The "Moronic Inferno" and "the Fidgets," OR Why My Phone is Now Black & White

Modern life is frenetic, fidgety, structured around routine dopamine hits. It's a serious problem. But is it new? And what are we to do? I present to you: a new theory of distraction.

Thank you for reading The Garden of Forking Paths. If you are a lovely person who would also like to handily disprove the flawed economic theory of “free-riders,” consider upgrading to a paid subscription. Stick it to those smug economists for just $4/month! What a bargain. And in the process, you make my writing sustainable.

I: A trouble in our pockets

Samuel Pepys, the English diarist who opened a window into daily life in 17th century London, was an early adopter of smartphone addiction.

This was an extraordinary feat, given that the iPhone wouldn’t be invented for another 304 years after Pepys died in 1703. But he, like so many of us, couldn’t resist the dopamine hit that coursed through his veins as he relentlessly checked his device, one hundred times per afternoon. On May 13, 1665, Pepys wrote:

But, Lord! To see how much of my old folly and childishnesse hangs upon me still that I cannot forbear carrying my watch in my hand in the coach all this afternoon, and seeing what o’clock it is one hundred times; and am apt to think with myself, how could I be so long without one; though I remember since, I had one, and found it a trouble, and resolved to carry one no more about me while I lived.

It was, of course, not a smartphone, but a pocket watch of which Pepys spoke, as he chronicled his familiar relationship with newfangled technology: an irresistible urge to check it constantly, a wondrous sense of how he managed to live without it previously, and then, a reckoning, in which he decries the device, resolving to never carry one again.

To the ghost of the long-dead Mr. Pepys, I say: amen.

I’m part of a generation that straddles the internet, as though we are collectively strapped and tied—only somewhat willingly—to an unruly horse that we cannot dismount. We are some of the last humans to grow up without the internet, as I can still recall the initial screeches of the sound of the internet, a concept my Gen-Z students find alien and bizarre. I still remember the shouts of annoyance—from my parents, sometimes at my parents—when America Online (AOL) disconnected after someone foolishly picked up the modem-connected phone line in a silly attempt to speak to a human through their voicebox rather than emojis.

How antediluvian!

But we are now in a moment of social reckoning in which we, like Pepys and his pocket watch, question whether the technology is good for us. Books that chronicle the poisoning of young minds grace bestseller lists. We try, but fail, to “unplug.” There are now even devices to contain our devices, lock boxes that physically block you from accessing the dopamine that lurks, beckoning to you, from your pocket.

I just took a hit of the stuff in between writing those sentences, injecting a little red notification into my veins, rattled by momentary withdrawal. Phew. Like a twitching, cocaine-addicted monkey, I needed my fix before I could focus enough to articulate my argument to you, dear reader, about whether we are all too distracted to function. (Some of you, fellow dopamine primates that you are, already scrolled past this, impatient to get to “the good bit.”)

So, should we try to slay distractions with ever-greater efficiency and optimized lifehacks that murder our arch-enemy: wandering minds? After all, they inhibit productivity, which as we all know, is the pinnacle of human existence.

I, too, am addicted to my phone; I hate it; and I should not be the one lecturing you on this because I am a hypocrite. Nonetheless, my argument has three parts:

The perils of technological distraction aren’t new, but the nature of them has changed—for the worse.

Distraction, harnessed properly, can be joyous, not destructive. It is not distraction that’s the problem, but the kind of distraction—and our mental state when we encounter it—that matters.

The 21st century Pascal’s Wager of Smartphone Usage is logically persuasive but difficult to enact, which is why I’ve turned my phone black and white and resurrected a (mostly) dumb phone—and you can too.

II: The Egyptian God Thamus, Seneca the Younger, and Zhu Xi took great care to warn us. We didn’t listen.

We have always been distracted—and worried about it. In Plato’s Phaedrus, he recounts the moment when writing was first invented. The Egyptian God Thamus, alarmed at the brain rot it will inevitably induce, issues a warning:

For this invention will produce forgetfulness in the minds of those who learn to use it, because they will not practise their memory. Their trust in writing, produced by external characters which are no part of themselves, will discourage the use of their own memory within them. You have invented an elixir not of memory, but of reminding; and you offer your pupils the appearance of wisdom, not true wisdom, for they will read many things without instruction and will therefore seem to know many things, when they are for the most part ignorant and hard to get along with, since they are not wise, but only appear wise.

