Is social media just...boring now?

Social media is destroying democracy and accelerating idiocracy. But it's also just...really, really boring.

Thank you for reading The Garden of Forking Paths. This edition is free, but if you’d like to support my work and keep my research and writing sustainable, please consider upgrading. It’s only $50 for a year ($4/month) and it also gives you full access to 215+ essays in the archive. Every bit helps.

I: The wisdom of sea squirts

One of humanity’s distant ancestors—though one that’s unlikely to show up at your next family reunion—are the tunicates, also known as sea squirts. In their early stage of life, they are active, little tadpole-like explorers, propelling themselves through their marine world.

As the creature matures, however, that free-spirited life gives way to a sedentary one, in which the sea squirt attaches itself to a suitable rock. It will never move again. Its body becomes little more than a passive sack, no longer searching or exploring, just waiting to see what drifts by, day in, and day out, for the rest of its life.

This is, as you might imagine, not a particularly intellectually demanding lifestyle. The sea squirt’s brain therefore becomes superfluous, an unnecessary waste of energy.

So, it does the logical thing: it eats its own brain, and gets on with surviving on whatever floats past.1 Even without a full brain, evolution has given the sea squirt the wisdom to realize when something no longer serves a purpose.

Many humans, by contrast, now mimic the sea squirt’s lifestyle on social media, but have not yet recognized an unfortunate truth: that their brains have become superfluous.

II: Origins

When I was 18 years old, I joined TheFacebook.com, one of the earliest attempts by a humanoid creature known as Mark Zuckerberg to socially fit in.

TheFacebook emerged after Zuck’s first creation, FaceMash, in which he hacked into Harvard’s databases—”child’s play,” he boasted at the time—and then subjected unknowing young women to being digitally judged by their peers, adjudicating who was hotter.

In written comments at the time, Zuck, clearly a chiseled supermodel himself, noted how ugly some of them were, saying “I almost want to put some of these faces next to pictures of farm animals and have people vote on which is more attractive.” (Perhaps we should rethink a society in which this creature is one of the richest and most powerful lifeforms on the planet.)

After backlash to FaceMash grew and he took the site offline, Zuckerberg, in his first—but certainly not last—inauthentic apology wrote: “I’m not willing to risk insulting anyone.”

When I joined TheFacebook in 2004, there were around 50,000 users globally. It was only open to students at a smattering of elite colleges and universities. It was a gigantic, unknown social experiment, the first frontier of a new way of connecting to people.

It was exciting.

But nobody had a clue what to do with it. Beyond “friending” someone—a bold step, to be sure—one could also create groups. This lent itself to playful experimentation.

At my college, there was a relatively ordinary student named Luke Nobel-Plimpton (names have been slightly modified to protect the victim). His friends, recognizing an excellent prank opportunity, created a closed Facebook group called “People Who Are Not Luke Nobel-Plimpton.” The group’s membership criterion was singular—and ruthlessly enforced.

Soon, the group spread like wildfire. On a campus of 2,000 students, the group’s ranks swelled to nearly 1,700. Luke Nobel-Plimpton became a campus celebrity; spottings in the wild were celebrated at parties in drunken whispers.

Then, there was the “poke” feature. (Humanoid Zuckerberg acknowledged that he came up with the idea while his carbon-based body was intoxicated.) Nobody knew what to do with it, but it could be tremendously exhilarating when that little notification arrived from someone who was not a close friend. On the flip side, after an impulsive moment, many a student also experienced a novel feature of the human condition unknown to Dickens or Dostoevsky: poke regret.

But TheFacebook in 2004 was also radically different to social media today. In short, it was better, safer, healthier, more interesting, and more human. Why?

First, it was a closed network: you were only exposed to posts from people you were friends with, nobody else. If you got exposed to insane opinions, that was only because your real-world friends were insane. And because everyone knew they were posting for their actual friends, people with secretly insane opinions tended to keep them to themselves, lest they be socially shunned.

Second, there was no algorithm, stuff just showed up as it was posted, without any rewards for posts or photos that were clickbait. There was therefore no premium on attracting eyeballs. Blissfully, there were no influencers (aside from obscure legends like Luke Nobel-Plimpton).

Third, early social media fostered rather than replaced real-world connections. The main reason to join TheFacebook in 2004 was to figure out what parties were happening, when people were meeting up, and what activities were happening on campus. It was therefore a catalyst for social activity; today, it’s a catalyst for loneliness, built to reward the dystopian act of scrolling alone.

