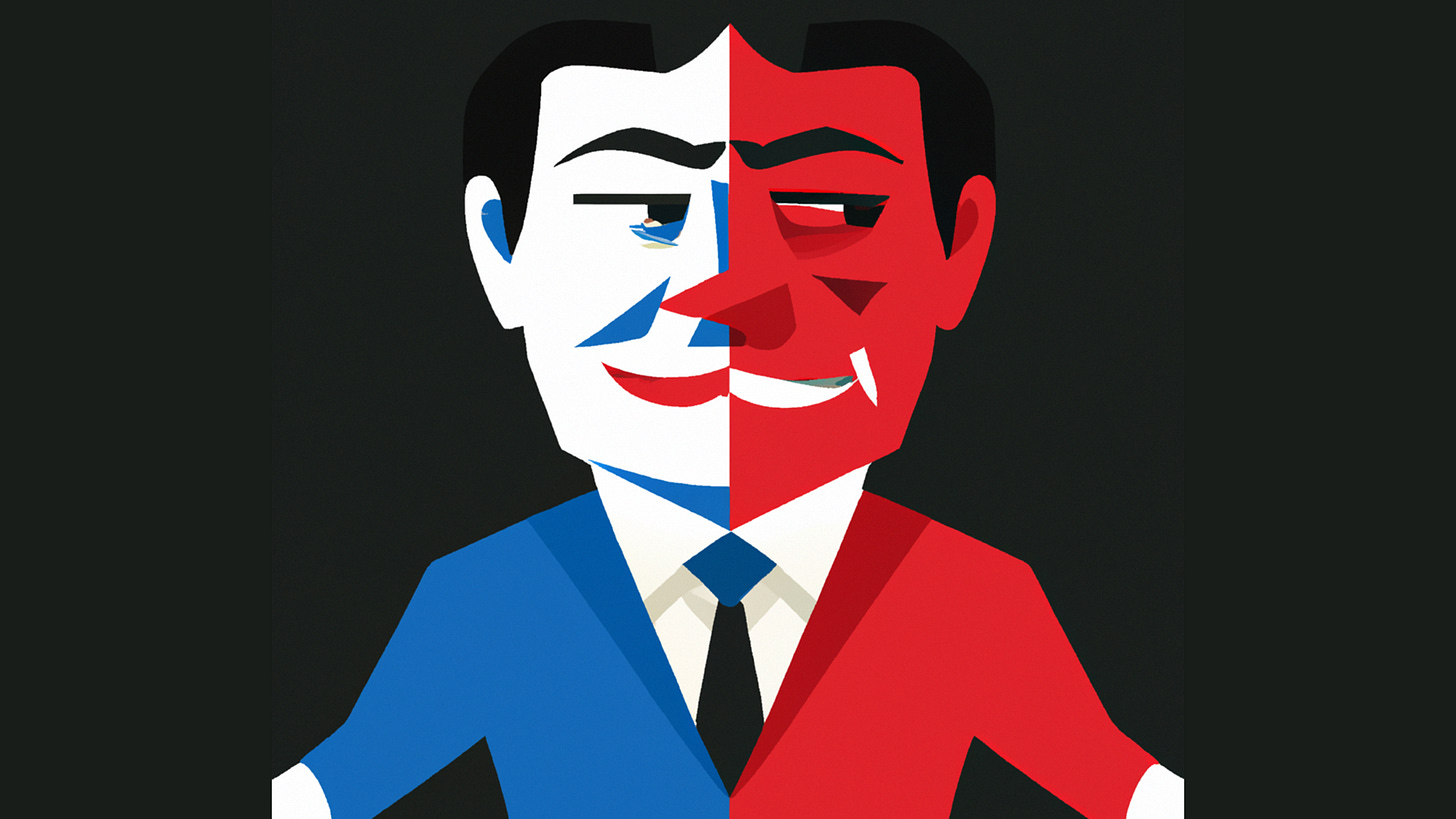

Treat Politicians Like the Rest of Us

Why do we hold ordinary corporate employees to a higher standard than members of Congress? We've created a "broken pyramid of scrutiny," in which we monitor and scrutinize the least powerful the most.

If you’ve enjoyed my writing, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. This newsletter is a reader-supported publication, and it costs the same as just one latte per month. You’ll get access to double the content compared to free subscribers.

Why do we hold ordinary corporate employees to a much higher standard than members of Congress?

This isn’t hyperbole. Routinely, elected officials in Congress—the 535 people who are supposed to be the best representatives of 330 million Americans—face zero consequences for behavior that would get them immediately fired from any job with a functioning HR department.

We often hear meaningless bromides about how elected officials hold themselves to a higher standard. But any objective assessment of political history shows the opposite is true. Corporate and government employees face far more professional scrutiny and accountability than the people who are, at least in theory, supposed to be our moral exemplars. (This holds true in a wide variety of democracies, not just the United States).

