Blood Diamonds and the Lottery of Earth

How geography and geology shapes our destinies.

Thank you for reading The Garden of Forking Paths. This article is a free edition from the archive, but if you’d like to support my work so I can devote more time to writing for you (and to unlock full access to 210+ articles!), please upgrade to a paid subscription. Your support makes this possible.

Are our lives—and our histories—just the accidental playthings of geography and geology?

Look to any event in history and you’ll discover a tangled tapestry, thousands upon thousands of distinct threads—some long, some short—that were woven together by often accidental forces to create that exact event with those exact people in that exact time.

History books and human narratives emphasize our roles, bipedal masters of our own destinies. But too often, far deeper forces are ignored: we are creatures of a specific tectonic snapshot on a contingent planet. And our actions as a species often interact with those invisible, longstanding tectonic forces to create absurdly peculiar outcomes—some triumphs, others tragedies.

In one astonishing example—an example I cut from the final draft of Fluke for space reasons—I’m going to show you how an ancient inland sea, an 18th century English inventor, the shape of coastlines carved out over millions of years, a Philadelphia-based marketing guru, long-term erosion, and West African rebels descended from those freed from American slavery…combined to produce a violent, bloody conflict. And it was all fueled by cut, shimmering little minerals that suddenly and arbitrarily became valuable.

It’s a true story that will make you question how history works—and how much our lives are affected by unseen forces beyond our control.

Is “environmental determinism” an intellectual sin?

History isn’t written exclusively by human authors. Instead, we interact with our environment. Our decisions, our cultures, and our lives are shaped by the natural world and everything in it. This idea—that Saudi Arabia would be radically different today if it didn’t have oil, or that American history would have unfolded differently if it wasn’t separated from Europe by the Atlantic Ocean—is so obvious that it seems commonplace.

Geography isn’t destiny, but it matters. And yet, explanations that prioritize geography or geology are too often dismissed.

To some, trying to suggest that human history is driven by geography or geology is one of the gravest sins of scholarly arguments. There are good reasons to be skeptical about placing too much emphasis on historic explanations that relegate human choices to the periphery. Writers throughout the ages have used geographic arguments to advance the most ridiculous, often racist claims.

One philosopher in ancient China, Guan Zhong, argued that people who lived near fast-flowing water were destined to be “greedy, uncouth, and warlike.” Hippocrates claimed that any people, such as the Scythians, who lived on a barren wasteland, were doomed to be infertile and impotent. More recently, European bigots used similar ideas to justify colonialism and enslavement.

In the 20th century, then, there was a long overdue academic reckoning, a well-deserved backlash against what was disparagingly deemed “environmental determinism” or “geographical determinism.” As critics pointed out, placing too much blame on geography could be used to absolve, even justify, atrocities inflicted by human action.

The scholarly debate got ugly after Jared Diamond’s surprising international bestseller, Guns, Germs, and Steel was published in 1997. Many anthropologists hated it, including one who later penned an article—in a scholarly journal no less—titled “F**k Jared Diamond.”

Some claimed Diamond was a racist apologist for colonialism. (As with any sweeping theory of human history, there were some errors and issues that were worthy of scrutiny and debate, but Diamond explicitly disavowed racism and condemned using geography as a stalking horse to whitewash atrocities).

But many of these scholarly critiques were ridiculous, and Diamond’s broad thrust about the role of earthly forces was clearly at least partially right: human history has been significantly shaped by arbitrary geographic and geological facts of our world. (If you’re interested in a long, but well-written defense of Guns, Germs, and Steel from a scholar who knows what he’s talking about, here’s a great Substack post on the subject by Davis Kedrosky).

This is admittedly all a bit abstract, the kind of discussion that agitates those of us with well-worn elbow patches. So, to see how these debates play out in the real world, let’s trace how and why many of you have ended up with a small little jewel-encrusted ring on your finger, or perhaps a glittering gemstone poking out of your earlobes—and later, how blood diamonds came to emerge as a funding source for deadly warfare.

This unknown story—or my stitching together of several lesser known stories—begins in 18th century England, in a charming, quaint little village, called Cromford.

The forgotten birthplace of the industrial revolution

In the mid-18th century, an Englishman named Richard Arkwright was busy working on a new invention to spin cotton. At first, he tried powering it with literal horsepower, but it was cumbersome, the horses eventually tired, and he sought a better solution. In 1769, he took out a patent for a “waterframe,” which could spin cotton using the power of flowing water.