We needed more reminders. “Attend the Lord without distraction,” the Bible tells us. As Joe Stadolnik chronicles in Aeon, Seneca the Younger worried that the “multitude of books is a distraction.” Zhu Xi, the 12th century Chinese philosopher, warned of what we now call “stolen focus,” arguing that “the reason people today read sloppily is that there are a great many printed texts.”

But Stadolnik finds the best quote, perhaps, in the writings of Petrarch, who warned that too many texts broke our brains, “frenzied by so many matters, this mind can no longer taste anything, but stares longingly at everything, like Tantalus thirsting in the midst of water.” (That image, of a thirst we can never quench, is all too familiar, as though one more meme, one more “dunk” or “like” on social media, could finally satiate us. It never does).

Similarly, the French thinker and statesman with the delightful name Guillaume-Chrétien de Lamoignon de Malesherbes—enshrined forever in a Paris Métro station as a small consolation for being guillotined in 1794—worried that social breakdown would follow from newspapers, as people began to consume the news individually, rather than in the community setting delivered from the pulpit. (In that warning, he foreshadowed the atomization of society through news consumed while scrolling alone on social media).

In short, as Ecclesiastes suggested, there’s nothing new under the sun. We’re all just panicking about the same stuff, on repeat.

And yet.

There is something new—and worse—about modern technology, particularly through smartphone addiction, social media isolation, and the polarization and conspiracism that has emerged from utterly toxic pipelines of information. I can tell you, with certainty, that I have never felt unhealthily addicted to newspapers nor books (shush, bank account). And while my mind has been immensely enriched by the vast sum of human knowledge available at my fingertips on dazzling screens, my brain has been discombobulated, gummed up, flubbed, muddled, and scrambled, which are polite ways of saying what I really mean.

This state of affairs poses an intriguing puzzle: if every new technology that creates novel intellectual stimuli has given the thinkers of the day reason to worry about distraction, then why is our version of distraction particularly harmful? Why do we all have this feeling in the back of heads that we’d like to get off the unruly horse, please, even as it promises to move us all forward toward progress?

III: A theory of distraction, good and bad

I have a theory.

Distraction is a term we use to represent many different features of human existence, some wonderful, others terrible. Reading a mystery novel on a beach can be one of the loveliest experiences there is, though it is sometimes derided by the Lifehack Bros™ as inefficient, mindless distraction.1 And then there’s the truly bad bit: doomscrolling, which fills us with a never-ending terror that always refreshes, passively filling our zombie-like minds with dread. But it doesn’t really fill them, because at the end, we always feel empty. It’s unfulfilling distraction.