The recently elected New York Congressman George Santos is a case in point. His CV is, I’ll admit, impressive. Single-handedly blocked the metric system. Enlisted without hesitation after Pearl Harbor. Discovered Atlantis. Destroyed the Ring of Power in Mordor. It’s a great résumé.

But in all seriousness, Santos (if that is his real name) has concocted a false identity filled with more whoppers than your average Burger King.

These were not white lies, either.

Santos lied about having a college degree, claimed he ran an animal rescue group that doesn’t exist, lamented that his invented employees were murdered in the Pulse nightclub massacre, fabricated his entire employment history, claimed that his mother died on two different occasions (including once on 9/11), and variously claimed to be Black and Jewish. (Santos has since clarified that he meant that he was “Jew-ish,” giving him the honor of committing one of most grotesquely inept attempts at damage control in modern American political history).

Anyone in a corporate job—from a lowly paper pusher to a senior executive—would be immediately fired if they were caught lying on their CV. And with good reason.

Instead, Santos will face a lengthy, drawn out process that may or may not result in direct consequences. How is it possible that an administrative employee tasked with photocopying at, say, General Motors would be fired faster for the same transgressions than a member of the top elected body in the most powerful democracy in the world?

Much of the modern world has created what I call the broken pyramid of scrutiny. In principle, levels of scrutiny and accountability should increase as the potential to do catastrophic harm increases. The higher up the hierarchy you go, the more that you should be monitored to make sure that you’re not going to destroy the company, or bring down the government, from your perch at the top. The least powerful should face the least scrutiny; the most powerful the most oversight.

Instead, as I wrote in “Corruptible,” we do the opposite.

As power—and the power to do catastrophic harm—increases, mandatory levels of scrutiny, monitoring, and oversight decrease. Scrutiny in the modern era looks like a pyramid: the higher you go, the less there is.

In my spare time, I volunteer as a tour guide at a historic site in England. To be allowed to take tours, I had to spend six months learning about the site, pass two exams, spend hours clicking through a series of online training courses, and complete some checks regarding safeguarding.

And yet, there are literally zero requirements, zero checks, zero bits of required training for the US president, even though they are given control not of a tour group, but of enough nuclear weapons to kill all eight billion of us. (The same lack of requirements is true for members of Congress).

Put bluntly, there are more formal training and oversight requirements to become a volunteer tour guide than to become a member of Congress. Why do we accept that?

The same is true for powerful people in different contexts. We monitor employees, not executives. It’s become even more dystopian since the pandemic and the rise of working from home, as computers are monitored, prompting employees to try to find ways to make their mouses and keyboards move when they’re away from their computers so they appear to be working when they take a bathroom break. Some companies have even started using chair sensors, to monitor whether an employee is seated at their desk as they claim. To bypass it, you need to find a weight equal to a human and plop it down in your stead.

The broken pyramid of scrutiny is even built into the architecture of our office spaces, in which the lowly masses sit in open plan offices where they can be watched, while CEOs and other senior officials sit behind opaque windows in corner offices.

This makes no sense.

Enron wasn’t taken down by employees stealing paper clips or taking extra long lunch breaks. It was taken down by powerful conmen at the top who knew exactly what they were doing—and got away with it because nobody could hold them accountable. Likewise, despite being in charge of billions of dollars, Sam Bankman-Fried of FTX was subject to, it appears, zero oversight. But could he have monitored his employees? Absolutely.

One recent estimate by Eugene Soltes of Harvard suggests that white collar crime accounts for roughly $250 billion to $400 billion in losses or damages in the US each year, compared to $17 billion lost due to all property crime combined (burglaries, robberies, thefts, and arson). We’re watching the wrong people.

Japan, in its wisdom, has an appropriate architectural mentality for organizing office spaces. The people who become irrelevant through incompetence are pushed to the edges, while the important employees are more centrally located. The obscure periphery where nobody watches you is reserved for the undesirables. As I wrote in “Corruptible”:

Japan provides an interesting example of reorienting a worker’s physical space based on who can actually do damage in a company. Incompetent workers aren’t fired in Japanese corporate culture, but rather become known as madogiwa-zoku, “window watchers.” That’s because they’re moved to the periphery of the office. As they’re demoted to work on insignificant projects, they can look out the window, as nobody need even bother watching them

And yet, we continue to make the same mistakes with our broken pyramids of scrutiny. Government employees—even for relatively unimportant jobs—are often subject to background checks. Anyone, no matter how junior, who has to handle sensitive information must go through a rigorous process to get a security clearance. That’s a good thing.

But for Members of Congress who get access to the most closely guarded secrets the nation has, there’s no such process. George Santos would likely have been exposed as a fraud before getting just about any run-of-the-mill government job (and certainly one that required a security clearance), but he wasn’t exposed before getting elected to Congress. It’s completely backwards. What are we thinking?

