Thank you for reading The Garden of Forking Paths. This edition is for everyone, but if you value my work, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription. It’s less than $1/week and it keeps this sustainable. Alternatively, consider supporting my work by buying my new book—FLUKE—recently named a Waterstones Best Book of 2024.

Many of us are experiencing acute symptoms of intense stress and anxiety. The underlying disease: world affairs, particularly the terrifying, looming election.

The medieval meme below artfully captures my internal feelings rather well, as I would like nothing more than to write about some intriguing esoteric intellectual fascination such as the virtues of service magicians or why humans don’t have tails, but I sometimes feel compelled, even obligated, to write about US politics because the stakes are so high and the dangers so great.

But here’s the thing: we all need a break, too.

I have therefore arrived in your inbox to give your brain something to think about that has the most wonderful virtue of being totally unrelated to a certain Donald J. Trump. Rest assured, dear reader, that when I offer you these intellectual curiosities—of octopuses and witches and murder mystery puzzles and telescopes on the moon—that zero of these ideas are closely related to impending dystopia.1 And on that happy note, here are my recommendations to satiate your mind:

Placebo Science Is Rooted in Witch Hunts

In 1599, a woman named Marthe Brossier was possessed by the devil in the Loire Valley. Or, so she claimed. The evidence appeared overwhelming to believers: she would gnash her teeth and writhe with the most grotesque expressions on her face. She could be pricked with pins without bleeding. And she had an uncanny ability to extend her tongue far beyond the length of a normal person. (Or, as a contemporary text put it more charmingly: “she had blared out her tongue very farre”).

As Kristen French explains in Nautilus, there may, however, have been an ulterior motive in these displays of demonic possession:

At the time, a violent conflict was afoot between Catholics and Protestants in France. Brossier came from a Catholic community and her demon claimed, among other things, that all Protestants belonged to Satan. Fearing political consequences, King Henry IV sent a medical commission to study the girl in private.

Unfortunately, without access to modern scientific instruments, there was no readily available Demon Possession Rapid Antigen test, or whatever its late 16th century equivalent would be. So, these boffins of the late Middle Ages had to devise a new strategy to accurately discern whether Brossier was really possessed, or if she was faking it.

With some clever scheming, they came up with an ingenious ruse. They gathered two types of objects. Half of them were fake relics, just random objects that unequivocally had no holy powers whatsoever. These objects, which included vessels of water, were unconsecrated and therefore free from any genuine connection with the divine.

Alongside these sham relics, they gathered another set of holy items—objects apparently imbued with godliness, which would presumably create quite an effect when placed in contact with a human body colonized by a demon.

For forty days, they tested Brossier. And, as French describes, she failed the test: “When a sham relic was held against her skin, she would scream as though it were made of fire.” She was faking it.

This, it turns out, was one of several medieval precursors to the rise of placebo trials in the later scientific method. And, according to recent research published in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, it was rooted in the remarkably sophisticated ideas about causal inference from the late 14th/early 15th century French theologian Jean Gerson.

Alas, every scientific insight can be both used and abused. Gerson’s insights helped pave the way for tragically vicious unscientific witch hunts that led to the torture and murder of innocent women, but they also provided the precursor for the logic used in placebo-based evaluations of modern medicine.

The Quest to Build a Telescope on the Moon

I recently attended a dinner in which I had the lucky privilege to find myself seated next to a top-notch science writer, Matthew Hutson. I was, I sheepishly admitted, not terribly familiar with his work, so I asked him:

“What’s the most recent topic you wrote about?”

“The quest to build a telescope on the moon,” he replied.

Well, that’s a good answer, I thought to myself. I vowed to read it. I have now happily fulfilled that vow and can therefore heartily recommend learning about why one might want to build a telescope on the moon and how it could be achieved.