Fourth, if you were an insufferable, bad-faith jerk, you tended to lose friends, not gain followers. (I’ve written about the perils of audience capture here, but the current model is particularly toxic for rewarding ratcheting extremism).

In 2025, we’ve gone so far through the looking glass that, as Derek Thompson recently highlighted, Meta filed a brief in an antitrust case with the Federal Trade Commission officially arguing that it could not possibly be considered a social media monopoly because it is not even in the business of social media. Here’s what they wrote in their brief:

Today, only a fraction of time spent on Meta’s services—7% on Instagram, 17% on Facebook—involves consuming content from online “friends” (“friend sharing”). A majority of time spent on both apps is watching videos, increasingly short-form videos that are “unconnected”—i.e., not from a friend or followed account—and recommended by AI-powered algorithms Meta developed as a direct competitive response to TikTok’s rise, which stalled Meta’s growth.

In other words, “social” media apps are no longer remotely driven by real-world interactions; they’re just people watching short-form videos and, at best, occasionally interacting with other humans (and, increasingly, with AI bots) in the comments.

We have totally lost the plot.

III: Why do people spend so much time on something that’s so mind-numbingly boring?

The problems of modern social media are well-documented. At its worst, it polarizes people, destroys social trust, amplifies stereotypes, encourages real-world violence, mainstreams extremism, gives hateful politicians direct-to-voter megaphones, makes the world’s most insufferable people rich and famous, splinters a shared sense of reality and, ah yes, helps destroy democracy. (On the other hand, it also has amusing dance videos.)2

For a while, I was a heavy user—particularly on pre-Muskian Twitter. It was too much. I regret how much time I wasted on the site. I now don’t have any social media apps on my phone and I check social media far less often.

But the more I’ve thought about why I’ve made that switch, I’ve realized that my personal aversion to social media has emerged from a more fundamental reaction to it: utter boredom.

As a little experiment, I visited X yesterday, for the first time in a very long time. In order, the feed offered me:

An Elon Musk post comparing any transgender health care to Josef Mengele, who happily oversaw the gas chambers at Birkenau and Auschwitz;

A video of a woman inexplicably smashing a man’s car windshield with a hammer;

A video of a man suffering terribly as an amusement ride malfunctioned, much to the amusement of gleeful monsters in the comments;

Sam Altman posting about how ChatGPT will now be much better because the new version will “respond in a very human-like way, or use a ton of emoji, or act like a friend” alongside an announcement that ChatGPT will soon produce erotica on demand.

Please, just unplug it.

It’s vile, obviously, but it’s also just so predictably boring. The same stuff every day, churned out by the same eyeball chasers, amplified by many of the most loathsome people on the planet, day after day after day.

