Gerrymander to Save American Democracy

Yes, I know it sounds crazy. But a specific type of gerrymandering—to boost competition—is the best hope for saving a broken system that's lurching toward authoritarian rule.

Thank you for reading The Garden of Forking Paths. If you’d like to support my work, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription. It makes the newsletter sustainable.

Imagine a system of “democracy” where elections are so lopsided, so uncompetitive that elected officials usually win in a landslide. It’s rarely a fair fight. Nine times out of ten, incumbents win. The election is a foregone conclusion before the ballots are even printed.

You don’t need much of an imagination. This is the reality for many notoriously undemocratic elections in sub-Saharan Africa.

But it’s also the reality for the United States Congress.

In 2016, guess what proportion of incumbents from the House of Representatives were re-elected? The answer is shocking: 96.7 percent. When incumbents ran for re-election, they only lost about 3 out of every 100 times.

Over the last twenty years, on average, sub-Saharan African presidents and members of the US House of Representatives have won elections by roughly the same landslide margins of victory: 33 percent.

The approval ratings for Congress are dismal. We love to hate Congress, but we rarely replace its members.

What’s going on?

How to Fix American Democracy

I’m often asked some version of this question: how can we fix American democracy?

There are a million possible answers. The Supreme Court needs to be reformed. The role of money in politics is out of control. Primaries are completely broken. The Senate is increasingly out of step with public opinion, because just under 70 percent of the country controls only 30 percent of the seats. The Electoral College is a relic of a bygone age, yielding the embarrassment that you can get more votes and still lose.

But if I had to pick one, I’d pick this: fixing gerrymandering.

However, I’m going to surprise you now.

I think we need more gerrymandering, and I think we need to do it deliberately—in an open, systematic way. Once I explain what I mean, I suspect many of you will see the logic of my argument and realize that, in the current political environment, it may just be the closest thing we’ve got to a silver bullet that could fix American democracy.

Rigged by Design

It seems strange to think of America’s elections as rigged. Yet, Congressional elections regularly feature Kim-Jong Un-style margins of victory. Speaker of the House John Boehner won re-election in 2012 with a margin of 98.4%.

This isn’t really an outlier; in roughly one of every four Congressional races, the incumbent wins by more than 50%; in about two out of three, the margin of victory is greater than 20%.

In 2022, Danny K. Davis, who represents the Illinois 7th Congressional District, received 99.94 votes. He got 167,650 votes. The runner-up, a write-in, got 96 votes.

In those same midterms, just 40 out of 435 House seats had a margin of victory within 5 percentage points. That means that 91 percent of House elections weren’t even close.

As we’ll see, that uncompetitive dynamic poisons democracy—far beyond when the votes are counted.

What is Gerrymandering?

The simplest definition of gerrymandering is the most elegant:

Gerrymandering is when politicians pick their voters rather than voters picking their politicians.

But the origin story of the term is worth telling. When you think of election rigging, you probably don’t think of salamanders. But you should.

Elbridge Gerry was, according to his biographer, “a nervous, birdlike little person” who, was prone to a peculiar, constant, “contracting and expanding the muscles of his eye.” But he was also one of America’s Founding Fathers, one of the first governors of Massachusetts, and the Vice President of the United States during the presidency of James Madison.

His legacy lives on, sadly and ironically, due to a practice that he opposed.

Gerry was governor of Massachusetts in 1812 when his own political party, the Democratic-Republicans, redrew electoral districts to their own political benefit. As Erick Trickey (who better to write about gerrymandering with a name like that?) explains:

Until then, senatorial districts had followed county boundaries. The new Senate map was so filled with unnatural shapes, Federalists denounced them as “carvings and manglings.”

Gerry signed the redistricting bill in February 1812 – reluctantly, if his son-in-law and first biographer, James T. Austin, is to be believed. “To the governour the project of this law was exceedingly disagreeable,” Austin wrote in The Life of Elbridge Gerry in 1829. “He urged to his friends strong arguments against its policy as well as its effects. … He hesitated to give it his signature, and meditated to return it to the legislature with his objections.”