As Hutson writes in The New Yorker:

Unlike telescopes such as the Hubble and the James Webb, which are made from mirrors and lenses, FarView would comprise a hundred thousand metal antennas made on-site by autonomous robots. It would cover a Baltimore-size swath of the moon. To show the FarView site up close, Carol drew a big square filled with dots. Each dot represented a cluster of four hundred antennas; all the clusters together would be sensitive enough to detect a cell phone on Pluto. They would perceive light that is nearly undetectable from Earth: radio waves from a mysterious period known as the Cosmic Dark Ages.

Autonomous robots building a city-sized telescope on the moon? You, sir, already had my curiosity, now you have my attention. Please proceed!

The moon has the advantage of being hundreds of thousands of miles away from earthly electronics; on the far side of the moon, in particular, there’s virtually no noise from human technology or the Earth’s magnetosphere…If FarView is built, it would be able to detect some of the oldest light in existence. The universe began 13.8 billion years ago as a dense, fast-expanding soup of matter and energy; around three hundred and eighty thousand years later, it had cooled enough for hydrogen atoms to hold together. After that came the Cosmic Dark Ages: millions of years without stars or galaxies, a period we know very little about.

I highly recommend the entire article. And if topics like telescopes on the moon intrigue you, you can check out some of Hutson’s other recent articles about going on an acid trip and beginning to detect intelligence everywhere or whether scientists can persuade the body to regrow its own limbs.

Ludwig (TV)

Every so often, you come across a TV show that seems tailor-made for you. For me, Ludwig is that show.

Its premise is beguiling: a police detective disappears, but leaves a note telling his wife not to contact the authorities. Following these instructions, his wife contacts the missing detective’s brother, a social misfit genius who makes his living creating puzzles under the pseudonym “Ludwig.”

But wait! It turns out the missing detective and the puzzle master are identical twins, which leads to a brainwave: what if the puzzle master poses as the missing detective and infiltrates the policing world so as to discover why he’s gone missing and what sinister machinations are afoot in the Cambridge police department? (That brainwave had the added benefit of making a good premise for a TV show).

This set-up ensures that every episode is a mystery within a mystery—as the puzzle master must try to figure out the larger mystery (why his brother disappeared) while being roped into solving mini-mysteries (which take the form of perplexing murders that have stumped the other less clever detectives in the Cambridge police). It’s smart, charming, lighthearted, funny, and flawlessly written. Plus, it stars David Mitchell, who is perhaps the greatest living British comedic actor (if you haven’t watched him in Peep Show, do sort that out sooner rather than later).

Freeloaders Will Be Punched by an Octopus

Okay, fine, that’s not the exact title of the article, but it might as well be. Longtime readers of The Garden of Forking Paths will recall that I am fascinated by octopuses, the smartest form of an alien-like intelligence on Earth, which I wrote about in this piece linked below—one of my favorite essays I’ve ever worked on:

Anyway, the reason I’m writing about these sublime creatures yet again is that new, recently published research has demonstrated:

Octopuses hunt with other species, acting as ringleaders in roving groups as they search for prey. Helpful fish act like scouts, notifying the group when they spot a tasty little treat lurking in the coral. But the octopuses are in charge. “These fish function as an extended sensory system for the octopus,” one researcher explained to Mirjam Guesgen of VICE. “The octopus can basically sample or explore the environment just by watching them.”

However, octopuses don’t like freeloaders, so if a fish is just loitering around and hoping to get a nice little meal without doing any actual work, the octopus will do what must be done: it will punch the fish. (No, I’m not kidding).

Here’s a video from New Scientist showcasing this extraordinary talent:

The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry (Film)

This film came out last year, based on the 2012 novel by Rachel Joyce, and I completely missed it. I watched it two weeks ago—and was utterly delighted and moved by it.

It’s a film about an elderly man with a relatively boring, commonplace life, long closed off to the world emotionally and physically after facing a personal tragedy.