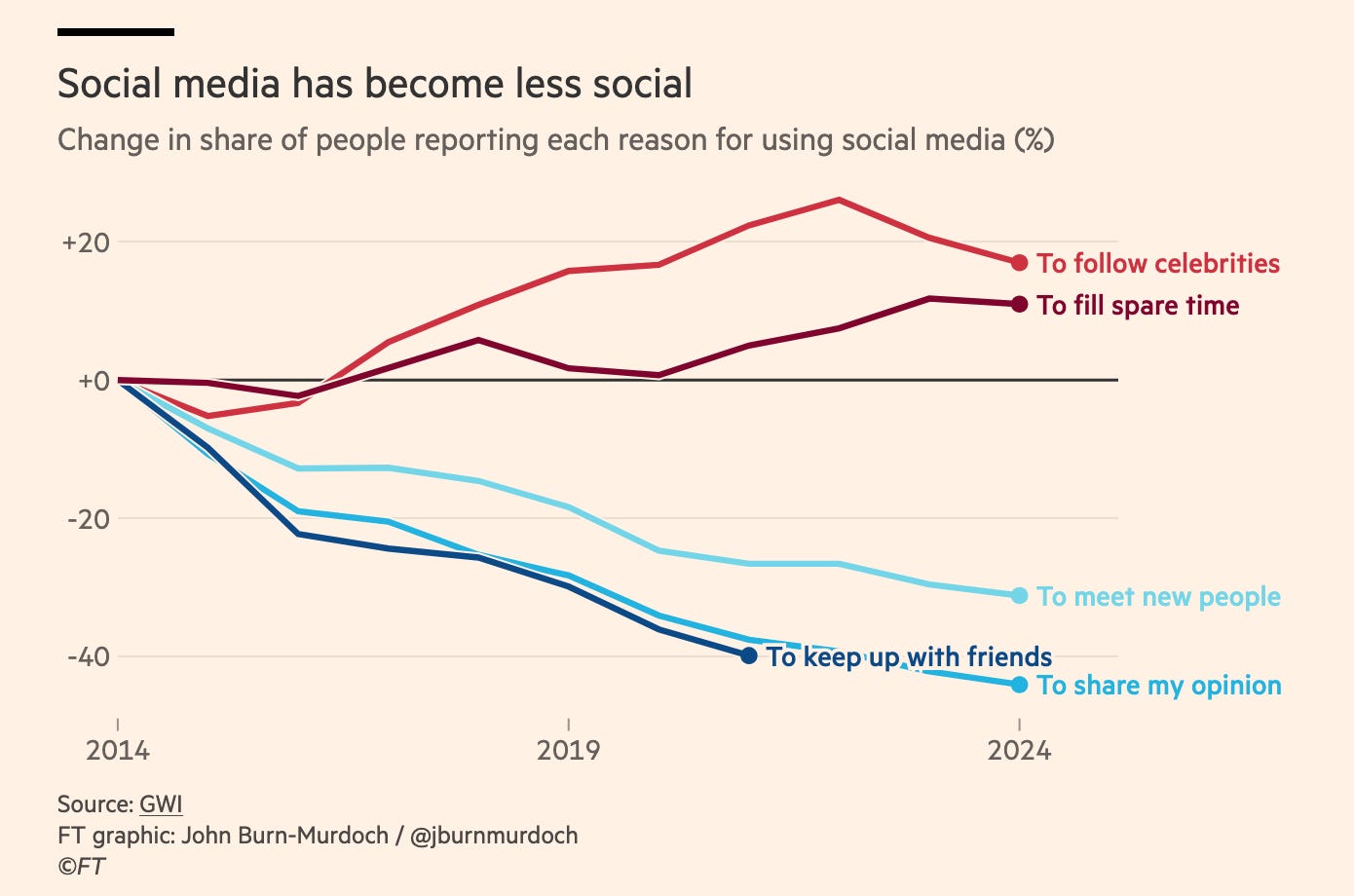

John Burn-Murdoch, data guru for The Financial Times, has produced an extraordinary chart, showcasing how much of social media today is just tedious, pointless scrolling, watching “content” (from people I would swiftly run away from if I encountered them at a real-life party). The biggest growth areas are unabashedly mind-numbing: “to follow celebrities” and “to fill spare time.” At that point, why not just take a page from the sea squirt playbook and eat your own brain?

Thirteen billion years ago, an improbable universe inexplicably blinked into existence. Life on Earth arose 3.8 billion years ago. And over the ensuing aeons, countless single-celled organisms lived and died, the slow march of evolution later conjuring trilobites and dinosaurs, down the line to chimpanzees and other non-human primates, eventually leading, through infinite accidents and flukes of history, to one species with advanced cognition, extraordinary self-aware consciousness, and an unbridled capacity to experience joy, to gain knowledge and wisdom locked off to all other species, to invent, explore, connect, learn, and to love.

Within that species, there are an infinite number of possible people who could have existed but do not, the unborn ghosts, the sparks of life that never were, and from that infinite realm of possibility, we are the few lucky ones.

And lucky we are, though for most of us, our luck runs out after around 30,000 days on the planet. Precisely how many of those impossibly lucky days of our improbable existence are well-spent filling spare time by following the vapid lives of celebrities?

