Why We Need Fools: Jesters, Power, and Cults of Personality

The history of court jesters and fools reveals lessons about the nature of modern power, from narcissistic hubris to cults of personality—and the necessity of being told when you're wrong.

Thank you for reading The Garden of Forking Paths. If you’d like to support my research and writing, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription (it’s only $4/month). Alternatively, you can support me by ordering my new book, FLUKE: Chance, Chaos, and Why Everything We Do Matters.

“And, let me tell you, fools have another gift which is not to be despised. They’re the only ones who speak frankly and tell the truth, and what is more praiseworthy than truth?”

—Desiderius Erasmus, Praise of Folly (1509)

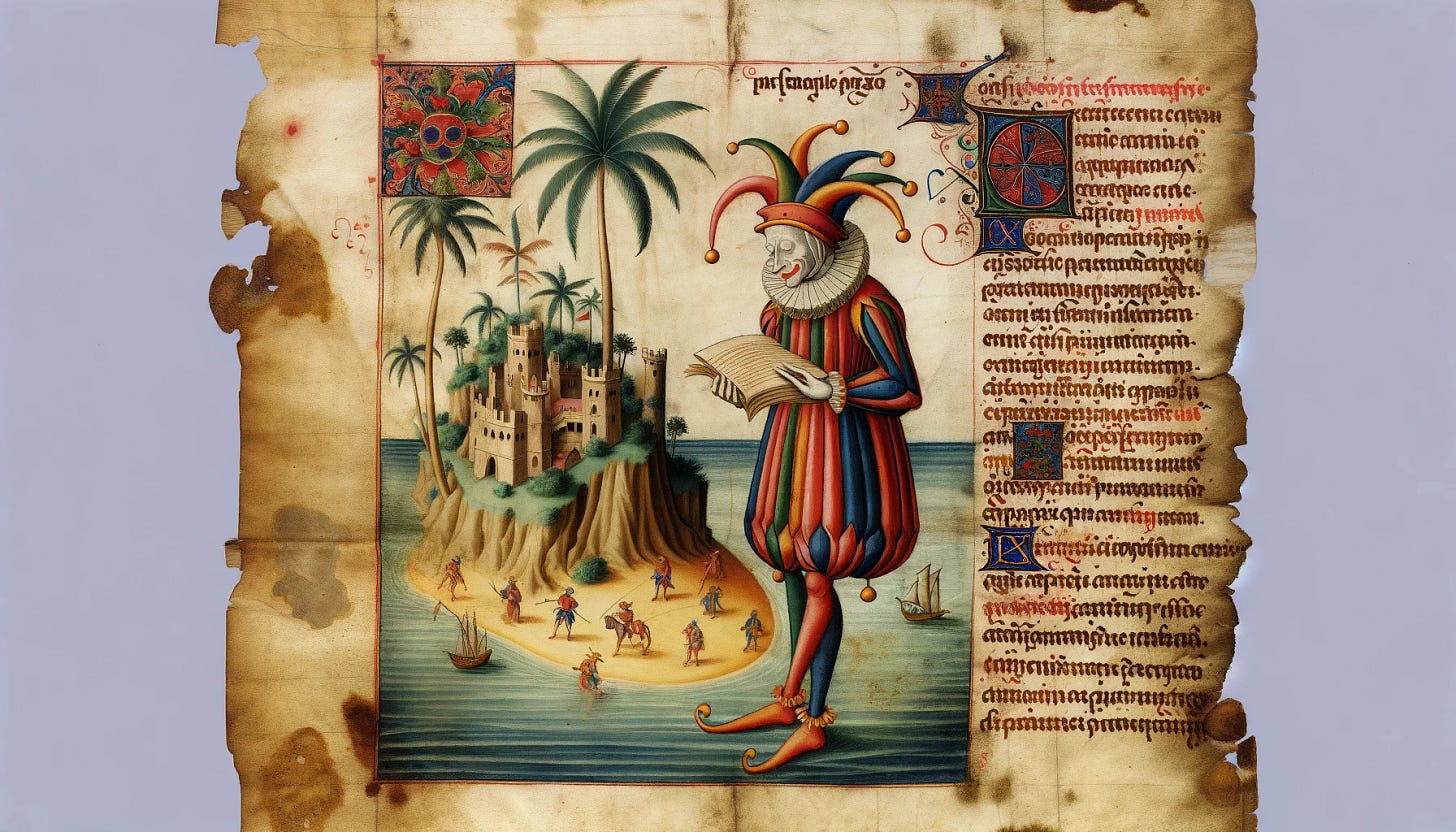

Court jesters, known to modern times through the fools of Shakespearean drama, are a nearly universal human impulse. The first known records of jesters stretch back more than 4,000 years, to ancient Egypt, though they crop up globally, from China and France to Italy and England, spanning thousands of years. Fools are a feature of complex civilizations.