But Gerry eventually signed it, because in those days, the only grounds not to do so was if the bill was deemed contrary to the Constitution, rather than just being distasteful.

This gave rise to the political cartoon that provides the art for this article, a monster comprised of the bizarre shapes that became the skewed electoral districts. According to an 1892 account, the term “gerrymander” was both drawn and coined at a dinner party. One guest noted that the drawing looked like a salamander. Another retorted: “No, a Gerry-mander.”

The name stuck, though we pronounce it incorrectly. Elbridge Gerry was pronounced the way that we say “Gary” today, so the original pronunciation would have been “Gary-mander,” though over the centuries, it has morphed into “Jerry-mander.”

Gerry died a few years later—while he was the sitting vice president—when he went to visit a Treasury official. This is the official account of his death, from a letter to John Adams:

[Gerry] went in his carriage to call upon Mr. Nourse of the Treasury Department, complained while there of feeling unwell, was helped by Mr. Nourse into the carriage to return to his Quarters, distant not more than a quarter of a mile, was senseless when he arrived there, and on being taken out, and laid upon a Bed, immediately expired without a Groan or a Struggle.

(I wish we still wrote like that—and I hope to expire with neither Groan nor Struggle).

Why Partisan Gerrymandering is So Toxic to Democracy

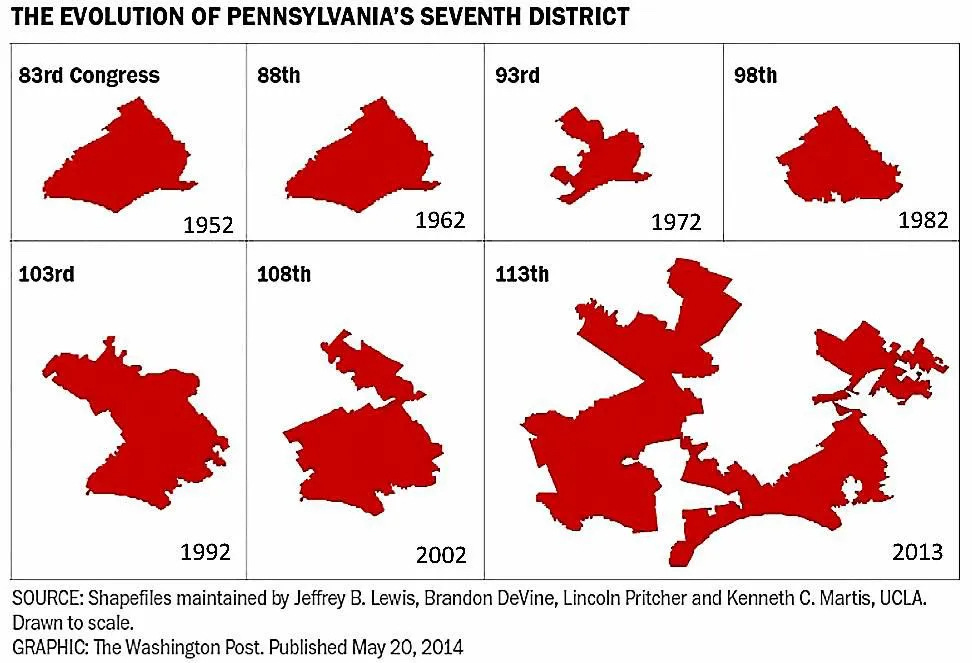

Take a look at the evolution of Pennsylvania’s 7th District over time (image from The Washington Post, via researchers at UCLA).

Up until recently, when the district was finally redrawn, the district was known as “Goofy Kicking Donald Duck,” because that’s what it looks like. See, in context:

Now, there are times when absurdly drawn districts are contorted for more defensible reasons. For example, in accordance with the Voting Rights Act, there are efforts to try to ensure that minority communities have more representation in Congress. That has led to districts like the Illinois 4th Congressional District, which has sometimes been called “Latin Earmuffs,” for reasons explained in this New York Times graphic, using data from Jeffrey Lewis, Brandon DeVine, Lincoln Pitcher, and Kenneth Martis:

Moreover, gerrymandering is only part of the problem when it comes to noncompetitive elections. There’s also a phenomenon known as demographic sorting, in which like-minded people tend to live near each other.

