We need sting operations for politicians

Corruption, lobbying, and improper political influence plague our political systems, wasting money and creating bad governance. We should start using randomized sting operations to expose corruption.

Thank you for reading The Garden of Forking Paths. This article is free, so please share it. If you’d like to support my work, rather than supporting yet another large, faceless multinational media conglomerate, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription. You get access to twice as many articles and can debate and discuss these articles without trolls.

Integrity testing and the power of randomness

Picture this: an officer with the NYPD gets called to a crime scene. “You’re the first to arrive there,” he’s told by the dispatcher. “Don’t touch anything. We just need you to babysit the location, to secure it, until the main team of investigators arrive.”

All he needs to do is go inside and sit tight. No brain cells required.

He walks up the stairs to the crime scene and finds 20 grand of cash sitting on the table, along with a few bags of cocaine, waiting to be packaged for sale. Nobody from law enforcement has been there before, so nobody knows what’s supposed to be there and what isn’t. Looking around to make sure nobody’s watching, the cop pockets $6,000.

“My bosses will be happy enough that I’ve recovered $14,000,” he tells himself. “And nobody will ever know about the rest.”

Except there’s one problem. The “crime scene” is a set-up. It’s a sting operation, an elaborately developed test — and this officer just failed it badly. The cash was real, but the drug dealers weren’t. Too bad for him. He was stupid enough to take the bait. Internal affairs just reeled in a crooked cop.

This scenario plays out regularly in police forces that use integrity tests. It involves randomized oversight of police officers, testing them to see if they behave with integrity when opportunity arises for them to break the law by stealing money or abusing suspected criminals.

I learned about these tests when I interviewed Charles Campisi, the former head of internal affairs with the NYPD. His innovation helped catch and expose police malfeasance. By randomly testing his officers, every officer knew that any crime scene could be a set-up.

That led to an amazing, ingenious twist that showcases the power of randomness.

In 2012, Campisi organized 530 integrity tests across the NYPD. But when a researcher surveyed the police force, more than 6,000 cops said they believed they had been tested. More than 90 percent of those were false positives, real crime scenes that the police officers believed were faked, simply to test them.

As I wrote in my last book, “Corruptible":

The remainder of the force knew they could be under surveillance at any moment. Any drugs bust or routine traffic stop could be an elaborate test. With that healthy dose of fear, fewer officers skimmed cash or stole drugs or beat up insolent criminals.

The lesson here isn’t to start baiting employees by planting pieces of cake in the break-room fridge with enough hidden cameras to catch the person who snatches it…But people who are in uniquely consequential positions of authority [should] worry about being watched.

But it got me thinking. Why do we have integrity tests for police officers but not for politicians? Why do we try to sting run-of-the-mill power holders like beat cops, but do nothing similar for catching corruption in far more consequential roles at the top of our societies? The answer is staring us in the face: we should do exactly that. And we should start doing it…right now.

Legalized corruption?

Lobbying, to a certain extent, is legalized corruption. However, there are some key differences. For example, political science research has demonstrated that political corruption doesn’t work very well to achieve results; plenty of people who try to grease the wheels in developing countries come up empty, failing to influence policymaking to their advantage. By contrast, lobbying in rich democracies often works really well.