He searched for a suitable location to deploy his invention and found it in Cromford, a tiny village nestled in the picturesque, rolling hills of Derbyshire. The nearby Bonsall Brook could power the mill, and there was also a constant supply of warm water, the runoff from industrial activity at a nearby lead mine. The Earth’s minerals and its waterways gave Arkwright the perfect spot to build Cromford mill.

It worked. So much so, in fact, that it sparked what we now know as the Industrial Revolution. Between 1770 and 1790, Arkwright’s invention spread across England, as hundreds of copycat mills opened shop, creating a booming industry of textile manufacturing, and an accompanying thirst for unlimited quantities of cotton.

Now, all they needed was a plentiful supply.

Enslavement and King Cotton

Around the same time that Arkwright was revolutionizing production in Cromford, European ships were sailing down the coast of West Africa, picking up Africans, enslaving them, and forcibly moving millions across the Atlantic. These horrifying atrocities mostly took place in the coastal areas of West Africa that were sometimes known as the Slave Coast.

Why didn’t the Europeans go inland? The answer likely lies with another geographic factor: the prevalence of tropical disease. When Europeans arrived in the Americas, they brought the diseases, and those diseases were deadly for the native population. But when Europeans arrived in West Africa, it was the explorers who began dying from diseases. Yellow fever, malaria, and heat exhaustion led to European sailors referring to the area as the “White Man’s Grave.”

Some historians suggest these divergent experiences with disease on either side of the Atlantic prompted Europeans to establish colonies in the Americas, but to only land ships in West Africa long enough to trade goods for people. Slave traders stuck to the coastlines—not providing development, but simply pumping people and resources outward, a strategy of exploitation and extraction.

Traces of these abhorrent policies are easily visible if you look at a map of modern West Africa. Before the Atlantic slave trade, many population centers were inland. Today, you can see where the boats stopped mostly by looking at the capital cities. Each one, from Dakar, Senegal to Porto-Novo, Benin, is on the coast, locations that were either settled by, or that grew exponentially due to their convenience to, slave traders and colonizers. (At first glance, Côte d’Ivoire appears to be an exception, but Abidjan—a coastal city that I lived in previously for my research—is by far the biggest city in the country).1

The ships that departed from West Africa took their enslaved human cargo to the Americas. That slave trade peaked in the 1780s, a decade after Arkwright’s mills created a surge in demand for cotton. Where did many of the enslaved people end up?

