Jerome Powell and the Authoritarian Sirens of Odysseus

Why strongman presidents become weaker—to everyone's peril—when they remove constraints on their own power.

Thank you for reading The Garden of Forking Paths. This edition is for everyone but if you’d like to support my work, please consider upgrading for just $4/month, which also fully unlocks all 200+ essays in the archive. Alternatively, you can support my work by buying my book—FLUKE.

I: Precommitment against the sirens

Yesterday, The New York Times reported that Donald Trump had met with a small group of House Republicans to discuss his favorite dirty little economic fantasy: firing Jerome Powell, the Federal Reserve chairman that he previously appointed (but then forgot that he appointed).

However, to understand why firing Powell would be such a devastating event for American governance—and for the global economy—it’s first essential to explore why the world’s dictators are weakened by their inability to constrain themselves.

In Homer’s The Odyssey, Odysseus understands his own limits: he will never be able to resist the sirens while passing through their waters. Aware of the impending temptations, he orders his crew to tie him to the ship mast and not to release him. Paradoxically, by being constrained, he becomes more free.

This is a form of what the Norwegian philosopher Jon Elster calls precommitment, in which we liberate ourselves from the tyranny of our volatile whims by binding our future selves.1 If you’ve ever placed your cell phone halfway across the room to ensure that you’d get out of bed when the alarm goes off after a late night, you’ve practiced a form of precommitment.

Effective governments require both precommitment and another form of bounded decision-making known as credible commitment. The latter concept refers to mechanisms that ensure that people in a society believe that, for example, contracts, agreements, and threats carry weight because they are somehow predictably enforceable by an independent third party, most often the government.2

Successful leaders understand the lessons of Odysseus. Their power to unleash prosperity is tied to their ability to precommit the state to a given course of action, no matter the sirens that lie ahead—and their ability to credibly commit to policies that will predictably lead to real-world change.

Dictators, powerful as they may seem, are weak because of their inability to engage in either precommitment or credible commitment. As we’ll soon see, this is a key reason why lurching toward authoritarianism is so devastating for good governance.

In functioning democracies, however, these are solved problems.

Most countries avoid pure direct democracy because of worries about the tempestuous passions of the mob; voters elect representatives to act on their behalf within institutions

In turn, presidents and prime ministers are constrained by robust institutions—the Constitution, the legislature, the courts, the press, central banks, as well as elections—blocking elected leaders from making policy on a whim. As with Odysseus, these constraints liberate leaders to become more free. That way, true power lies.

Lashed to the institutional mast of democracy, they can govern effectively. Economies grow, as investors confidently put money at risk, understanding that layers of decision-making and predictable legal enforcement will protect them from the president waking up on the wrong side of the bed and upending everything.3 The worst human impulses of mercurial leaders are blunted, as they know that using Machiavellian criminality to dispatch rivals and crush opponents is a political dead end in any healthy democratic society.

By contrast, dictators are prisoners of their own whims. Autocratic leaders tie their enemies, not themselves, to the masts, then torture them. And that’s when the siren calls of dictatorship—abuse of power, corruption, personalized governance, murdering opponents, rigged elections, and economic mismanagement in pursuit of short-term gains—prove irresistibly seductive to those who inhabit gilded palaces.

Alas, as it turns out, the siren calls of dictatorship also seduce those who previously lived in gilded penthouses.

II: The dictator’s guide to firing Jerome Powell

In 2009, on the red-earthed island of Madagascar, a former radio disc jockey named Andry Rajoelina overthrew the reigning yogurt kingpin president, Marc Ravalomanana, in a coup d’état.4 In the aftermath, factories were burned down. Foreign contracts were canceled. International investors who sought to gain mining rights were suddenly subject to hidden “fees,” which turned out to be bribes to top government officials. Such extortion became part of the standard operating procedure of the Malagasy government.

During one of my research trips to Madagascar, I spoke to a government official tasked with courting international investors, to put their money at risk in one of the poorest and most coup prone countries on the planet. Asking not to be identified by name because of fears of being jailed (or worse), he leveled with me: “How can I convince investors,” he asked me, “when they know as well as I do that the president can just change his mind at any time?” Odysseus, this was not.5

Authoritarian rulers seek to project power by showing how unconstrained they are. But that’s the illusion of real power. It’s what truly keeps them weak.

Research by Anne Meng, a political scientist at the University of Virginia, demonstrates that authoritarian rulers who come into power in a weakened state often end up building more robust governance with stronger institutions. They do so not out of a desire for effective management, but out of necessity. To gain power, weaker rulers must bargain with rivals, so they give their opponents some say in governance—leading to the establishment of stronger legislatures, meaningful political parties, and better oversight.

By contrast, a fledgling dictator who holds the strongest political hand need not bargain with anyone. Power can flow solely through the individual, no checks, no balances. And that leads to a weakened personalized system that often undercuts economic growth—and collapses catastrophically when the dictator dies or is violently deposed.

In other words, seemingly weak dictators tend to build stronger regimes whereas seemingly strong dictators tend to build weaker regimes. In governance, some constraints amplify true power.

