Why do dictators hold "elections"—but rig them?

This weekend, there was an "election-style event" in Russia. What's the rationale for such obvious sham contests? And how can we prove they were rigged?

Thank you for reading The Garden of Forking Paths. Part of this edition is for paid subscribers only. If you’d like to get full access to this and over 100 other articles, consider supporting my work by upgrading to a paid subscription for $4/month.

From Name Doubles to Body Doubles

In 2021, voters in St. Petersburg went to cast their ballots in a municipal “election.” One of the main opposition candidates was named Boris Vishnevsky, a hopeful from the liberal Yabloko party.

But when voters got their ballots, they noticed something a bit strange. The ballot paper, as was standard practice, showed photos of the candidates. On this ballot, however, there were three nearly identical photos of three nearly identical men, all named Boris Vishnevsky.

Russian election-style events have previously featured “name doubles,” in which the regime finds people to change their name to match the opposition candidate’s name. The idea is ruthlessly clever: voters won’t know which candidate is the “real” one, so the vote will be split, causing the actual opposition leader to lose.

But with photos now appearing on the ballot, the name double strategy wouldn’t work. This time, they needed to find people who already looked like the candidate, get them to modify their appearance, and change their name to match the opposition leader. That’s precisely what they did. One of the fake Borises even shaved his head to appear more believable. (Needless to say, it works).

The Rise of “Election-Style Events”

You may have heard that Russia held an election this weekend. That’s not true. Vladimir Putin organized an “election-style event,” which involves the same charade of campaigning and parade of voting as actual elections, but with one key difference: this was voting without democracy.

To highlight the point, the European Union Council president Charles Michel congratulated Putin on his victory before the election began.

This raises the obvious question: why bother? If you’re going to murder your opponents, silence your critics, and muzzle the press, why even allow people to vote? Surely that’s just inviting an opportunity for opposition to rally against you. Wouldn’t it be wiser to just rule with an iron fist—with bullets, not ballots?

During the Cold War, most dictators didn’t bother holding elections—or held one-party contests that didn’t allow opposition candidates on the ballot. These were the 99.9 percent landslides, where there wasn’t even a pretense of competition. They were vanity events, nothing more.

But after the Cold War ended, the United States—and US allies—became the only geopolitical game in town. Countries that wanted to be aligned with the global superpower (or avoid running afoul of a more democratic global political system) would have to at least go through the motions of holding plausibly competitive elections.