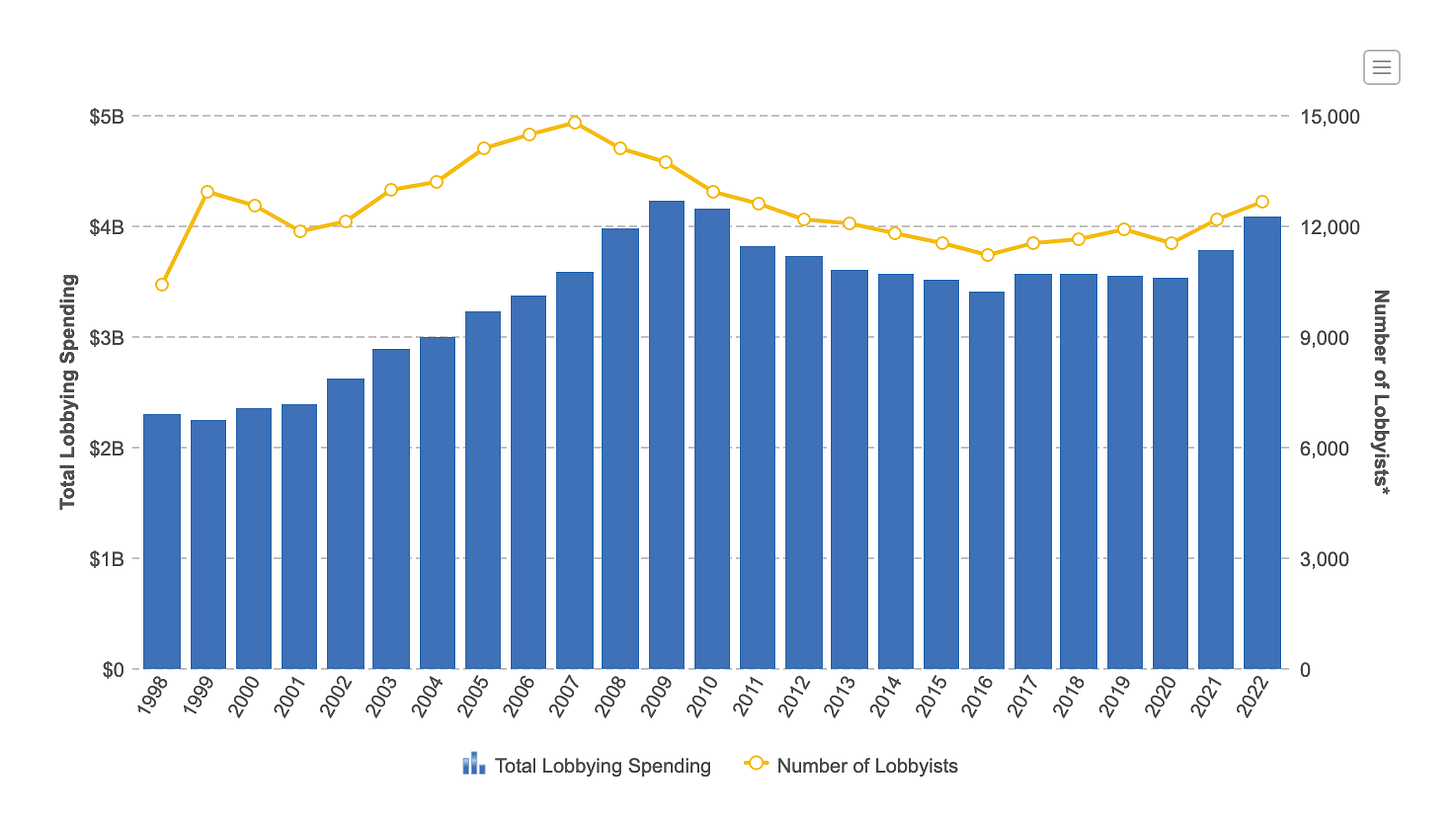

In fact, one study from the United States found that some firms received an unbelievable return on their lobbying investment, making about $220 more for every $1 they spent on lobbying. (Other studies haven’t produced quite such astonishing numbers, but one meta-analysis of lobbying studies showed most researchers agreed that businesses that lobby politicians do a lot better in terms of performance, suggesting that political influence is a solid pathway to profits).

It’s a huge business. According to Open Secrets, a political spending watchdog group, there are about 12,000 lobbyists working in the US. Last year, lobbying consumed more than $4 billion. Here’s the data over time from Open Secrets, adjusted for inflation.

The covid-19 spending bananza

One of the most egregious examples of political malfeasance and corruption through lobbying came during the covid-19 government spending bonanzas. In the United States, hundreds of billions of dollars were lost or wasted due to fraud or criminality.

But it’s the United Kingdom that offers the clearest example of the kind of political activity that could be tackled with an NYPD-style integrity test, a sting operation to expose the crooked politicians and make them fear the costs of corruption.

When Boris Johnson’s Tory government was giving out health-related contracts like candy in 2020, there was very little oversight. That made some sense. After all, there was an unprecedented public health emergency happening. Nobody knew what to do. And the worst thing would have been for masks and other protective equipment for health care workers to get delayed by bureaucratic red tape.