The craziest aspect is that a security clearance is not rare in America. An estimated 2.8 million Americans have a security clearance, and over a million of those people have access to Top Secret information. And yet we don’t demand this of 535 people who are elected to lead the country, or the president, or the Supreme Court?

We just assume it’ll be fine and hope for the best.

This failed model of trusting politicians without any sort of verification is also becoming utterly untenable given that Republicans are now routinely electing deranged authoritarian zealots like Marjorie Taylor Greene, who believe in QAnon and denounce Jewish Space Lasers (or were they just “Jew-ish”?). How many members of Congress would fail a routine background check or extensive verification process to give them security clearance? The answer, I suspect, would be unsettling.

Why don’t we have mandatory background checks for members of Congress? Why are members of Congress not subject to the same security clearance checks as anyone else who’s handling sensitive information?

There are, admittedly, tricky logistical questions to resolve within these questions. Should these checks be conducted during the candidate selection process in the primary rather than after they win and voters are stuck with them? What should the consequences be for a failed background check? These are challenging questions, but they’re not insurmountable—and any answers we came up with as a society would be superior to doing literally nothing.

And then, there’s the question of training. If you’re an employee of a company, odds are good that you’ve been forced to undergo mandatory training, often with an exam at the end to test your knowledge. Why do we exempt the people who make decisions about our lives from any mandatory training? Why shouldn’t they be forced to demonstrate at least the most rudimentary knowledge of systems that they’re controlling?

How is it possible that, for years, Donald Trump thought that NATO was a fund that countries paid into, rather than a military alliance in which member states pledged to spend two percent of their GDP on defense? Does anyone believe that Donald Trump had even a rough idea of how America’s health care system actually works? How about Lauren Boebert or Louie Gohmert?

It would need not be a “gotcha” aspect of our politics to score points against ignorant fools, but rather a fact-based training protocol conducted behind closed doors that must be passed before someone can cast a vote in Congress.

We’d all be better off if our elected officials actually understood the government they were trying to run. That, I fear, is not currently the case.

Instead, it’s like a game of political limbo, in which we continually lower the bar. The rest of us have to contort ourselves to go under it, to clear it, but politicians just hop right over that incredibly low bar without a care in the world.

Why don’t all politicians naturally become walking encyclopedias and seek out policy training themselves? Because that’s not what we reward. To maintain power, politicians don’t need to know the budget of the Department of Energy; they need to raise money, generate press, and wallop their opponents with negative ads. The sad truth is that for most politicians in modern American politics, spending time on understanding policy problems is, at least from an electoral perspective, time wasted.

When I worked as an intern in the US Senate many years ago, I realized that young staffers often understand the minutiae of government far better than the politicians, who spend much of their waking hours on tactics, talking points, media interviews, and, most of all, “call time” to raise money from donors.

We’ve built a system that attracts and rewards people who seek power, not to solve problems. George Santos is just one inevitable result of such a system.

It will be hard to transform our electorate into one that rewards effective policy wonks more than demagogues, but that’s the long term solution. In the meantime, it’s far easier to reform our political system by adopting oversight and training requirements that follow a principle that’s as simple as it is elegant: treat politicians like the rest of us.

If you’ve enjoyed this article, or any of my work, please consider subscribing. You can sign-up for free, or you can support my work by becoming a paid subscriber, which will give you access to twice as many articles beamed into your inbox—all for the price of one latte per month. The Garden of Forking Paths is a reader supported newsletter.

And, if you’re a paid subscriber, I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments as to what sort of training, qualifications, exams, or oversight should be made mandatory for politicians in your country.

For further reading, I recommend:

Why They Do It, by Eugene Soltes on white collar crime and, if you’re interested in the sociology of being watched, Big Gods by Ara Norenzayan.

Happy new year! Thank you for airing an inequity that is so basic, yet so unexplored by more mainstream outlets. I’m currently job hunting (laid-off tech worker), and I spend ridiculous amounts of time correcting resume-slurping job app software that tries to turn my “BA studies in... “ qualification into “BA in ...” because I’m not trying to claim that I graduated.

This government was founded under the assumption that people of honor would rise to the most powerful positions. Instead we’ve got “Lies, and the Lying Liars Who Tell Them.”

You speak the ugly truth. The powerful write the rules and we plebians suffer. I find it infuriating to acknowledge our pyramid of scrutiny, yet we're all so busy trying to make a living that mobilizing for change is a mirage as the masses don't/won't engage. I can post a picture of my dogs on social media and get 100 likes, but if I post your excellent, on-point article only 5 people will "like" it and fewer will comment. It's exhausting to attempt to get others to join the call for change. So where's our MLK for common sense in workplaces and government?