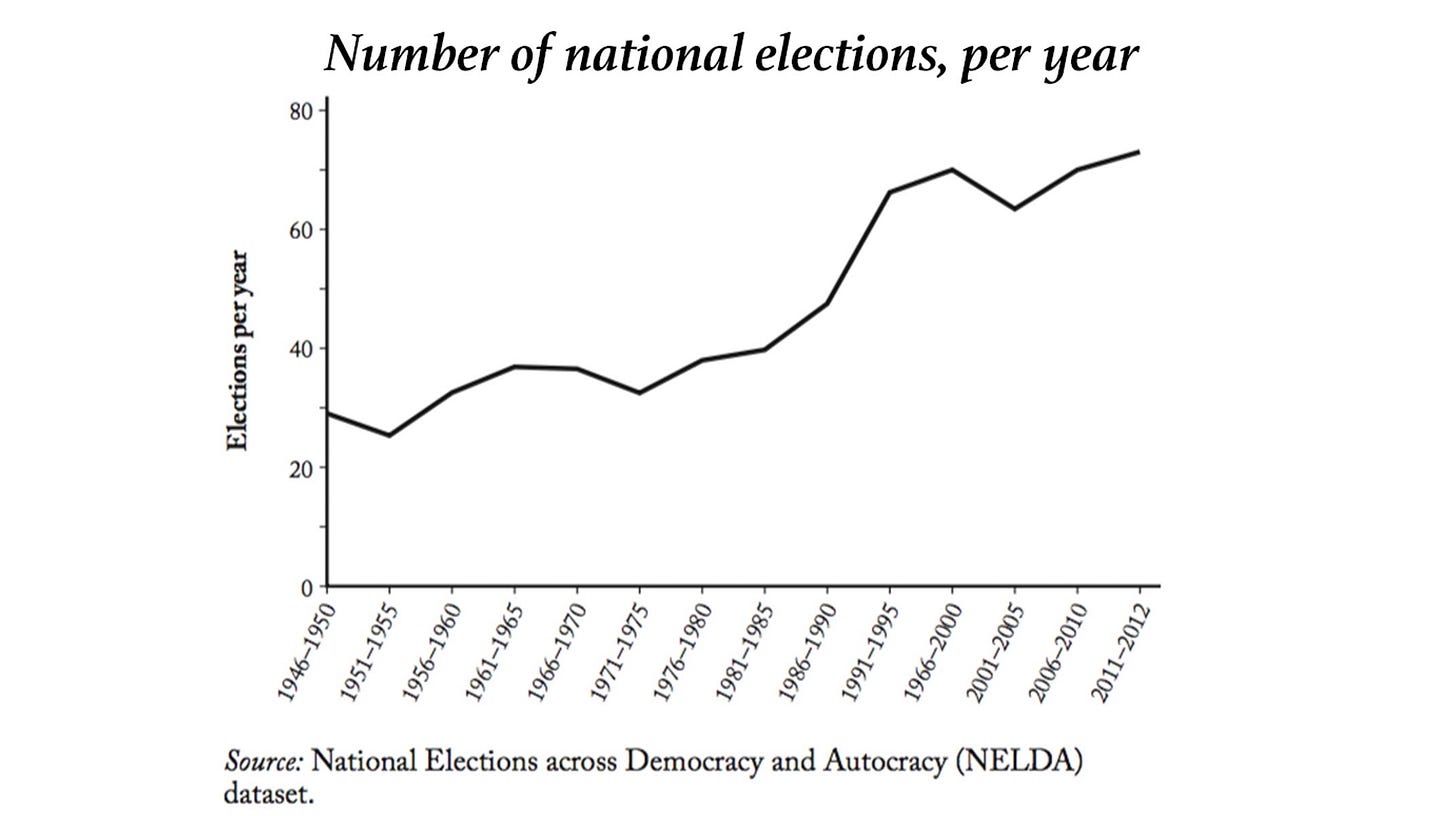

Almost overnight, a global norm emerged: hold an election, or become an international pariah. The graph below shows the surge in national elections per year, from 30 a year in the wake of World War II to nearly 80 per year, over a relatively short time period. (2024 is the “year of elections” given how many people live in countries that are holding elections this year).

But that didn’t mean that the authoritarian leaders would allow genuine competition. Instead, from the early 1990s to 2024, there has been a steady process of authoritarian learning, in which despots figure out the tricks of the trade—often by swapping strategies—in order to hold elections but rig them. That way, they ensure that nobody truly challenges their iron grip on power.

There is, however, a more interesting set of reasons for why dictators like Vladimir Putin hold “election-style events.” And once you realize what they are, you’ll understand that they’re not just being rational, but savvy.

Nonetheless, none of them are clever enough to fully get away with it, and, as we’ll see, there are new mathematical techniques that can help expose methods of rigging that previously went undetected.

Loyalty Tests and Information Gathering

In democracies, elections determine who governs. In dictatorships—as in Putin’s Russia—that’s never in doubt. Instead, one of the key functions of authoritarian election-style events is to determine who is loyal to the despot—and who’s a potential enemy of the state.

When dictatorships didn’t hold multi-party elections, as was widely the case during the Cold War, there was no clear-cut way for an autocrat to identify his adversaries.

However, when you open the space for political competition even a sliver, the most intense opponents of the regime will begin to speak out. These brave figures embolden some of their followers, who also become easy to identify as threats to the regime. In that way, then, election-style events are a rational mechanism for finding out who you need to worry about, allowing the intelligence services to incorporate a key mantra into their operations: better the devil you know.

Additionally, when it comes to gathering information, dictators are the victims of their own repression. Because citizens are afraid to say what they actually think, election-style events that allow some opposition can provide useful clues about the genuine views of the broader public.

This isn’t really the case in Russia, where public fear of expressing political viewpoints is so high that Putin won’t gain any real insights from this sham contest, but in some authoritarian regimes, election-style events are the only way that a despot can get reasonably accurate feedback about public attitudes toward the regime. (Polling is useless in these contexts, because nobody will answer a pollster truthfully, assuming it’s a trap set up by the regime).

Silencing the Opposition and “Shaking the Matchbox”

Even if everyone knows that the contest is a sham, it still serves a useful purpose domestically: making the opposition think twice about standing up to the dictator. Consider two electoral outcomes: in the first, the incumbent wins re-election, 53 percent to 47 percent. In the second, the incumbent wins 80 percent to 20 percent.

With the first ratio, the opposition will be galvanized: “we almost won!” In the second, plenty will give up. “Why bother?” This is especially true in authoritarian contexts where the risks of opposing the regime are literally life and death; it’s easier to risk your safety when there’s a perceived hope of success. Dictators exploit this dynamic, and sham elections—even ones that are clearly and blatantly manipulated—can send a clear message: resistance is futile so you might as well give up.

When the opposition is geographically concentrated, as is often the case, the authoritarian regime can also use elections to intimidate those opposition strongholds en masse. As Nic Cheeseman, my co-author of How to Rig an Election, noted, the Zimbabwean government burned down many homes in an area known to support the opposition candidate. The idea was to silence their opponents by intimidating them around the voting period.

However, because Zimbabwe’s arsonists attracted international coverage and condemnation, the regime innovated with a new strategy for the next election. This time, henchmen from the ruling party simply walked through the opposition area while shaking a matchbox, a haunting sound that reminded them—in not so subtle ways—that the arsonists could return if they didn’t toe the line.

But a man shaking a matchbox isn’t going to generate the same press coverage or diplomatic backlash as actually burning down houses; the regime had achieved the same goal of silencing the opposition, without any of the downsides.

Sinister, yes, but smart.

Fooling the Donors

Dictators who hold election-style events are also performing for an international audience. They can claim legitimacy, even if it’s obviously absurd.