Now, let’s consider how these lessons apply, from Madagascar to Mar-a-Lago.

Trump’s tariffs—and threatened tariffs—have sparked higher inflation, which is what literally every economist predicted would happen. That has led to the Fed’s reduced appetite for lower interest rates.

The Fed—and Powell specifically—are worried that any efforts to supercharge the economy by reducing the costs of borrowing and investment could lead to further inflation during a period when it has already been historically elevated due to the global shock of Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.

Trump’s impulses—his internally narcissistic sirens—are loudly wailing against Powell, who dared to challenge the wisdom of Trump’s boneheaded tariffs. But if Trump crosses the political Rubicon and fires Powell, he will find himself in the disastrous economic terrain most familiar to the world’s megalomaniacal dictators.

Central banks can act as a crucial form of Odyssean mast tethering. Because lowering interest rates can prove politically popular in the short-term, unconstrained leaders find themselves tempted to manipulate monetary policy according to their self-interested whims. Whether there’s a looming election or a crisis that threatens their political survival, politicians who care more about themselves than about the country might use monetary policy as a tool to strengthen their grip on power.

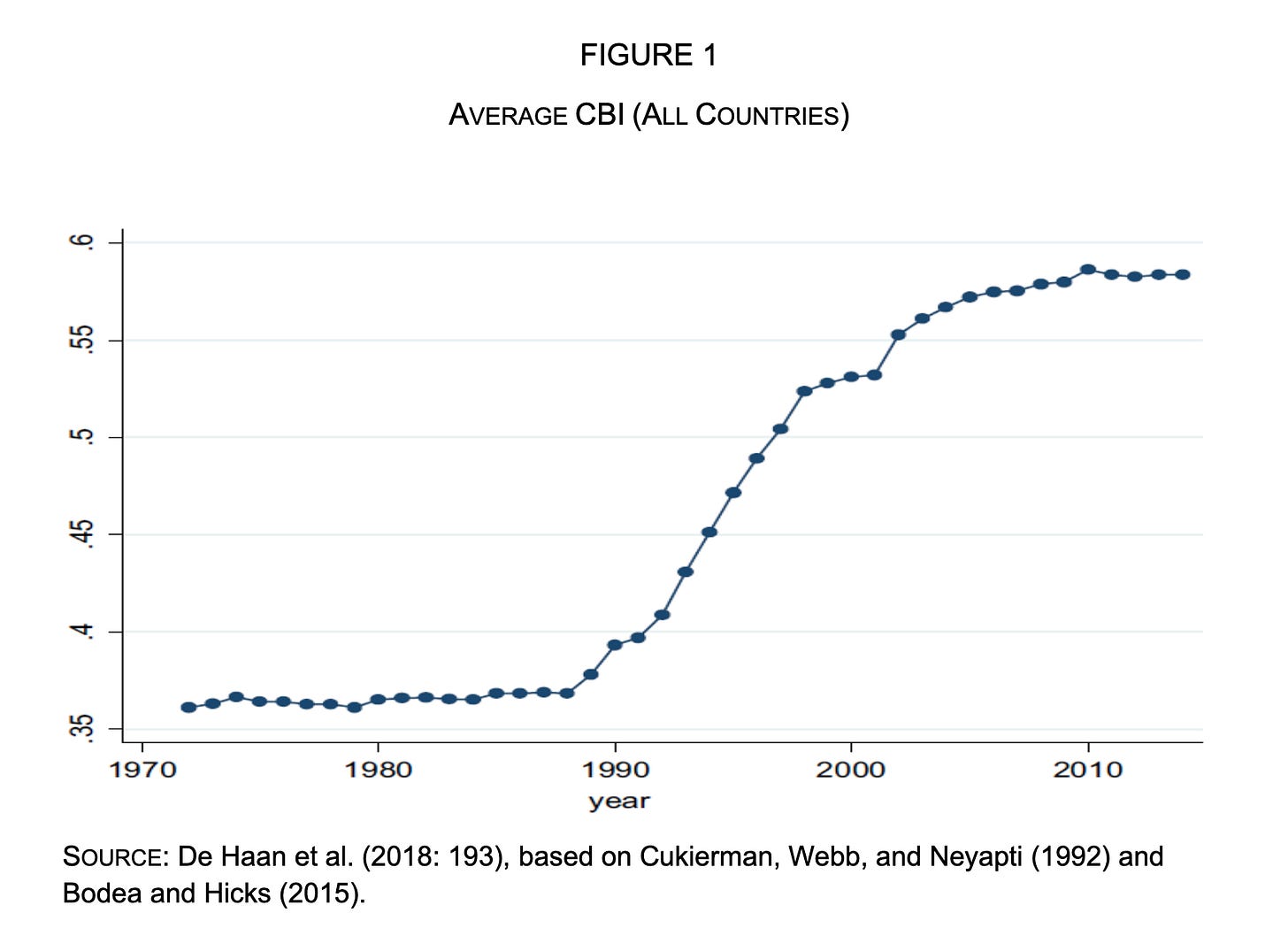

After a series of inflationary calamities in the 1970s, the notion of independent central banks caught fire around the world. The idea was straightforward: if you take monetary policy out of the hands of power-hungry politicians, it will be insulated from short-term, self-interested manipulation and will lead to more economic stability. The below chart shows the rise of central bank independence (CBI) over time, with a marked surge from the 1990s onward.