IV: It’s better to not eat your own brain

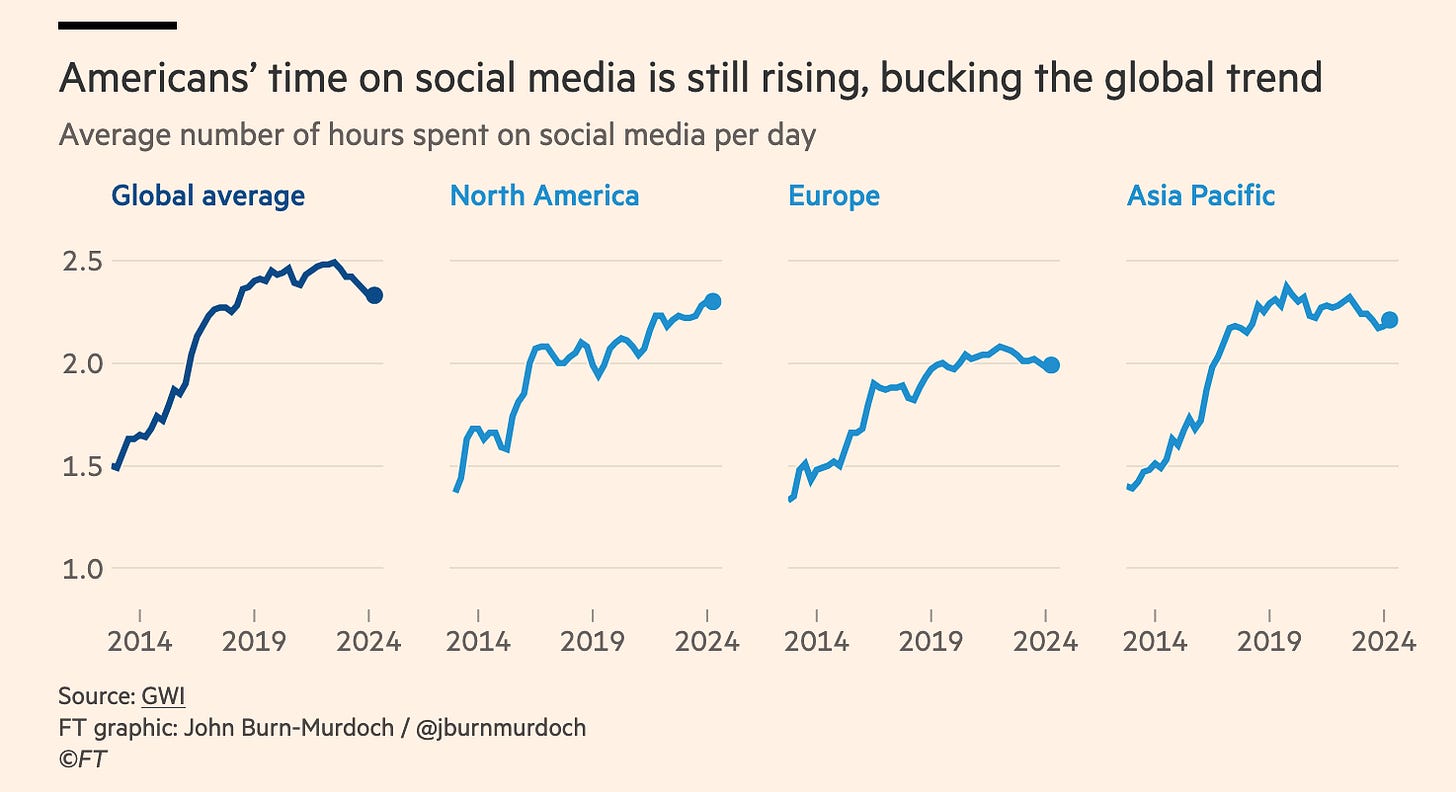

Thankfully, some people are wising up to the perils of sea squirt lifestyles. For the first time, social media use is declining globally. But there’s one exception: in North America, it’s still going up, as John Burn-Murdoch again shows:

The global numbers reflect a growing sense I feel when I talk to others: that many now see social media in increasingly negative terms, not just as a corrosive social phenomenon but as a personal blight on their life. To some, it feels like a chore; to others, an addiction they can’t break even though they desperately want to leave it behind.

My suggestion is this: next time you log onto a social media platform, use two tests to evaluate whether it was worth it:

The Sea Squirt Test: Did you need to use your brain?

The Social Test: Did you feel genuine human connection?

If neither test is passed, obliterate that platform from your life. You only live around 30,000 days; today is one of them, and the world is far too fascinating a place to waste any more of them on something so destructively boring.

Thank you for reading The Garden of Forking Paths. If you value my writing and research, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription for $50/year or $4/month. It makes my work sustainable—and you can be a modern Medici, fashioning yourself as a patron of the human creative arts in an era of increasing glittering sludge spewed out by artificial intelligence.

This story is somewhat simplified, as sea squirts still have brains in adulthood, and their behavior and physiology is well-adapted to their strategy for survival. In the larval stage, it’s swimming around with a tail; in the adult stage, it’s becoming a passive feeder. Astonishingly, their hearts do something profoundly weird: every three or four minutes, they reverse the direction of blood flow. They are the only animal known to do this. Here’s a review article on their physiology.

The Washington Post did an interesting experiment, tracking 1,100 people in their TikTok use over a year. The results are really depressing—and they showcase how some of the phenomenon functions as a genuine addiction. Their report is worth reading.