But, perhaps a bit unexpectedly, the history of jesters teaches lessons about the nature of power—providing unique wisdom about leadership, truth-telling, narcissism, ego, hubris, and humor, from the ancient pharaohs to Donald Trump.

I: The Court Jester of Tonga

Jesse Bogdonoff was born on April Fools’ Day. Little did he know that later in life, he would play one of the greatest roles in history: the king’s fool.

Bogdonoff—saxophonist, financial planner, and proponent of the healing power of magnets—added an unexpected line to his CV just over two decades ago: Court Jester to the kingdom of Tonga.

But our story begins earlier, in the 1980s, when a Hong Kong-based businessman conjured up a get-rich-quick scheme, convincing the Tongan king to sell passports, primarily marketed at those hoping to escape Hong Kong before its handover to the Chinese government in the late 1990s.

Some of the first Tongan passports were sold to exiled Filipino dictator and kleptocrat Ferdinand Marcos, his two daughters, and his wife Imelda. Over the first eight years of the scheme, five thousand passports were sold—netting the kingdom of Tonga the staggering sum of $30 million (roughly equivalent to the entire annual budget for the Tongan government).

To safeguard this infusion of cash, the Tongan king invested $20 million of the funds with the Bank of America’s San Francisco branch, where it sat, mostly untouched. Until Jesse Bogdonoff spotted an opportunity.

Bodgonoff tried calling the Tongan government, but had no luck getting through to anyone. So, in 1994, he hopped on a plane, and ended up in an undeveloped paradise, a land of free-roaming pigs and few streetlights. On the third day, he met the king, Taufa’ahau Tupou IV, who greeted him in his office, clad in a muumuu, in a royal office decked out with a treadmill.

Bogdonoff convinced the Tongan king to invest the passport millions that were sitting untouched, guaranteeing him a quick, easy return. The king agreed. And in the bull market of the 1990s, it paid off: the fund earned $11.8 million over the next five years.

In 1999, Bogdonoff, now ensconced as the king’s money man, decided to leave Bank of America. And once outside the bank, strict regulations prevented him from maintaining the account independently. But there was a loophole: if Bogdonoff became directly employed by the kingdom, he could keep managing the money. And that’s when a brainwave struck the man born on April Fools’ Day.

“I’m a natural-born fool, and you’re a king, and I’d like to become your jester,” Bodgonoff proposed. The king, unsure at first, eventually accepted. Bogdonoff was proclaimed “King of Jesters and Jester to the King to fulfill his royal duty sharing mirthful wisdom and joy as a special goodwill ambassador to the world.”

Unfortunately for Tonga, the next trick Bogdonoff performed was to make all the money disappear. He invested it foolishly, in risky strategies that imploded. The money—the rainy day fund for Tonga’s impoverished population—was gone.

Today, Bogdonoff, who has not set foot back in Tonga since the fiasco, runs the “Open Window Institute for Emotional Freedom” in Orange County, California, offering clients hypnosis therapy. You, too, can schedule a free 45 minute “break-through call (spaces are limited)” with the one-time court jester of Tonga, who promises, as all good jesters must, to help you “with a smile.”

In the annals of jesters, Bogdonoff’s catastrophic folly in Tonga was an outlier. Most fools, as we shall now see, were an integral component of power wisely wielded, from ancient China to medieval Europe.

II: A Jester’s History of the World

According to Beatrice Otto, author of Fools are Everywhere: The Court Jester Around the World, the earliest known jesters date to ancient Egypt, during the Sixth Dynasty (around 2,323 to 2,150 BC; the jester was a dancing dwarf).

“The precondition for the emergence of jesters are minimal—some courtlike institution in the form of a head honcho with a partly dependent entourage,” Otto explains. “The evidence points to this having existed across the globe and across history, in most of the major civilizations of the world and many of the minor ones.” As Otto points out, even Montezuma II, the greatest Aztec king was known to be “an avid jester keeper.”