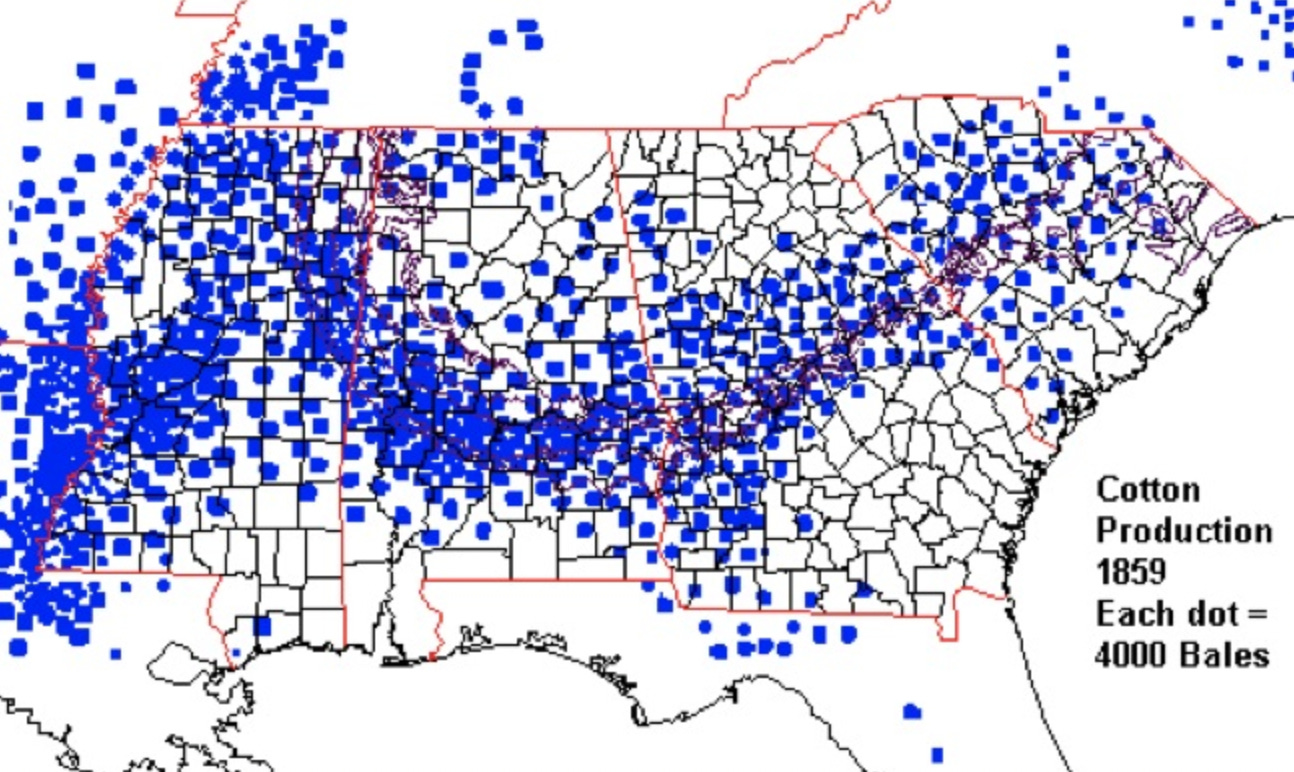

Again, the explanation lies partly with the “lottery of Earth.” Many enslaved people were eventually sold to plantations in the American deep south, in an area known as the Black Belt, named not for forced African transplants but for its rich, dark soils—soils forged by the remnants of millions of years of plankton that died along the coastline of an inland sea during the time of the dinosaurs. The swoop of that coastline and its eventual fertile soil is the same swoop of where plantations were mostly set-up before the American civil war.

Compare the shape of the coastline in the lower right section of land (passing through modern day Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina in particular) to the concentration of plantations in those states during the 1800s.

