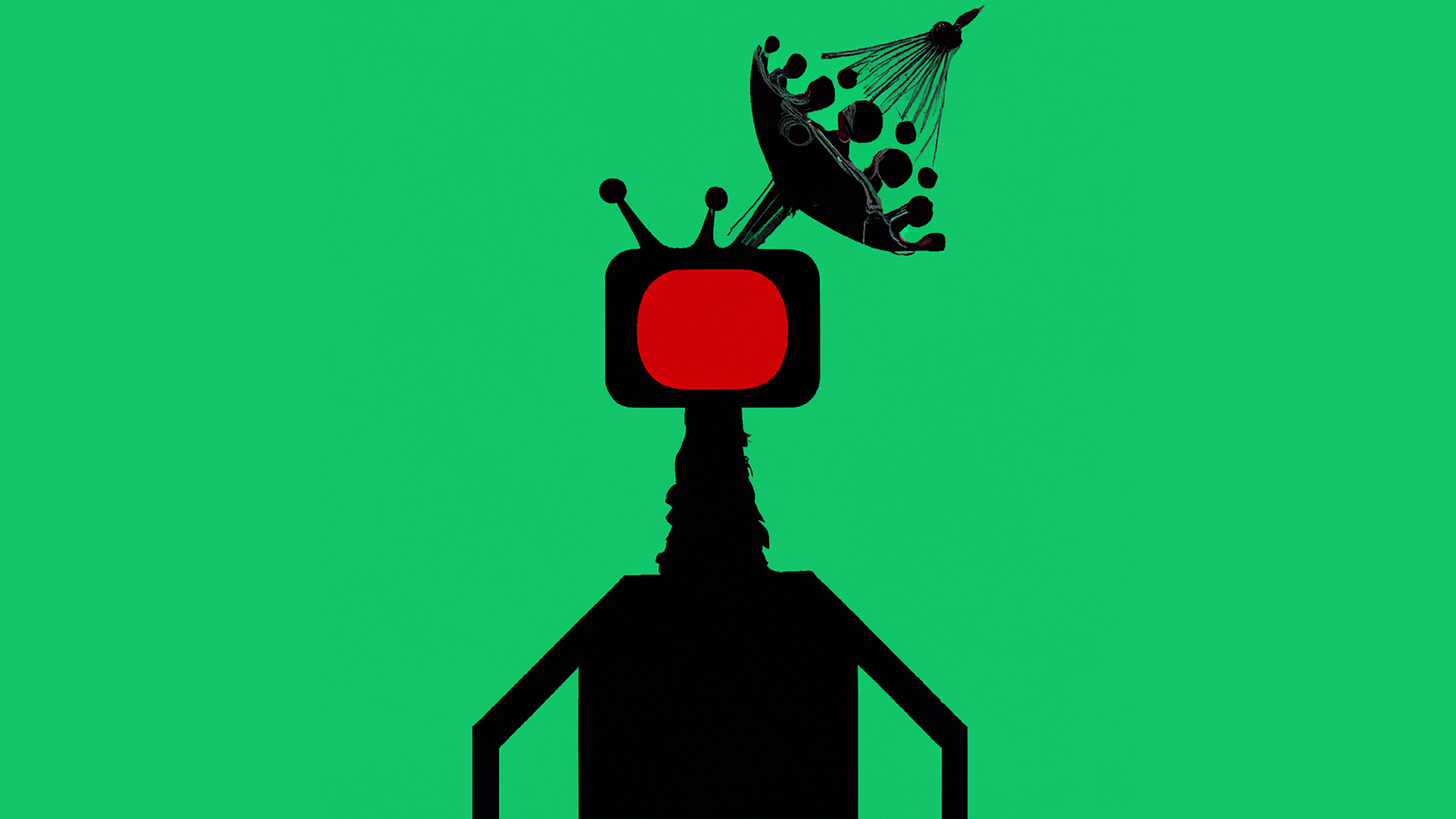

To Break Democracy, Break Information Flows

What does it mean to be a democracy in which citizens no longer have a shared sense of reality? I explore that with a forgotten saga of TV history involving Vrillon, an alien who warned of "untruths."