The results, according to most economists, have been largely positive—particularly so in the developing world. In countries with weaker economic management and more political volatility, independent central banking didn’t just improve monetary policy; it also improved the overall quality of governance by acting as a precursor to credible commitment. After all, if the central bank was truly independent, investors could have greater confidence than before that decisions would be based off of economic conditions, not political incentives. And that paved the way for other more empowering constraints on the passions of executive power.

However, the financial crisis of 2008-9 put independent central banks in advanced democracies back in the political crosshairs. There are legitimate critiques of the ways in which insulating such an important part of economic decision-making away from elected officials and voters can prove counterproductive, or simply end up making the rich much richer. Unelected central bankers, seemingly acting on narrow questions of monetary policy, inevitably make lasting distributional choices, creating winners and losers.

As Paul Wachtel and Mario Blejer argue, central banks engaging in crisis management during the Great Recession ended up rewarding the wrong people through their attempts to stabilize the economy:

By making massive purchases of government bonds, quantitative easing has held both short-and long-term interest rates low for a very long time. While this may have helped to stimulate declining economies, it has done so by making rich owners of financial assets richer still. At the same time poorer savers relying on bank deposits have been getting next to nothing.

Getting central bank independence right, therefore, is a tricky balance—and some economists argue that too much insulation from political pressure without appropriate transparency and accountability can be dangerous.

However, what literally everyone agrees is that central bank independence should not be challenged simply because a president or prime minister wants a more docile ally in charge, one who will do the bidding of the person in the palace—or the White House.

III: Cautionary tales from Orban to Erdogan

We know what happens when despots creep into central banking. For example, in 2011, Steve Bannon’s biggest crush—Hungary’s authoritarian strongman president, Viktor Orban—pushed for a constitutional change that weakened the central bank’s independence. Hungary’s credit rating was soon downgraded to junk status. The currency has since lost significant value.

Turkey’s authoritarian strongman, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, has gone even further. As the economist Rebecca Patterson notes:

Mr. Erdogan fired the central bank’s governor (who had kept rates high to slow inflation) and selected his replacement. Over the next few years, he continued to fire and replace governors and deputy governors.

Not much good came from lower interest rates. Since the 2018 election, the Turkish lira has lost 88 percent of its value against the dollar, according to Bloomberg data. Only the Argentine peso fared worse among emerging currencies during that period.

The central bank’s rate cuts and the weaker currency pushed up consumer price inflation, which peaked at an annual rate of more than 85 percent in 2022 and forced a sharp cycle of rate increases.

When presidents and prime ministers seek to remove the shackles of good governance that constrain them, it can bring a country past a point of no return, in which investors and economic players start to doubt the previous credibility of the underlying system. It takes decades for countries to build reputations for good governance, but those hard fought reputations can be destroyed in a single catastrophically consequential post on Truth Social.

As with so many news stories, then, Trump’s desire to fire Powell is being covered by America’s domestic press through the wrong lens.

This isn’t a story of Republicans and Democrats, or even a story of Trump vs. the Fed. This is a story of why functioning democratic institutions aren’t just aspirational ideals that sound good on paper; they provide the very foundation of lasting prosperity. And Trump’s temptation to fire Powell—to again follow his inner sirens of megalomania—is the latest chapter in a tragic saga, about the perils of America’s ongoing descent into authoritarianism, cheered on by disciples wearing wine-dark hats.

Thank you for reading The Garden of Forking Paths. This edition was free for everyone, but if you’d like to support my writing and research, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription for the low, low price of just $4/month. It makes my work sustainable so I can keep writing for you, as I rely exclusively on reader support. Alternatively, check out my book: FLUKE.

Other early key thinkers in this domain are Thomas Schelling and Robert Strotz. Elster’s formal definition of precommitment was “to bind oneself is to carry out a certain decision at time t1 in order to increase the probability of another decision being carried out at time t2.”

In advanced economies, credible commitment makes it possible for strangers to take calculated risks and engage in high-stakes transactions knowing that the government will enforce the agreement if one of the parties behaves unscrupulously.

The Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto argued that one of the most important constraints on governments was the creation of enforceable property rights to spark development in poorer countries.

The former radio DJ is still the president of Madagascar.

This is known as the time-inconsistency problem in economics. How can anyone be sure that what someone promises now will be what they also want to do in the future? Preferences change constantly. Precommitment and credible commitment are necessary to overcome that problem, making sure that everyone has confidence that a promise will be kept. However, too much commitment that locks governments into future action—even if the evidence changes or a better option arises—can be both undemocratic and damaging to governance and prosperity. Like all things in life, it’s about striking the right balance.