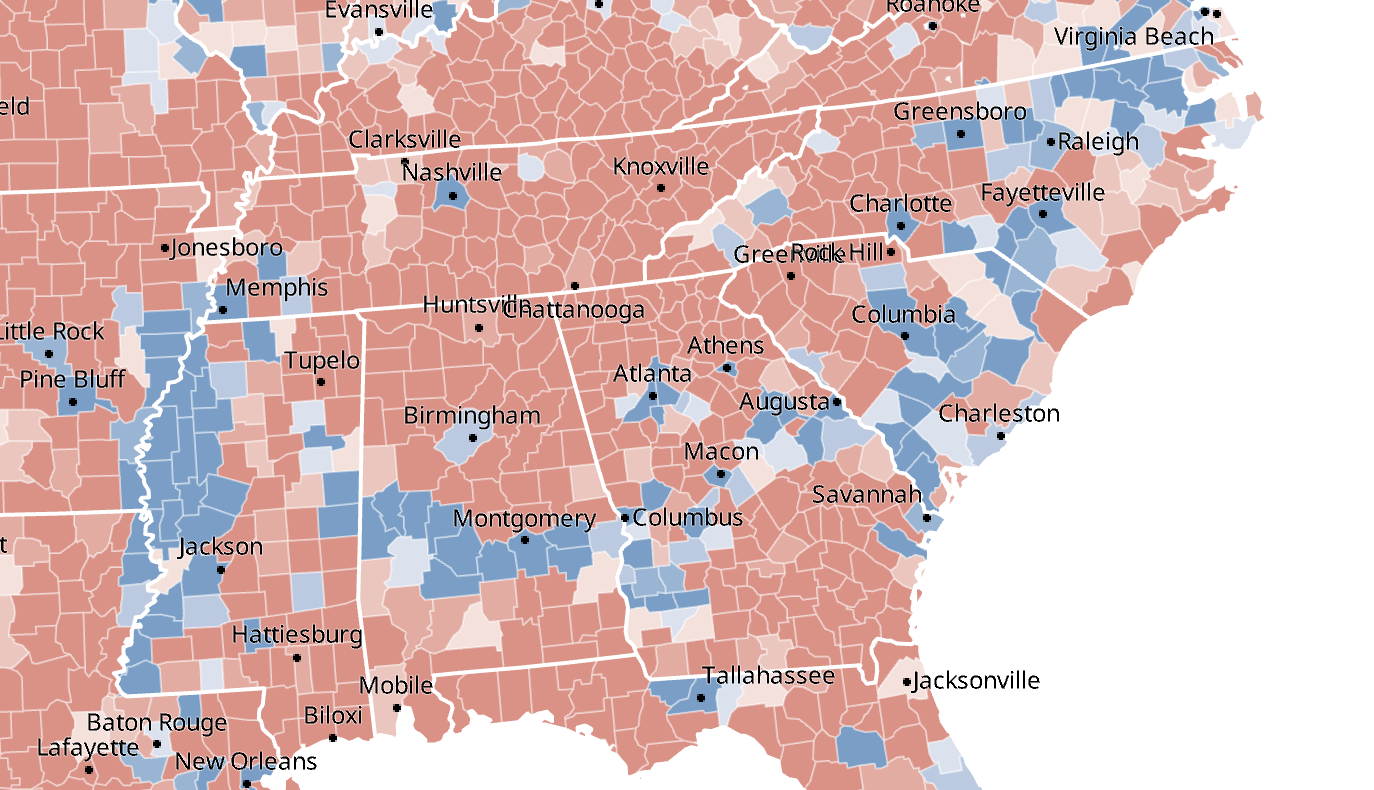

After the US civil war, many African-Americans had little choice but to stay near the land where they had previously been enslaved. (As an aside, the shape of the inland sea—and the demographic remnants of it through plantation locations—is still visible in US election results, since African-Americans tend to vote for Democrats. Below, you can see the swoop shape of the ancient inland sea in county-level election results from 2008, when it was most pronounced.)

Thousands of formerly enslaved people who were freed after the US Civil War moved back to West Africa, settling in the renamed cities of Freetown, Sierra Leone and, especially, Monrovia, Liberia. (Monrovia was named after former U.S. president James Monroe, making it, after Washington, D.C., the second national capital named after an American leader).

The Americo-Liberians, as they became known, kept Americanized names, practiced Christianity, and quickly dominated the political class in their new nation. But what they didn’t know—and wouldn’t become clear for generations—is that their descendants were also about to become victims of accidental geography and geology.

That’s because the rivers coursing through their land were full of a mineral that would later tear their country apart—and lead to the deaths of countless innocent people.

Diamonds weren’t always a girl’s best friend

Five years after the American civil war ended, at the other end of Africa from Liberia, prospectors found diamonds embedded deep in the earth near South Africa’s Orange River. This triggered a diamond rush around the town of Kimberley, which was home to a series of vertical shafts now known as “kimberlite pipes,” named after the town.

These kimberlites are formed deep in the mantle of the Earth, roughly ninety-five to 200 miles below the surface. Because the gems at Kimberley remained buried deep, a substantial investment was needed to prize them out of the earth. That created serious financial risk. If other diamond discoveries were made, it could flood the market, causing the price to plummet.

Plus, in those days, there wasn’t much of a global market for diamonds. They were rarely used as gemstones. Few got engaged with diamond rings. People just weren’t that interested in diamonds.

Then, in 1888, investors founded De Beers Consolidated Mines, Ltd. Over the next several decades, they cornered the diamond market, buying up land and diamonds to ensure that prices would stay high by keeping public supply low.

But to really get a return on their investment, they would have to change humanity’s relationship to diamonds. Back then, most saw diamonds as a luxury reserved for the aristocracy. To change that perception, De Beers hired a Philadelphia ad agency, N.W. Ayer & Son (the same ad agency that would later, in 1981, come up with the US Army slogan: “Be all that you can be.”) The ad agency was hired to convince young men and women that “the larger and finer the diamond, the greater the expression of love.”

The marketing firm gave diamonds to Hollywood stars to wear on the silver screen. N.W. Ayers even organized thousands of lectures in schools across the United States, boasting that “all of these lectures revolve around the diamond engagement ring, and are reaching thousands of girls in their assemblies, classes and informal meetings in our leading educational institutions.”

In a strategy memo, the agency explained that “We spread the word of diamonds worn by stars of screen and stage, by wives and daughters of political leaders, by any woman who can make the grocer's wife and the mechanic's sweetheart say ‘I wish I had what she has.’”

Crucially, they also wanted to be sure that used diamonds wouldn’t undercut their market for new ones. They wanted to make it socially unacceptable to buy somebody’s else’s symbol of love.

In 1947, N.W. Ayers proposed a new slogan for De Beers: “A diamond is forever.”

It worked. In 1939, De Beers sold $23 million worth of diamonds in America. Four decades later, that figure was $2.1 billion. Today, the total value of the global diamond market is roughly $97 billion.