It’s a chicken or egg problem. If you grow up in rural Alabama, you’re far more likely to end up as a Republican voter. But if you’re a rare far-right voter who’s living in, say, Portland, Oregon (a Democratic stronghold), you’re more likely to find the prospect of moving to a red state more appealing. Over time, then, there can be ratcheting effects where Republican areas get more Republican and Democratic areas get more Democratic.

The upshot is this: Gerrymandering + Demographic Sorting = Landslide Elections.

Why does that matter? The answer that most people identify is the wrong one, in my view. To most people, gerrymandering is bad because it’s unfair and creates partisan skews. Of course, that’s true. But it’s less bad than you think, because both parties—to some extent—are guilty of gerrymandering. That means that, as a recent study at Harvard found, some of the gerrymandering cancels itself out, somewhat reducing the partisan bias in Congress.

But there’s a much bigger problem.

Democracy is founded on competition. The logic of democracy is that politicians and political parties will compete for votes, which will ensure government responsiveness. But once the competition goes, democracy starts to fail and break apart, because the mechanism that creates responsiveness has disappeared. If you can’t vote someone out, how do you create democratic accountability? The answer is: you can’t. That leads to the following fact, which is incredibly disturbing:

America has engineered an electoral system that undercuts the core principle of democracy.

How has that happened? Well, in 2016, the average margin of victory in elections for the US House of Representatives was 36.6 percent. That means that the standard election was roughly a 68 percent to 32 percent landslide.

Put yourself in the shoes of a politician in that “normal” district. Let’s say, for the sake of argument, that it’s a Republican district, where 7 out of 10 voters vote for any Republican on the ballot and Trump has a 70 percent approval rating within the district. What incentives do you face?

If you always praise Trump, no matter what, then you’ll get re-elected in a landslide. As a loyal Republican foot soldier, it’s impossible to lose in your gerrymandered district. On the other hand, if you criticize Trump even once, then you’re likely to trigger a primary challenger. (I’ve written about how primaries might be reformed here).

Here’s the problem: primaries are low turnout contests, in which the diehard extremists vote most often—and therefore form a high proportion of the primary electorate. So, whoever captures the GOP extremists (or, to use the more politically acceptable term, the MAGA “base”) will win the primary. It leads to this calculation:

Never Compromise + Always Praise Trump = Easy Re-Election

Compromise OR Critique Trump = Guaranteed Primary and Lose Job

That creates the crucial bottom line:

In noncompetitive districts, politicians aren’t responsive to the electorate, but instead are responsive to the extremists.

Over time, those dynamics are corrosive to democracy, because they warp the incentives politicians face, but they also warp the political party—which is what happened to the Republicans since 2016. As the MAGA base became more rapidly and uncompromisingly pro-Trump, every aspiring Republican candidate has understood clearly that they needed to become a Trump disciple to keep their job. (See how Elise Stefanik, for example, transformed almost overnight).

In thinking about this over the last seven years, that toxic political reality has led me to the following conclusion:

If American democracy is going to be saved, we first need more competitive elections.

To Save Democracy, Draw More Competition

When people think about gerrymandering, they normally picture weirdly contorted districts. But why is a square better than a squiggly line? There’s nothing magically democratic about a square shape. Sure, these days, squiggly lines are often clues that someone is manipulating a district map for partisan gain. But the solution to this isn’t just to partition the United States up into squares and call it a job well done. After all, we don’t live according to squares, so why should our districts be that way?

Every electoral map—no matter who draws it—is biased in some way. It’s literally impossible to draw an unbiased map. Minnesota, where I’m from, has eight districts. How can you possibly partition the state in a way that everyone agrees on? Should Minneapolis have its own district? If so, why? If you have a rectangle, should it be longer north/south or east/west? Why?

