How to Fix the US Supreme Court

America has a Supreme Court problem. Here's what the United States can learn from two island nations, Comoros and Fiji, about how to solve it with consociationalism and centripetalism.

Thank you for reading The Garden of Forking Paths. This article is free, but I’m trying to devote more time to researching the newsletter, which requires revenue to “buy out” some of my other commitments. To support my work so I can devote more time to writing for you (and to get access to more articles!), please consider upgrading to a paid subscription.

“The reasonable man adapts himself to the world: the unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore all progress depends on the unreasonable man.” So said George Bernard Shaw. And in this edition, I present myself as an unreasonable man, unwilling to accept the status quo of an extremist court that is taking a wrecking ball to important pillars of American life.

But most current discussion about reforming the court revolves around band-aid solutions and stopgap measures. To learn how to properly fix the court, we’ll need to learn lessons from two tiny island nations: Comoros and Fiji.

Ideologues in robes

The United States Supreme Court is a politicized institution masquerading as an impartial one. Over time, legal principles have been subsumed into a court dominated by ideologues. Modern justices are selected as much for their partisanship as their age.

Donald Trump’s three appointments were all younger than average. Amy Coney Barrett was appointed at 48; Brett Kavanaugh at 53; Neil Gorsuch at 49.

It’s a cliché, but a true one, to say that elections matter. If Hillary Clinton had won in 2016, it’s likely that there would be a 6-3 left-wing majority on the court for a generation rather than 6-3 right-wing one. But because of lifetime appointments and the relatively young age of the current court, it’s likely that Republicans will dominate the US Supreme Court for up to a quarter century.

That has created an unsustainable dynamic—in which unelected judges, appointed for a lifetime, by a president who received fewer votes than his opponent, confirmed by a Senate in which roughly 70 percent of the population controls about 30 percent of the seats—are reshaping crucial areas of American law against the wishes of an overwhelming majority.

For example, the court struck down Roe v. Wade last summer, even though just 37 percent of Americans think that abortion should be illegal. This is likely just the beginning, of a period in which the court transforms American life with radical minority viewpoints that touch everyone, even the apolitical and the apathetic.

This is different, by the way, from the Warren Court, which is sometimes described as the most liberal, rights-expanding court in US history. Rulings like Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which mandated de-segregation of American schools, were not just rights-expanding, they were also largely supported by the population. (Here’s polling data about Brown v. Board, drawn from this research article).

Today, the court is creating policy that is broadly opposed by the public. Because of how the court works, insulated from majoritarian opinion and likely to linger on for decades, it’s dawning on Democrats that presidential and Congressional authority won’t be enough. They can win elections and pass laws, only to have them struck down by six people in black robes, many of whom are extremists badly out of step with public opinion.

Of course, that’s how American democracy has long functioned to a certain extent, but this is different because modern polarization is off the charts and the court is consistently ruling for a diminishing minority that is highly unrepresentative of the country. (Some of the right-wing justices also seem to be rather fond with cavorting with billionaires who have vested interests in cases before the court).

Jettisoning democracy’s safety valve

However, most partisan shouting about the court has failed to focus on a crucial dynamic that, in my view, should define the debate: the loss of competition and the hopelessness of unchanging political power.

The foundation of democracy is competition. In divided societies, competitive elections act like a safety valve, providing the opposition realistic hope that they could soon be in power. At the national level, Democrats and Republicans get a shot at meaningful political control every two years, with midterm or presidential elections. Persuade voters, take power.

The Supreme Court is different. It’s now entrenched rule of minority viewpoints. Under the current system, even if Democrats won 100 percent of votes in the 2024 elections, they would still be stuck with a 6-3 conservative majority in the Supreme Court for the foreseeable future, most likely at least fifteen to twenty years.

But getting rid of democracy’s safety valve—by solidifying long-lasting political control with no hope for change—can end badly. To find out how, we must turn to the most unexpected place: three forgotten islands in the middle of nowhere. Learning from them, we can find a fresh roadmap for the best ways to reform the US Supreme Court, which don’t rely on just expanding the court.