While we tend to think of jesters in English courts, or the fools of Shakespeare and their Italian and French counterparts, the longest-running line of court jesters existed not in Europe, but in China. There, jesters had wonderful names, often involving modified nouns: “Tall Towering Mountain,” “Wild Pig,” “Going Round in Circles,” “Openly Flawless Jade,” or “Subtle Reformer King.”

While the European period of court jesters lasted around four centuries, there were Chinese jesters for around two thousand years.

In one instance, a Chinese jester in the sixth century AD named “Moving Bucket” angered the emperor and was sentenced to death. As he was about to be executed, he asked to speak his mind one last time. The king obliged—and the jester spoke, arguing that it would, in fact, be better if he were not beheaded: “If your majesty takes my head, it will be absolutely useless to you. If I lose my head, it’ll be extremely painful to me.” The king laughed, accepted this logic, and released Moving Bucket.

One Chinese jester was named “Newly Polished Mirror,” an allusion to the fact that these characters in royal courts could provide an honest accounting of the monarch’s strengths and weaknesses, a rare, straightforward reflection in a world where the walls seemed to be made out of the funhouse mirrors of obsequious flattery and fawning, uncritical praise.

Some of the jesters were known as “natural fools,” people born with some visible defect or mental condition, inadvertently comical to a crueler world that found such abnormalities laughable. These included dwarfs and hunchbacks, who could deliver nonthreatening criticism to a ruler, for, as Otto highlights, “a dwarf or hunchback could not physically look down on a king.” In that way, their own imperfection offered an opening for royal introspection, as a visibly flawed servant suggested that it might be time to examine one’s own internal flaws.

Other times, kings were said to swap places with fools, a reminder of humility, a more comical reincarnation of the “remember thou art mortal” mantra that was said to be given to Roman emperors.

These fools became close confidantes of kings and queens, developing a familiarity with royalty that went beyond even their most senior advisers. Will Sommers, the favored jester of Henry VIII, was able to call the king “Harry” or “Uncle,” the latter a term of endearment co-opted for use by the Fool in King Lear.

But fools weren’t just royal ornaments or companions. They served a crucial purpose—a purpose that too many of our leaders today have ignored due to their narcissistic hubris.

III: On Wise Fools & “Happy Unhappy” Answers

One of Elizabeth I’s top fools, Tarlton, was recruited haphazardly, from a passing conversation. As one account from 1662 recalled: “Here he was in the field, keeping his Father’s Swine, when a Servant of Robert Earl of Leicester…was so highly pleased with his happy unhappy answers, that he brought him to Court, where he became the most famous Jester to Queen Elizabeth.” (The choice was a wise one, as Tarlton “told the Queen more of her faults, than most of her Chaplains, and cured her Melancholy better than all of her Physicians.”

The crucial phrase in that account—happy unhappy answers—captures the momentous power and influence of jesters throughout history, while also explaining how they could perform their duties. As Otto notes: “The common ground of the jester everywhere lies in his duty to entertain and his license to speak freely, even if this earns the ire of his master.” The Chinese nickname for court jesters—wu guo chi—means “fools of no offense.”

Jesters were therefore unique in court: they could speak truth to power. Courtiers who lived in fear produced comforting lies. Fools provided much-needed honesty.

The ability to speak freely, reserved only for fools, earned them respect. Medieval courts noted the wisdom of the “foolosopher” or the “sage fool.” In modern parlance, we still have one linguistic holdover from the paradox of fools as keepers of sagacity; as Otto points out, the word “oxymoron” is derived from oxus, meaning “sharp” and moros, meaning “fool.” (One 8th/9th century fool with the magnificent name “Buhlul the Madman,” also known as the “Lunatic of Kufa,” was widely regarded as one of the great sages of his era).

In one instance, George Buchanan, the jester to the 16th century King James VI of Scotland, used his unique privileges to teach the king a valuable lesson.

The jester noticed that the king was prone to signing documents without even a cursory glance, which left him vulnerable to manipulation. So, the jester penned a document that would transfer royal authority from King James to his humble jester for a period of fifteen days. As Otto explains, when the jester then went to sit on the throne, “The king at this was greatly offended, until George shewed him his seal and signature. From that day the king always knew what he signed.”

Humiliating a king would have gotten anyone else killed, but jesters survived precisely because their role was to say and do what nobody else dared. However, even the loyal fool could sometimes go too far.