These are ultimately somewhat arbitrary choices. Even if we had nonpartisan districting that was trying to be fair (we currently don’t in most states), the maps drawn by those commissions would still produce mostly noncompetitive elections due to demographic sorting. How do you draw a competitive map in the deep blue stronghold of Portland, Oregon? It wouldn’t solve the real problem, which is a lack of competition in American politics.

What if we flipped the logic of gerrymandering on its head? Instead of trying to draw unbiased maps—which is impossible—let’s choose the bias that we want.

My proposal would be to aggressively gerrymander in order to maximize competition.

In other words, subdivide the United States into 435 House districts that maximize the number of districts that are likely to have swing elections. Right now, that number is typically less than 50 out of 435. It would be relatively easy to use creative districting to boost that number to somewhere between 150 and 250.

In some places, enacting my proposal would be impossible. Wyoming, which has one district for the entire state, will probably never be competitive.

But it would be possible to deal with America’s overly polarized rural/urban divide more effectively, by drawing some districts a bit like a slice of pizza with the tip entering a city and the crust going out into the sparsely populated farmland, so that the elected member of Congress has to represent some rural, some suburban, and some urban voters. Crucially, they would have to respond to everyone, not just the extremists, because they’d face a credible threat of losing the general election if they didn’t.

Getting this reform passed would be difficult, I admit, because incumbents don’t want competition. They want to sail to re-election. But through ballot initiatives and other citizen-led efforts, we could enact change, state by state and district by district. And the first step is articulating a vision of what we should aim for: competitive elections.

There are tradeoffs to any system, and these would have to be thought through carefully. For example, minority representation is important, so you would want to ensure that any proposal wouldn’t undercut ethnic diversity in Congress. And you’d still want some solid blue or solid red districts, as Democrats and Republicans alike probably want to retain some of their hyper-progressive or hyper-conservative champions.

But after lots of chin scratching about the systemic roots of America’s lurch toward authoritarianism in the Trump years, I’m convinced that many of the proposed reforms to America’s broken system are window dressing if we don’t restore the founding principle of democracy: competition.

Thank you for reading The Garden of Forking Paths. If you found this interesting or thought-provoking and you think I should be paid for my research and writing, please consider upgrading to support my work. I rely exclusively on reader support. And please do share this widely, so I the newsletter can continue to grow.

Brian, you are right. The very heart of democracy is competition! But you neglect the real punchline about what that competition is over. Ideally parties and candidates compete over ideas of how government should serve the people, and what would enhance society overall. But in the US, we have a poorly educated electorate overall for whom religion and superstition and conspiracy theories pass as enlightened thinking for a substantial number, though not all. As a consequence the “competition of ideas” is really about how to force religion and lifestyles and thinking upon anybody who prays, lives, or thinks differently from the dominant Protestant evangelical orthodoxy that is backward looking to the old days. It is a cultural of fear and superstition. It is a culture of wanting to keep a privileged position in society not based on merit or hard work, but simply as birthright by the color of one’s skin or practice of dominant religion. This is the antithesis of the openness, exploration, discovery, and advancement that comes from a true competition of ideas.

With all that said, maybe drawing up districts that have close to even split between D/R representation can work, but what of registered independents? They come all across the political spectrum. And then this does nothing to solve the (US) senate problem. And what if increasingly active voter suppression?

I am happy you are writing about this. It needs to be discussed and real change needs to be on the table. But I fear for US democracy and governance.

There is so much to think about here! I was a poli sci major, and I was taught that we need to keep groups of interest together, which I thought would help racial and ethnic groups have a chance at getting representation. But I 100% agree that competition would greatly help our federal government and our country. And any improvement would be wonderful.

I'm like Zach- a liberal in a red state, without representation that actually represents me (even on the state level). Pizza cutting would help liberals like me in the suburbs for sure. But I'll need to think through the states I'm familiar with and see if it would help the folks living in the blue cities who'd be losing their only sure representation, or if it would help the ethnic groups that live together (Indian tribes or towns like Dearborn, MI for example). I wouldn't want majority rule to wipe out their chances to be heard. Then of course, any better ideas for redistricting have to actually get implemented, which would take a miracle. At any rate, I really wish you taught a class online or something so I could ask all my many questions. :)