud megaphone, he’s speaking directly to millions of well-armed extremists, and his calls to overthrow American democracy are becoming increasingly explicit.

Make no mistake: Donald Trump is diminished, but not defeated, and he still poses an existential threat to democracy.

Problem 5: America now has millions of “authoritarian voters.”

In the aftermath of World War II, and during the Cold War, Americans were constantly bombarded with reminders of how precious democracy can be, because we compared ourselves to the alternative: the Nazis and, later, the Soviet Union. But since the early 1990s, the autocratic villains have been less clear-cut, allowing a democratic relativism to take root, particularly in the base of the Republican Party. Remember when Trump was asked about Putin in 2017? His response was moral relativism: “There are a lot of killers. You think our country’s so innocent?”

Some voters don’t care about policy or procedure, they just want to win—even if it means taking a wrecking ball to democracy or never holding another election again. They’d happily have a dictator, so long as it’s their dictator. In political science, these are known as “authoritarian voters.”

They’re particularly worrying, because many of them will long outlive Donald Trump. Once you have primed a voting base to applaud authoritarian politics, they get a taste for it, and that becomes a thirst.

If Donald Trump loses in 2024, or exits the political scene for whatever reason in the future, Pandora’s Box of authoritarian voters doesn’t magically close, returning everything to normal. Even in the post-Trump era, a generation of Republican voters will crave a candidate who behaves like Trump. The demand for authoritarian politics will not soon diminish.

Problem 6: American democracy is structurally dysfunctional

American democracy has structural problems—even though these are problems that have been solved in every other advanced industrialized democracy on the planet.

Election administration is not rocket science, and voter registration, voter suppression, and gerrymandering are not severe problems in most other democracies. Maintaining the grotesque role of money in politics is also a political choice. The Supreme Court plays a politicized role in American politics that is unlike how courts operate in peer democracies. Our primary system combined with uncompetitive elections creates incentives for extremism, as candidates seek to differentiate themselves from the pack.

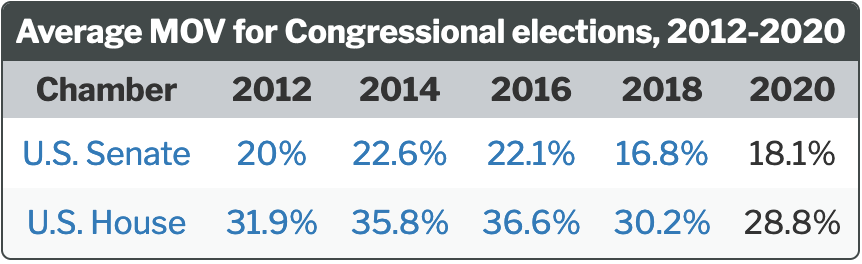

We also have built a largely gerrymandered system, made worse by demographic sorting (where like-minded people live in close proximity) such that most elections are uncompetitive. Take a look at this chart from Ballotpedia, which shows the average margin of victory for US House and Senate races over time. This matters because when democracy lacks competition, compromise dies and extremism thrives.

We have decided, as a country, to maintain cracks in the democratic system that have long ago been filled in other rich democracies. None of that was fixed because Kari Lake lost in the midterms. We still have to fix the system, because those problems were around long before Donald Trump descended from his golden penthouse in 2015.

Problem 7: Extremism begets extremism

When democracies enter an authoritarian death spiral, there is a risk that the response to it from otherwise reasonable people will itself become extreme. So far, the Democrats have done a reasonably good job of avoiding that – Joe Biden, who has taken the left-centrist lane for his entire political career, could hardly be considered an extremist.

But at some point, that forbearance might end. What’s going on at the US Supreme Court is extreme, especially by international standards, and the country is going to be prone to long periods of minority rule, where an influential minority is able to wield power because of gerrymandering, the fact that the Senate isn’t tied to population, and the Electoral College – each of which distorts the political power of the majority viewpoint. At the moment, the extremism in elected American politics is coming from the right, but there could, at some point, be a backlash from the left (even if it’s on the fringes) that is also extreme and authoritarian, which would accelerate democracy’s death spiral.

What can be done?

All is not lost. The good news is that there are straightforward solutions. The bad news is that it is currently nearly impossible to pass them. At some point, though, there may be a window, and we’ll need to have leaders with the urgency and political courage to do so. In the meantime, at the state level, a lot can be achieved.

Here are some ideas for key reforms:

1. Reform the Electoral Count Act. You can read what that might look like here.

2. Reform primaries. I’ve previously written about how open primaries can moderate extremism and give candidates incentives to cater to more sensible voters.

3. End gerrymandering. It’s indefensible. Both parties do it, though Republicans have done it more in recent years. Efforts to gerrymander for 2022 were mixed for both parties.

4. The FEC should be reshaped to emulate Australia’s independent election commission. Our patchwork of election laws creates serious vulnerabilities that can easily be exploited.

5. The federal government should consider creating funding incentives that punish any election jurisdiction in which the average wait time to vote is longer than 30 minutes. As it stands now, voting wait times operate as a “time tax,” a burden that the poor are least able to bear. And studies have shown that minority-dominated neighborhoods face wait times that are six times longer than white-majority neighborhoods.

6. Turn some democratic norms into laws. The Nixon debacle ushered in a series of legislative reforms aimed at avoiding the lawlessness of his administration. The Trump era could leave that one positive legacy, if pro-democracy legislators chose to turn, for example, ethics norms into ethics laws. (And everyone who runs for president should be required to release their tax returns).

7. Establish an independent office to oversee politically connected pardons. This may require a Constitutional amendment, but it would be worth trying. The president’s ability to pardon people who would otherwise testify against him/her is a direct threat to rule of law.

Many more reforms will be needed, and the political prospects for any of the above are currently either dead on arrival or on life support. But there need not be despair, because this is a solvable problem. Every other rich democracy in the world has overcome the challenges that plague America. We know what to do—we just need to create the political will to shore up our democratic sand castle.

I’ll close with a thought about why democracy matters.

While researching authoritarianism around the globe, I’ve been lucky to meet countless brave victims of autocracy. I’ve grown used to hearing the voices of torture victims break, as they choke up while telling me what happened to them under the jackboot of a despot. I’ve gotten to know candidates for president or prime minister who have been beaten, nearly to death, for daring to challenge the regime. I’ve seen crushing poverty and hopeless repression firsthand, from Madagascar to Thailand, and Belarus to Tunisia.

And I’ve heard a variation of the same seven words time and time again from these brave men and women who dared to defy autocracy:

“You don’t realize how lucky you are.”

It’s far easier to heal an ailing democracy than to bring one back from the dead.

We are lucky, because democracy—flawed as it is—survives in the United States. And that survival is something that all of us who believe in democracy, American or not, have a stake in preserving.

Thanks for reading The Garden of Forking Paths. If you would like to support my work, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription ($5/month, or $50/ year; think of it as the cost of a monthly latte, but for your brain). If you have not yet signed up for the newsletter, it’s free to do so—and about half the posts will be freely available to you.

As before, quite enlightening. Thank you. I do wish, however, that the robot reader be able to apply inflection to the reading. Perhaps you might know the path that this request should be forwarded to.

I am also a reader of Heather Cox Richardson and Robert Hubbell. I am following you because of your long-range look at things. You do not have to provide that service for me to continue to read your column. I was hoping that as a contributor, you might know haw to forward such a request to the platform itself. Thanks for your reply.