In a story that’s likely apocryphal, the famous French jester Triboulet was said to have slapped the king on his butt, an extraordinary indiscretion. Outraged, the king threatened to execute Triboulet. However, he gave Triboulet one last ditch shot at survival: if the jester could come up with an apology that was even more offensive and insulting than the butt smack, his life would be spared.

Triboulet, always quick on his feet, retorted: “I’m so sorry, Your Majesty, I didn’t recognize you. I mistook you for the Queen.”

In another instance, it is said that Triboulet again found himself facing execution, but the merciful king decided to reward the jester for his loyal years of service. Triboulet was told that he would have to die, but that he could choose how he would die. “Good sire, by Saint Nitouche and Saint Pansard, patrons of madness,” Triboulet replied, “I ask to die of old age.” He did, in 1536.

Jesters, with their happy unhappy way of communicating, could also be used to break bad news to volatile kings. In 1340, England defeated France at the Battle of Sluys. It was a lopsided catastrophe; the French lost between 16,000 and 20,000 men, compared to just 400 English soldiers. And the French fleet lost 190 ships, compared to just two from England. Thousands of French troops drowned in the sea. Relaying this disastrous news was a perilous task, but the French fool was up to the challenge. Approaching the king, he said: “The English cowards! They don’t even have the guts to jump into the water like our brave French!”

Jesters became regarded as the most trustworthy people around court. They would say what others wouldn’t, advise a different course of action when they thought the king or queen was making a mistake, and could be relied upon to not sugar-coat disastrous events.

Through this trust, ambitious jesters had unique opportunities to sway royals to do their bidding. (As Otto explains, even Shakespeare highlighted that ambition, noting that Touchstone, the jester from As You Like It, was prone to using “his folly like a stalking-horse”).

Paradoxically, then, being a fool was a plum job that conferred immense power. This meant that jesterhood could be a magnet to short-term opportunists, who would temporarily try to don the cloak that demarcated true fools, attempting to pose as one to influence royal decisions. This problem of imposter fools grew so great that Scotland eventually passed perhaps the best-named law of all-time on January 19th, 1449: “The Act for the Away-Putting of Feynet [Feigned] Fools.”

But the punishments were no joke: anyone deemed to be a jester pretender would be liable to have their ears nailed (exactly what it sounds like) or have bits of their body amputated. For much of medieval history, fools were a serious business.

And their serious function—of being unafraid to speak truth to power—made their patrons better decision-makers.

Alas, such sage fools, from Triboulet to the Lunatic of Kufa, have few modern counterparts. Jesters, or something like them, have largely disappeared from modern halls of power, as thin-skinned narcissists construct auras of cult-like devotion around them, insisting that the Dear Leader can never make mistakes.

In the process, our leaders have engineered dysfunctional systems of power—many of which run our world—that routinely court avoidable catastrophe, all because of misplaced hubris and an inability to occasionally laugh at the honest truth of one’s own human failings.

IV: No Jesters in the Courts of Trump or Putin: Cults of Personality and the “Dictator Trap”

The wisdom of jesters lies with rulers who recognize that truth is more valuable than fawning admiration. And yet, we are often ruled by people who can’t take a joke—thin-skinned authoritarians who demand fealty. When they make a catastrophic mistake, it’s reality that’s wrong, never themselves. So, they make up lies— and then demand that their disciples parrot their lies as a loyalty test.1

To Trump, there is no worse fate than being laughed at. On social media, Trump routinely suggested that our enemies were “laughing up their sleeves” at America. And when NBC’s Saturday Night Live ridiculed him, he called for “retribution” against the network. For Trump, being reduced to a punchline is the pinnacle of humiliation. (There is some speculation that Trump decided to run for president in 2016 after Obama mocked him at the 2011 White House Correspondent’s Dinner).2

In an even more colorful example from Turkey, President Erdogan pressured the German government to prosecute a comedian who implied that Erdogan has sex with goats. In another case, as I previously highlighted:

A civil servant was arrested and tried for sharing a meme that compared Erdogan to Gollum, the miserable creature from The Lord of the Rings film trilogy. (The defense argued that the memes actually depicted Smeagol, Gollum’s alter-ego and his goodness within, forcing the judge to call for a recess to better understand the character, since he had not read the books or seen the films). Such absurdity is inevitable when rulers try to police comedy.

Thin-skinned egotism from narcissistic autocrats is exactly the opposite of the ethos of the jester, an inversion of a tried-and-tested system that, for thousands of years, allowed leaders to get honest feedback without losing face.