And then, a blast from his past arrives in the post: news from a former friend that she’s dying. He writes her a condolences letter and goes to mail it. But as he walks to the postbox, he’s suddenly beset by an impulse to just keep walking. Eventually, he decides to walk across the length of England to hand deliver the letter to his former friend in her hospice, and thus unleashes the drama that presents such a moving insight into what makes us human—and how being open to the extraordinary, rather than the banal and routine, can act like a long overdue salve to a deeply wounded soul.

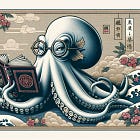

The Political Might of Early 20th Century Cat Ladies

Okay, I lied, there will be two teensy, tiny Official Brain Food™ recommendations that are marginally related to the 2024 election, but they’re too scintillating to pass up.

First: it turns out that cat ladies have been a potent political force since much earlier in American history. As this delightful article in JSTOR Daily showcases—based largely on archives at Johns Hopkins and the work of Southern Connecticut State University professor emeritus Kenneth Florey—the connection between cats and women voting goes back well beyond J.D. Vance’s now-infamous accusation about the dominance of “childless cat ladies” in the halls of power.

As Natalie Kinkade chronicles, this was a feature of early 20th century politics and the battle over suffrage:

Before internet memes, postcards offered a popular, accessible, shareable means to combine image and word…More than a thousand varieties of pro-and anti-suffrage-themed postcards were produced then, 200 of which are included in “Votes and Petticoats,” a Johns Hopkins University digital collection available on JSTOR. Of these, a significant number, curiously, depict cats—both as women’s pets and as women…

…Associations between ladies, cats, and cat ladies—childless and otherwise—are rooted in a long, complicated cultural history. In Edwardian times, cats were linked to women as creatures of the domestic domain: woman was Angel of the House, the cat her companion, both of them sweet, warm, helpful, and cute. At the same time, animal lovers, “spinsters,” and suffragists represented overlapping, suspect categories of womanhood. It’s the perennial paradox in which women find themselves: somehow looked down upon while also placed on a pedestal.

Do read the whole article, but in the meantime, I’ll provide you these glimpses of its fascinating delights with these wonderful images from the collection:

Then, there’s this poignant one, depicting a suffragette who had been beaten down by impossible odds and relentless abuse, but would remain in the fight. As the postcard insists, I’m a Suffer Yet, continuing her battle, despite the wounds.

The Real Thirteen Keys for Winning the White House

If you read my latest deep dive on polling, you’ll know that I do not think highly of Allan Lichtman’s “Thirteen Keys” approach to presidential forecasting. (Put bluntly, it’s pseudoscientific mumbo-jumbo). But we’re in luck, for the writers at McSweeney’s have discovered the real keys—and they’re somewhat unexpected.

For example, there’s Key 6:

The Sentience Key. This key is awarded if the candidate can persuade the public that they are conscious. Not environmentally conscious or socially conscious; that has never mattered. Rather, voters love knowing that the person they elect is able to perceive the external world. For this reason, unicellular organisms rarely secure the presidency.

Or, my favorite, Key 10:

The Being Rude to a Dog Key. Since the founding of this nation, no candidate has ever won the presidency after being caught publicly being rude to a dog. Our extensive study of the American people has determined that they like dogs and don’t want a leader who refuses to engage in cuddles when all indicators would imply that it is cuddle time.

Thanks for reading. If you enjoy my work, you might also enjoy upgrading to a paid subscription! I don’t want to alarm you, but science has shown that freeloaders will be punched by an octopus, so consider yourself warned. And do try to enjoy spending at least a bit of time jesting rather than jousting in these stressful times. Enjoy your weekend!

When I say “zero,” I mean “two,” but in my defense they are only *marginally* related.

🤣 “For this reason, unicellular organisms rarely secure the presidency.”

I watched the Detectorists based on your recommendation and was not disappointed, so I'm adding Ludwig to the lineup now! Thanks for the much needed break from all the horrors of living these days.