However, without oversight, a lot of corruption and fraud took place. Between 5 billion and 8 billion pounds were wasted. But even more alarmingly, the government handed out a huge number of contracts to unqualified firms that were run by the friends of elected officials.

Transparency International estimates that one-fifth of the value of those contracts were awarded in suspect ways, suggesting that political connections, not merit, led to government money being awarded. Many of those contracts were fast-tracked through what was called a “VIP” or “high-priority lane” for politically-connected firms.

Surprise, surprise: the companies that were put in the VIP lane had a much better chance of being awarded contracts than the ones that didn’t. This graphic from The Guardian shows just how big of a difference there was:

In one instance, as The Guardian reported, a local Tory activist approached Greg Hands — an MP who now is the chairman of the Conservative party. Soon, a firm called Luxe Lifestyle, which had never supplied personal protective equipment, was given nearly £26 millon ($31.2 million) from the government. Countless contracts followed the same ridiculous pathway. It was blatant, absurd, hopeless corruption — and it damaged public health.

People surely died because of it.

What could have put a stop to this? The answer, I suspect, lies with Campisi’s integrity tests. Let me explain how it would work for politics instead of police.

A modest proposal: sting the politicians

Journalists regularly try to expose politicians who behave badly. But what they don’t do is to try to test the system and see if they can sting a politician into crossing a line they shouldn’t.

Imagine this scenario: an elected official gets introduced to a new “friend” from an activist in his or her local constituency. This friend has a business in the local community — and they’re angling for a government contract.

Even better, the company has enlisted the help of a slick lobbyist to help make their case. Over a glass of wine, or a fancy dinner, the lobbyist gives a polished pitch. Sure, the company might not win the bid through a competitive process, but maybe there’s another way. Perhaps the politician can make some calls, pull a few strings, call in some favors.

In the end: ka-ching! The company gets told it will get the government contract.

And then comes the big reveal. The company is fake. The “lobbyist” is an undercover journalist. The whole thing was a test. And the politician just failed it. All that needs to happen next is for the newspaper that orchestrated the whole thing to write up the story, making clear that with the right connections, that political figure can be bought for a pretty low price.

But here’s the beauty of this idea: you just need to do this once. As soon as just one prospective government contract is revealed to actually be a sting operation, all of them could be a set-up. And that would make politicians scared to engage in corruption — as they should be.

That’s the power of randomized oversight.

Of course, there are legal considerations that could block this tactic in some jurisdictions. But some version of it would be possible most places. And given the vast scale of corruption and, as the British call it, chum-ocracy, something needs to be done. My modest proposal is that if we’re using random oversight to test cops, then why shouldn’t we do the same with the people who run our societies?

Sting operations aren’t nice. They’re dishonest and deceptive. But there are a lot of dishonest people in power who are decieving all of us — right now. And the consequences of their deceptions are wasting billions in taxpayer dollars while making government fail to deliver good governance.

It’s time that the people in Congress or Parliament start to fear that maybe, just maybe, it’s them, not us, who is being set-up.

Thank you for reading. If you’ve enjoyed this article, please consider sharing it, or better yet, upgrading to a paid subscription. Half of the content for the newsletter is for paid subscribers only, and I rely exclusively on your support to produce these articles.

Great article!

Brian, great stuff as always! Your punch line about stings being inherently dishonest and sneaky is not the point. Those being “stung” play victim saying that it was all a set up and they should not be held accountable. The point is one needs to fight fire with fire. Corruption and the fight against it is inherently an asymmetric game/battle. Those engaging in corruption have no rules, yet those fighting it must follow rules.

What you are proposing is to even the playing field. As an economist by training, using this game theoretic approach makes sense and should be implemented widely across not just those in authority such as police and politicians but also across other sectors of the economy at upper management and C-suites.

BTW, what you propose has been around in the economic literature for at least 3 decades to enforce rules (say environmental laws and regard in which I was interested at the time). The idea is random, unannounced monitoring helped enforce such regimes across the board where direct monitoring across all sites is impractical for technical or cost reasons.

The same principles apply to rooting out corruption. But unfortunately, when the corrupt and ideologically homogenous groups control the levers of power, such methods are used to crush dissent, ideas, and the free flow of information such as in authoritarian regimes. Spies and informants are everywhere and you do not know who they are.