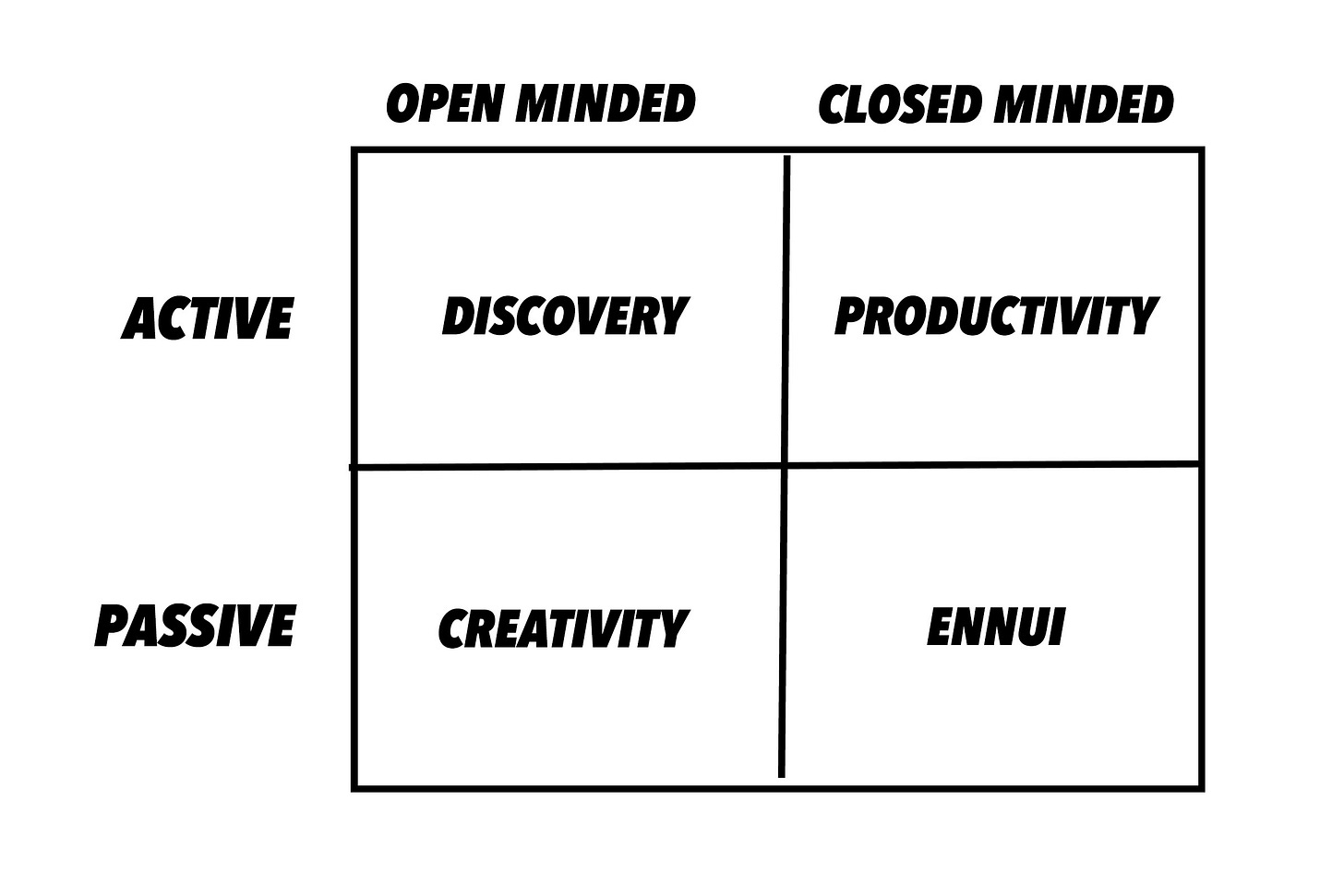

Social scientists like to use “2 x 2 tables” to illustrate concepts in a simplified form and I, having obtained the requisite doctorate from an accredited university, am licensed to use them. On one axis, we will have how directly engaged we are with the world: active versus passive experience. On the other, we have our mental disposition toward the world, whether we are open-minded or closed-minded.

Let me give you an example: when I go to a museum, as I sometimes do since I am a so-called “Man of the World,” I am actively seeking out knowledge that will tickle my brain. I am trying to discover something; my mind is open, inviting wonderful things to fall into it and stay a while.

Meanwhile, when I am engaged in the life-sucking task of techno-admin, such as trying to tell my water company call center representative that there must have been a digital billing error since I definitely did not use the equivalent of 4,000 baths last month, I am being active but closed-minded. I do not want to learn. I simply want to put my time to productive use to help my water company die a slow, excruciating death.

Herein lies the lesson: many of us are dissatisfied with our phone-based, internet-filled existence because it pushes us into two quadrants that we should only inhabit some of the time. Like a healthy diet, distraction is all about balance.

Behold!—the 2 x 2 table you never knew you were waiting for:2

Most of us are told to relentlessly inhabit the upper-right box, and then we cope with an overload of doing so by drifting into the bottom-right box. (Ennui, if you are not a fellow “Person of the World”—or are not a French speaker like the aforementioned, now-headless Malesherbes—means a deep feeling of weariness or dissatisfaction).

This is where we encounter something that I call the false prophet of focus culture, in which we are told to hustle, and then when we can’t focus, we are told that the proper “fix” to our brains is always training our minds to do more hustling—but slightly better. Worship your new god: Efficiency.

But what if that’s the wrong way to look at it? (Finally, here’s “the good bit”):

Look closely at the table! You will notice something: There are two other quadrants!