The success of that Philadelphia ad agency—and the vagaries of tectonic plates and geological erosion—forever changed the trajectory of the West African territories home to thousands of formerly enslaved people, particularly in Liberia and Sierra Leone.

But there was a crucial, consequential difference. Unlike the diamonds buried deep beneath South Africa, the deposits in West Africa were mostly alluvial diamonds, meaning that they lay not in deep shafts hidden below the Earth’s crust, but at the bottom of riverbeds.

Over millions of years, kimberlite pipes can erode, leaving the diamonds closer to the surface. Eventually, through rain and erosion, many of those diamonds end up being washed away, settling in riverbeds, out of sight, waiting to be plucked from the water.

Fittingly, on Valentine’s Day in 1972, the world’s largest ever alluvial diamond was discovered on one of those riverbeds: the Star of Sierra Leone. It was worth millions, and it sparked a diamond rush. West Africa’s rivers suddenly filled with people desperately searching for the next big gemstone.

Those same rivers would soon run red with blood.

The type of diamond determines the type of war

You may have heard of “conflict diamonds” or “blood diamonds,” but what’s less understood is that different kinds of diamonds create different kinds of wars.

Kimberlite (buried deep) diamonds require expensive mining equipment, major capital investment, and physical control of the territory being mined. Territories that rely on mining diamonds from deep within the earth, such as South Africa and Botswana, can maintain control of a fixed location, issue mining permits, and capture tax revenues that can produce more widespread development. Those countries usually get richer as a result.

In those geological conditions, rebels can only use kimberlite diamonds to fund wars if they’ve already captured significant chunks of territory. The barrier to entry for a civil war is much higher. You need to first control the land, then you can use the gems to buy guns and pay soldiers.

Alluvial (river) diamonds are different. Anyone with a shovel and a sieve can become a diamond miner, including children. Prospectors don’t need to own the land, because it’s impossible to defend and patrol entire riverbanks. Anyone can just wade into the water and hope to strike it rich. This tends to reduce national investment in diamond mining, because governments are unable to properly control and tax the revenues from such an easily captured resource. That tends to keep the country poorer.

But it also means that rebels can easily wade into rivers, collect diamonds, and rapidly trade them for AK-47s. No land needed.

Such are the wrinkles of geography. It’s not just that diamonds matter, but that the geological origin of the diamonds can determine the trajectory of history.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, diamond-driven civil wars broke out, first in Liberia, then in Sierra Leone. The gems both motivated and fueled the conflicts. The two wars were also linked, as the warlord Charles Taylor (note the Americanized name) led the rebel movement in Liberia, then sponsored rebels in Sierra Leone.

Taylor, who became the president of Liberia in 1997, was eventually toppled from power, arrested, and put on trial for war crimes at The Hague. When he was convicted and sentenced in 2012, he was sent to prison in Durham, England, just a few hours drive from Cromford Mill, where intense industrial demand for cotton had originated.

History is never simple

Another writer would tell this story by stitching together different angles, emphasizing some aspects more, others less.

History is therefore not just what happened, but is rather a written narrative, often filtered through a single mind, built upon an arbitrarily selected pile of surviving evidence, and subjectively stitched together.

Here, the exact contours of this story are less important than the idea: that our lives are swayed by natural forces, even as we obsess about our histories as though they are solely authored by us. They’re not, and the more that we understand ourselves as an interacting component in a much larger, maddeningly complex system that we call the Earth, the fewer mistakes we’ll make when we try to learn from our own histories, tragic or triumphant.

And now, you’ll also know that any of those shimmering jewels you may have—or perhaps that you’ve given to someone else—are largely valuable due to one of the most effective marketing campaigns of all-time, capitalizing on a mineral that has been spit out of the Earth in strange ways, its hidden value dreamed up and unlocked by a random guy in Philadelphia. And a few decades later, his advertising genius would inadvertently spark the deaths of countless people, scrounging for the arbitrarily luxury gems in riverbeds.

Thank you for reading The Garden of Forking Paths. If you enjoyed this edition, or learned something new, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to support my work. And if you enjoyed this piece, it is probable that you’d also enjoy my book about contingency and chaos theory: FLUKE.

The official capital, Yamoussoukro, was selected because it was the birthplace of the country’s former dictator, Félix Houphouët-Boigny. It’s home, bizarrely, to the largest church in the world (by some measures).