If you’re familiar with my work, you’ll know I have a soft spot for bizarre stories that convey important lessons. Today’s post is no exception.

This is a story about aliens, broadcasting, the reliability of information, and threats to democracy. It starts with a strange, forgotten footnote from British television history, but one that provides a nice entry point into discussing how important it is that citizens can trust what they hear about the world.

Forty-five years ago, tomorrow, something unusual happened in southern England. It was November 26, 1977, and the nightly news was covering violent clashes in Rhodesia (modern day Zimbabwe). Suddenly, without warning, the picture on the TV went fuzzy, before being replaced by a buzzing sound.

For the next six minutes, viewers listened, perplexed, as a distorted, electronic voice began to speak to them. “This is the voice of Vrillon,” the voice began. “A representative of the Ashtar Galactic Command, speaking to you.” It urged viewers to pay careful attention to what is truth, and what is “confusion, chaos, and untruth.” The transmission ended with a kind note.

“May you be blessed by the supreme love and truth of the cosmos.”

The phones of Southern Television started ringing off the hook. Viewers wanted answers, and the broadcast company didn’t have them. Hundreds of people reportedly called seeking reassurance that an alien invasion wasn’t imminent. Vrillon made headlines in international media.

The official line, of course, was that it was a hoax, caused by some technical wizardry. But not everyone was certain. In a letter to The Times two days after the broadcast, a concerned citizen wondered: how could the authorities “or anyone else – be sure that the broadcast was a hoax?” The incident became a favorite for proponents of UFOs, recorded proof of intelligent life out there. Heck, these were no simpletons. They even had a Galactic Command.

In the last forty-five years, nobody has come forward to take responsibility for Vrillon.

However, there is an explanation for how it happened. A broadcast transmitter in Hannington, a village in Hampshire, had been hijacked. At the time, the signal was weak enough that someone nearby could simply beam their broadcast at the tower, and it would overpower the official signal. Presumably, the hoaxer simply wandered up to the Hannington tower, and had a bit of fun.

Vrillon’s message was right about one thing, though: citizens need to be vigilant in sorting out what is truth from what is, as he put it with an Orwellian flourish, “untruth.”

In the modern era, we’ve grown used to hacking, not of broadcast TV signals perhaps, but of social media accounts. We’ve also, by necessity, become more accustomed to false information spreading through seemingly official channels.

In recent weeks, the problem has become more acute, as Elon Musk’s hare-brained scheme to sell official looking blue check marks on Twitter led to a series of fake tweets going viral, with millions of people duped and billions of dollars of value lost. But even before Musk’s scheme blew up catastrophically, we’ve seen examples of false information sparking real world violence, from a QAnon disciple trying to blow up the Hoover Dam to fake tweets during Hurricane Sandy.

There’s a much larger lesson here and it is this: if you break the reliable flow of information to citizens, you break democracy. It’s that simple.

It’s quite clear that in many modern democracies, the information flow has broken. The United States is the most egregious example, and it’s one of the reason why I’m pessimistic that America can turn around its lurch toward authoritarianism, at least in the short-term.

At its core, democracy is a system aimed at forging compromise through informed consent of the governed. In other words, the chief mission of democratic institutions is to create a forum for engaged citizens to debate and discuss problems, find common ground, enact solutions, and do so with the informed approval of the citizenry writ large. But if you don’t have accurate information about what’s going on in the world, you can’t properly consent to what the government is doing.

Everything in democracy therefore relies on two core assumptions: that citizens have a shared sense of reality, and that they agree that a problem exists, because otherwise it’s futile to have a debate about how to fix it. Neither of those assumptions currently holds true in the United States, and, to a lesser extent, in a few other dysfunctional rich democracies.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Garden of Forking Paths to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.