Consociationalism and the “Coup-Coup” Comoros Islands

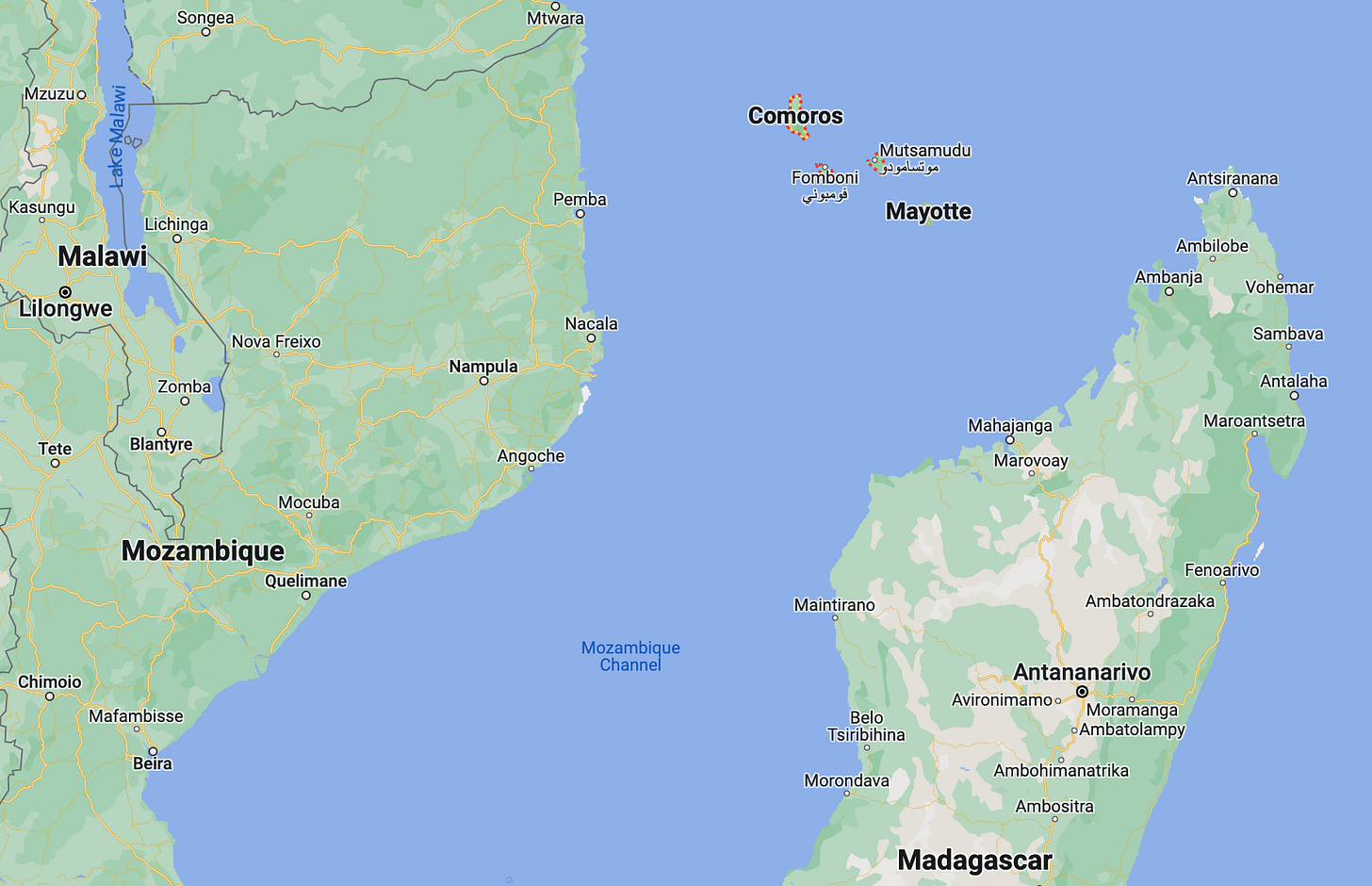

I’ll forgive you if you’ve never heard of Comoros, as it’s a tiny island nation off the coast of Mozambique and Madagascar in the Indian Ocean, home to just 850,000 people. By land area, Rhode Island is twice its size.

Comoros has three main islands—Grande Comore, Mohéli, and Anjouan—and they are divided not just by the ocean, but by toxic politics. On average, someone attempts a coup d’état in Comoros every two years, which has given it the unfortunate nickname of the “coup-coup islands.”

For much of its recent history, Comoros has had four parallel governments—with four presidents and four parliaments—for 850,000 people. That’s because each island has had its own government complete with a president (now called governors), plus a national government, with its own president.

Here’s the intriguing bit: after a series of constitutional changes, the national presidency automatically rotated between the islands every five years. One island would govern for five years, then transfer power to the second island, then to the third island, then back to the first. The idea was that each island knew, with certainty, that it would be back in national power precisely ten years after leaving it.

This was a form of what political scientists call consociationalism, in which institutions are designed to foster elite consensus and avoid violent conflict. It’s a mechanism to engineer peace and compromise, rather than just hoping for it. After all, you won’t go after your rivals too much if you know they’re going to be back in power soon.