These left quadrants, in which our minds are open, but are either goal-directed toward active exploration (which often yields discovery) or passively enjoying our surroundings during a moment of reflection, or lost in aimless contemplation (which often yields creativity) are too often neglected when our dopamine fingers call the shots.3

Diderot once wrote:

“Distraction arises from an excellent quality of the understanding, which allows the ideas to strike against, or reawaken one another. It is the opposite of that stupor of attention, which merely rests on, or recycles, the same idea.”4

This framework gives us some appropriate nuance to reorient ourselves toward “distraction” in a more thoughtful way. It is not some monolithic demon to be slayed, but rather a joyful state of mind to embrace in the right way.

And yet, even when we try to engage in discovery, we often do so in such an over-the-top way that causes it to lose its value. We drift back into closed-minded optimization, extracting planned experiences from life, asserting control over the world rather than simply existing and exploring.

Did you really go to the Louvre if you didn’t Instagram the Mona Lisa? Did you really do a safari if you didn’t see lions and elephants like you were promised?5 What could have been a resonant moment of discovery can become yet another part of the hyper-optimized checklist existence, that, like a Tantalus-style thirst, never really gets completed nor quenched.

Oscar Wilde captured this dynamic as he discussed the ways in which our relationship with art has, for some, become about conquering the art, rather than letting it speak to us with an open mind:

If a man approaches a work of art with any desire to exercise authority over it and the artist, he approaches it in such a spirit that he cannot receive any artistic impression from it at all. The work of art is to dominate the spectator: the spectator is not to dominate the work of art. The spectator is to be receptive. He is to be the violin on which the master is to play. And the more completely he can suppress his own silly views, his own foolish prejudices, his own absurd ideas of what Art should be, or should not be, the more likely he is to understand and appreciate the work of art in question.

(Oscar Wilde, I can safely predict, would hate the Lifehack Bros). But his observation about art has broader meaning: what he calls receptivity is what I’m calling open-mindedness. These psychological states are where some of the most important emotions dwell: awe, wonder, and a sense of the majesty of life.

But here’s my dirty secret: I don’t practice what I preach. So, here’s how I’m trying to fix that—and how you can try, too.

IV: Pascal’s Smartphone Wager and Grayscale Screens

In 1798, Alexander Crichton previewed our smartphone problems when he wrote the aptly named An Inquiry into the Nature and Origin of Mental Derangement. He highlighted the problem of “mental restlessness” and explained how the most disturbed patients described their condition thus: they “say they have the fidgets.”

I confess: I have the fidgets and I want to escape, to borrow the wonderful term from Wyndham Lewis, from “the moronic inferno” that so much of social media and scroll culture has become. Whether

is right—or not—about the effect that smartphones are having on children (I suspect he is), I find his “Pascal’s Wager of Smartphone Usage” persuasive: if he’s right that it rots brains and causes despair and death, then he could be saving us all from the devastating effects of mental mush. However, if Haidt and his fellow Cassandras, are wrong, well, then you’ve just freed up some time in your day. No harm, no foul.So, I’m trying something new: I’ve turned my smartphone screen grayscale. Silly as it sounds, it makes it wonderfully boring, reducing its seductive allure. I have also reincarnated an old phone, wiped it clean, and put nothing but a messaging app on it, so my friends and enemies can call or text me, but there’s nothing else. (If you want to go for the nuclear option, buy a dumb phone).6

And, for the pesky apps that suck you into the dreaded quadrant of ennui, I’ve installed an app called “one sec” that delays my access for a few seconds as it patronizingly tells me “It’s time to take a deep breath.” (When I first did this, I was horrified at how instinctive my finger movements were when I unlocked the phone. I truly am a dopamine ape!).

I have not succeeded. I still spend too much time in the wrong quadrants. But I am determined to avoid the dark fate that awaits us if we passively drift through life as closed-minded consumers of that most dystopian word: content. For, if we’re not careful, we will end up as a creature so vividly described by Wyndham Lewis a century ago:

This forked, strange-scented, blond-skinned, gut bag, with its two bright rolling marbles with which it sees...I hang somewhere in its midst operating it with detachment.

Happy scrolling!