Nobody is going to be fooled by Putin’s sham contest, but he will nonetheless claim—unashamedly—that he has a popular mandate from an election. This isn’t going to do much for Putin since he’s already an international pariah, but in many authoritarian regimes, the level of international scrutiny is much lower, so donors do either fall for it, or just set the bar so low that they accept the results of ridiculously bad elections that were blatantly manipulated.

Often, countries like the United States and United Kingdom aren’t actually fooled so much as they’re willing to just accept anything that fits their geopolitical agenda. If the dictator does the bare minimum of holding a vote to provide a fig leaf of plausible deniability, that’s sufficient.

For example, the United States government praised an election in Azerbaijan in which the dictator accidentally released the results the day before the election. But Azerbaijan has a lot of natural gas, so it wasn’t in the interest of US foreign policy to condemn the dictator and isolate him diplomatically. Having a vote—even a ridiculously rigged one—was deemed good enough.

Similarly, the British government is currently trying to hammer out the details of an appalling scheme to send migrants to Rwanda, which is under the control of a dictator who wins election-style events with margins of victory that would make Saddam Hussein proud. But because the dictator is officially “elected,” that can be used as a talking point to dupe those who are less informed about a tiny African nation, providing a convenient smokescreen for the British government to obscure the absurd immorality of their proposed scheme.

Often, the bare minimum is enough to fool—or at least placate—richer, more powerful countries in the geopolitical West.

Exposing Rigging by the Numbers

Now that we’ve covered a few rationales that provoke dictators into holding election-style events, let’s look at how we can catch them being rigged.

There are countless ways that election observers and researchers try to prove that electoral manipulation has taken place (and we outline many of them in How to Rig an Election). But here, I’d like to focus on the innovative, clever math that’s being used to catch the cheaters.

When election results are released with vote tallies down to the precinct level, there are tens of thousands of data points that give people like me the opportunity to crunch the numbers for any patterns that produce red flags. One pattern that recurs is the pattern of fewer round numbers, which is a telltale sign that the numbers have been made up, not produced by actual voters.

When someone is asked to pick a number between one and ten, the most common choice is 7. Our brains tend to think that “random” means “not round.” So, if we’re trying to generate plausible fake numbers that seem real, we wouldn’t tend to choose 50 or 100, or anything similarly neat and tidy.

The same is true of electoral henchmen. When they invent vote tallies, they systematically steer clear of numbers that end in “0” or “5” and often over-represent numbers that end in “3” and “7”. Using statistical analysis, it’s possible to determine whether an election has been rigged in the vote tallies simply by seeing those artefacts in the data, vestiges of our false belief that round numbers are bound to seem fake. It’s the opposite, in fact: an absence of round numbers is evidence of rigging.

However, in Russia, the pattern is a bit more complex—and fascinating. As I wrote in a recent piece for The Atlantic:

The researchers Dmitry Kobak, Sergey Shpilkin, and Maxim S. Pshenichnikov examined raw data produced by Putin’s sham contests and found dubious patterns that don’t show up in legitimate elections—specifically, the over-representation of pleasingly digestible round integers. Numbers such as 85.0 percent showed up in Russian election data more often than numbers such as 85.3 percent. In one study, this over-representation of whole numbers held true for every reported figure above 70 percent turnout and above 75 percent voting “yes” in one of Putin's fake referenda.

In other words, whenever the results were in landslide territory, there was strong evidence of tampering. In the graphic the researchers produced (below), a grid pattern starts to emerge in the upper right, showcasing the particular density of results around specific whole integers, a telltale sign of human manipulation.

Of course, the henchmen aren’t stupid enough to simply report a round number of 85.0 percent turnout. Instead, as the researchers explain, they use that figure as a target, and then might report something like 867 “yes” votes out of 1,020 cast. In isolation, these raw vote tallies seem perfectly ordinary—neither is a particularly round number. But if you calculate the proportion, it’s exactly 85.0 percent. By adding up all the percentages produced across the country, a systematic pattern of deliberate falsification emerges.

Here’s the data, so you can see for yourself. In the top right corner of the chart, you’ll see the outlines of very clear boxes. That’s because the density of the data is clustering around the integers—the ones that they’re targeting for their made up vote tallies.

Of course, we don’t have fresh data from this weekend’s election-style event in Russia yet, but I imagine it will follow the same patterns as before. Putin will continue to rig his election-style events in bold and blatant ways.

We too often make the mistake of applying the logic of our elections to these sham election-style events. But, for Putin, as with so many dictators, it doesn’t matter much that he’s been caught. He wasn’t really trying to fool us. Instead, the voting serves alternative purposes. And with him recently having killed Alexei Navalny before winning a landslide in the midst of a war, this is yet another savvy way for the Kremlin’s tyrant to assert his dominance over a political system that is defined by fear, control, violence, and repression. That’s why, no matter what, we shouldn’t give him the satisfaction of calling what just happened an “election.”

Thank you for reading The Garden of Forking Paths. Most of this article was for paid subscribers only, so thank you for supporting my work. You make it possible. As always, you can read more of my writing in my new book, FLUKE—and if you’ve already read it, please rate and review it on Amazon or Goodreads, as those reviews really do help a book take off.