In Comoros, it sort of worked, though coup attempts persisted. It was a mixed bag because it was a half-way compromise. Yes, it guaranteed that everyone would have political power—something known as a power-sharing agreement. But it also guaranteed a long wait before returning to power.

The Comoros system created negative certainty for two of the three islands: that they would be out of power for ten years, no matter what happened, while they waited their turn. That guarantee of long-term powerlessness changes political dynamics, because it creates pressure on those denied power to change the system, to restore their hope of gaining control sooner. (It created an incentive for coup attempts, too).

The US Supreme Court now has all the bad aspects of the Comoros system with none of the good ones. Democrats now have negative certainty: they know the court will be controlled by Republican-appointed justices for much more than a decade (barring several unexpected deaths, illnesses, or retirements). But, unlike the Comoros system, they don’t have any guarantee that they will ever regain power.

It all depends on when the oldest justices retire or die. (Clarence Thomas, age 75, is currently the oldest). If Thomas and Chief Justice John Roberts leave during the tenure of a Republican president, right-wing control of the court—by judges who are increasingly out of step with the rest of the country—could feasibly last for three or four decades. Even for some Republicans, this is bad news, as not all GOP voters are as socially conservative as this court.

So, we’ve got a dose of Comoros in America, with negative certainty that Democrats will be out of judicial power for at least a decade. But to understand the next piece of the puzzle, we must consider another tiny island in the middle of a different ocean.

Centripetalism and the Lessons of Fiji

The distant cousin of consociationalism is known to political scientists as centripetalism. It refers to institutions that create centripetal forces, drawing politics toward the middle—and toward compromise. In dangerously divided societies, centripetalism can, in theory, stave off a return to political violence.

Consider a country with a history of political violence, like Fiji, where political divides are mostly ethnic, not ideological. It’s not that they disagree about a specific policy, but rather that they want to keep political control away from a rival ethnic group.

One solution tried in Fiji was to implement a form of ranked-choice voting, in which voters had to rank candidates, forcing them to consider which party/ethnic group beyond their own was “second best,” and “third best,” and so on. The idea was that political parties would only be able to win by appealing to other ethnic groups, not just their own, and that would lead to a politics geared toward compromise and consensus. If you engineer an institution that only works when rivals agree, it chips away at divisive politics. (This can work, and it’s a good idea in principle, but Fiji has had mixed results).

Now that we understand these differing models of contentious island politics—with their strengths and weaknesses—we can put these ideas together, and consider possible mechanisms to reform the US Supreme Court using consociationalism and centripetalism. If we’re going to properly fix it, we need to end a decades-long slide toward dysfunctional partisanship overseen by ideologues who play dress up in the bygone robes of principled nonpartisans.

How to fix the Supreme Court

As I’ve previously highlighted, we mostly debate ideas within the politics of the possible right now, which means we ignore the politics of the ideal—what we should strive to achieve. Yes, it’s difficult to imagine my proposed reforms happening in the current political climate. Some of these ideas would likely require Constitutional amendments. But it’s better to sketch out the best reforms, rather than proposing half measures. Aim for the ideal, even if we miss.

Many Democrats have become more vocal about their calls to expand the Supreme Court, simply adding more left-wing justices to the bench. This may be the most straightforward way of dealing with the lopsided negative certainty of this 6-3 right-wing court, but it doesn’t solve the underlying problem—and it would create new ones.

Even if Democrats could expand the court, the death spiral of a hyper-politicized judiciary would grow worse, because nothing would change about the appointments process. It would remain toxic, forever.

Moreover, once Republicans had the opportunity, they’d have every reason to expand the court even further, creating a ratcheting arms race of judicial changes, and the near-certainty of ever-more extreme, dysfunctional politics.

So, what would be the ideal solution?

First, reform judicial selection. Most countries select high court judges from a list curated by an independent, nonpartisan panel. They’re all highly qualified, vetted by those who care about the law, not ideology (this is a much better vetting process than Senate committee hearings, which are now largely meaningless charades geared toward getting Senators featured on cable news). The UK appointments system, for example, does a pretty good job of ensuring that the court doesn’t get overtly politicized.

Once the appointment system is fixed, and the court begins to slowly de-politicize, then it’s time to consider broader reforms, making it impossible for partisan zealots to maintain long stretches of unaccountable decision-making.

Here, I’ve been influenced by the ideas of David Orentlicher, a law professor at the University of Nevada—Las Vegas. He outlines a few viable options that would resolve the underlying issues, curing the disease rather than just temporarily alleviating the pain.

Option 1: The Consociational Model

Perhaps it’s time for power-sharing in deeply divided America. One possible outside-the-box solution would be to change the institution, through Constitutional reform, to mandate an even number of justices for each of the two main parties in Congress. This may sound outlandish to Americans, and it may seem foolhardy not to have an odd number of judges to break ties, but courts with even numbers of judges are more common than you might think.