Today, for many (bad) leaders, truth spoken to power is viewed as an unforgivable affront, not an indispensable necessity. After all, anyone who has ever challenged Trump has been purged from his entourage, denounced as a RINO (Republican-in-Name-Only) even for the most minor transgressions. Regrettably, while there are plenty of unserious clowns surrounding them, there are no truth-telling jesters in the courts of Trump or Putin.

Instead, modern autocrats thirst only for unwavering fealty, eliminating those who question the myths that surround the leader. Through endless loyalty tests and public displays of unquestioning devotion, a cult of personality emerges.

No need to speak truth to power, because the powerful determine the truth.

While jesters puncture the myths and combat the lies that surround powerful figures, cults of personality do the opposite: they perpetuate falsehoods so effectively that the dictator begins to believe their own lies. The fake world constructed through displays of slavish devotion becomes the dictator’s reality.

When this happens, you end up with a phenomenon that I call “The Dictator Trap”:

They hear only from sycophants, and get bad advice. They misunderstand their population. They don’t see threats coming until it’s too late…despots rarely get told that their stupid ideas are stupid, or that their ill-conceived wars are likely to be catastrophic. Offering honest criticism is a deadly game and most advisers avoid doing so. Those who dare to gamble eventually lose and are purged. So over time, the advisers who remain are usually yes-men who act like bobbleheads, nodding along when the despot outlines some crackpot scheme.

For vast stretches of history, kings, queens, and other autocrats have understood this informational dilemma between loyalty and truth. For thousands of years, erudite rulers engineered an ingenious solution to become wiser—the jester. And yet, our modern despots, aspiring despots, and boardroom tyrants have forgotten that lesson, which, through their unchecked hubris, has meant the joke is on us, suffering from needless stupidity emanating from overly fragile egos.

V: Long Live the Jester

We need jesters.

Humor, the great disarmer, is the surest way to give “happy unhappy” answers, to ignore the decorum of deferential niceties—to keep the focus on what’s true, rather than what’s comforting. Though we need not dress modern jesters up in harlequin hats with baubles and force them to don special cloaks, good leaders understand the most potent lesson of the fool: that eliciting honest criticism—delivered good-naturedly—is the secret weapon of wisdom.

Thank you for reading The Garden of Forking Paths. This article was for everyone, but if you learned something, or found this interesting, or are just a lovely person and want to support me so I can keep writing for you, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription for just $4/month. Or, consider buying my new book: FLUKE: Chance, Chaos, and Why Everything We Do Matters. (I had the recent pleasure of discussing Fluke on MSNBC with fellow Carleton College alum Jonathan Capehart—and you can watch the full interview below).

For example, Trump’s disciples routinely call his comments in the wake of a neo-Nazi rally, in which he referred to “very fine people on both sides” a “hoax.” And they deny that he ever seriously suggested that injecting disinfectant might be a cure for covid-19. (Neither were hoaxes, as you probably viscerally recall).

This was an unbelievably consequential night for American history, which captures the ethos of Fluke beautifully. After telling jokes that may have solidified Trump’s ambition to run for president, Obama returned to the White House and oversaw the raid that killed Osama Bin Laden, just a few hours later. (The decision-making process he used is an example of radical uncertainty, a concept central to the arguments in Fluke).

Brian, I like your punchline…but how does one deliver honest criticism good naturedly?? I guess I have been around too many malignant narcissists in positions of power to even have that opportunity.

But there is a broader point to humor…it is a way of delivering truth and honesty about a variety of things we observe in life all the time. It is not just those in leadership positions, but societal groups writ large who need to stop taking themselves too seriously (a collective narcissism) also need that kind of feedback.

What would make your point even more compelling is to examine leaders who can take a joke, and/or have changed their path based on honest, constructive feedback. I fear in this day and age, they are few and far between as our individual and collective narcissism is growing and amplified in the world of social media that allows one to live in an echo chamber free of examination and criticism. Such that the role of humor and the jester is one of delivering to the message not to the leader, but to society at large to show the folly and insanity of it all. That is what made the Daily Show and Colbert so successful! Will it reach everybody? No. But others are increasingly using this tactic (political cartoonists are but one example).

Nice one, sir! We need the reminders and the analyses leavened with anecdote to reset after a week of diabolical and misleading nonsense - it saves us abandoning hope in these interesting times.