Thank you for reading The Garden of Forking Paths. Before you throw your device in a lake, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription, so I can give you little injections of discovery-style dopamine into your open-minded brain every so often for just $4/month. Or, go the old fashioned route, and experience my thoughts—gasp!—on actual physical paper, through the joys of reading FLUKE.

There is no actual trademark for that, of course. I just like how it looks, as though they’re a stupid brand of human, because they are.

You’ll be impressed to note that this majestic table was designed not with AI nor with the help of a skilled illustrator, but by yours truly.

I know this sounds like the kind of thing someone makes up to prove a point, but I thought of the ideas in the 2 x 2 table while running with my dog, the regal beast Zorro. I wasn’t thinking about this article and then poof! The idea fairy bestowed it upon me.

See this excellent essay by Matthew Bevis, which is where I found this quote.

Having done research across sub-Saharan Africa and explored amazing habitats, I was astonished to learn that safari companies sometimes guarantee tourists that they will see several of “the big five.” You can just imagine the entitled tourists demanding their money back, severing their lobe of discovery, as they insist: “I paid to see a rhino!”

I'm a psychotherapist, and I work with kids who struggle with electronic device addiction. We have spent a lot of time talking about device dependency/addiction, the neuropsychology of addiction (dopamine), analogizing it to other addictions for perspective, distinguishing it from other addictions to show how difficult it is to manage (because unlike an alcoholic, we can't completely abstain from electronics in modern society so it's like telling an alcoholic that he not only CAN have several drinks each day, but he/she MUST have several drinks each day........and just don't overdo it. Most alcoholics would go on a bender)....and to create awareness that their dependency/addiction to electronics is not a character flaw and does not make them a bad person (because this is how they internalize their addiction). From an evolutionary standpoint, tens of thousands of years of our neuropsychology has not and cannot evolve as fast as technology has in mere decades. Especially for kids whose prefrontal cortexes are still developing until around age 25. Unlike adults/the older generation who still struggle with device addiction post-development, the addiction is literally being wired into the brain development of kids/the younger generation. And worse, many of the algorithms are specifically designed to target the reward system (dopamine) of the brain to keep people on the site for as long as possible to increase advertising revenue. The kids literally have no chance against a system specifically designed by teams of engineers with knowledge of behavioral psychology to override executive functioning. I discuss this with my clients/parents in the context of "Youtube shorts" and TikTok videos, and the dopamine effect, which is related to "anticipation" and intermittent reinforcement......where it is anticipated the next 30/60 second video will be the coolest/funniest video they have ever seen, and if it's not, then the next will be.... and if it's not then the next will, etc. This is the same process that makes slot machines addictive for gamblers.

I have also thoroughly analyzed the role of dopamine/addiction in our political discourse, and the effect it has on tribalism, confirmation bias, and conspiracy theory susceptibility. This article is an overview of everything I've written about the topic, and even contemplates the effect whether GLP-1 agonist drugs (Ozempic) might mitigate toxic political "addictions":

https://www.patreon.com/posts/92826194

Up pops this substack from Brian and I stop coding to read it – so he’s distracted me (again) – but his articles are always in the discovery quadrant and that’s a very good thing (and the coding was getting intricate at the time but it’s creative). I enjoy reading his articles – he nails it in this one.

A long long time ago I got a degree in marketing and have distrusted advertising ever since. At a young age it was immediately apparent that I would be a diabolical marketeer and by accident I discovered computing and have spent my life in IT (in the productivity/efficiency quadrant I guess). I started my career before the internet and the PC – at the time a dozen colleagues were clattering away on their mechanical typewriters in the typing pool and I showed them how I used our IBM mainframe to write my reports on its word processor (a text editor in those days). Yes I am old. But here’s the thing, I am driven to create (build) things – always have been - I went to a school that wired me this way. I have never gamed and hardly ever used social media apps because they don’t interest me. For more than a decade, at the end of my career, I was director of IT at a leading global cyber security business, so I knew much about the mechanics of web applications, but colleagues were often taken aback by how little I understood about what, for example, Twitter was actually for (it was embarrassing frankly). Would it all have been different if I had started 20 years later and begun a device addiction like many kids and fuzzed my brain ? Probably. The most valuable use I make of the internet is to find out about things that make me curious. Back to the coding.