As Orentlicher points out: “the constitutional courts in Germany and Spain have sixteen and twelve judges, respectively. Similarly, Austria's constitutional court has twenty judges, and Belgium's has twelve.” And the US Supreme Court has operated with a 4-4 split in the past, when a justice has retired or died. It worked just fine.

A similar proposal comes from a model closer to home. New Jersey has long had a system in which Democrats and Republicans get three of the seven state Supreme Court seats apiece, while the incumbent governor fills the final seat. There’s always a 4-3 majority tied to the governor’s party, which directly links control of the court to elections, ensuring that there is never that negative certainty about being out of power indefinitely. Plus, there’s never a lopsided margin—it’s always a closely divided court.

Judges therefore have a stronger incentive for thoughtful, consensus-based jurisprudence. Consequently, New Jersey’s Supreme Court is consistently one of the most influential state supreme courts in America. Perhaps we should just mandate that the pendulum of the court can never swing too far in one direction.

Option 2: The Fiji Model, or Elite Centripetalism

In Fiji, the voting system aims to build consensus by forcing parties to cater to multiple ethnic groups. But to fix the US Supreme Court, the challenge is to get presidents to pick wise jurists for their legal minds, not for their partisan ideology, and to get both divided politicians to vote to confirm them, without embarrassing dysfunction.

There are a few ways this could work, but in an ideal world, Supreme Court confirmations would require two-thirds, or even three-fourths, of votes in the US Senate. This would produce a moderating effect, because nobody would get confirmed without winning over at least some of “the other side.”

Obviously, this wouldn’t work in the current climate, because some extremist Republicans in the Senate would gladly leave a Supreme Court seat vacant rather than voting for a nominee from a Democratic president.

That’s why this reform would have to be combined with an institutional change that forces a sufficient number of incumbent justices from the majority side to recuse from cases, neutralizing their power, until a replacement had been confirmed.

So, if a justice retires from a 6-3 majority, leaving a 5-3 majority, the rule would stipulate that there would be a set period to confirm a replacement (let’s say 90 days from the nomination). Beyond that period, two justices from the majority side would be forced to recuse for all future cases, leaving an even 3-3 split, until a new justice was confirmed. That would create a strong incentive to process appointments swiftly and fairly. If this model also used a British-style independent commission to vet and propose potential appointments, even better.

Republicans will cry foul. Should they?

Republicans, of course, are likely to oppose any reforms. After all, they’ve got a solid majority on the court indefinitely. Why would they agree to any changes? Well, they won’t. But it’s hard for Republicans to claim they’re the victims in the American judiciary.

Stretching back to Nixon’s presidency beginning in 1969, Republican presidents have appointed 17 Supreme Court justices, compared to just six from Democratic presidents over that period, even though there have been eight presidential elections won by Republicans and six by Democrats over that stretch. (However, it’s noteworthy that two of those eight Republican victories came in elections where the Democratic presidential candidate received more votes—2000 and 2016).

Put bluntly, Democrats have won more votes than Republicans in 57 percent of the last 14 presidential elections, but Democratic presidents have only nominated 26 percent of the Supreme Court justices over that same period. Does that seem democratic?

So, my proposal is this: Democrats should twin any expansion of the court with serious reform of it. If they’re going to try to even the numbers a bit, which is a risky political strategy, they should do so only in accordance with broader reforms that permanently make the court fairer and more democratic. There are multiple good options, but we should go big. This is an unsustainable institution in its current form and it needs substnative reform.

But if reforms aren’t part of the Democratic proposals, and it’s just about expanding teh court, Republicans will simply plan retribution and their own expansion of the court at the soonest opportunity, and we’ll be back to an even worse version of square one. The cycle of toxic politics will worsen.

America is no longer like other functional democracies. It is a deeply divided place with broken institutions, creaking under the weight of crushing polarization and outdated models. But there are pathways to fixing it, if we only know where to look for inspiration. In this instance, we can learn from two forgotten islands nations: Comoros and Fiji.

Thank you for reading The Garden of Forking Paths. I love writing for you. If you’d like to give me more time to do so, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription, so you get access to more articles and I can devote more time to researching and writing for you. And please share this widely, on Twitter, Threads, Mastodon, Post, ye olde fashioned e-mail, or smoke signal, according to your preference.

Thank you for this article. We need to balance the court in order to reduce the polarization. We cannot function if the judiciary is seen as biased.

Some great solutions for sure, Brian. However, when our Justices themselves, break the rules …. And clearly face no consequences, there is a far larger problem.