The Rise of Granfalloon Politics

Why humans, more than ever before, are aligning themselves into meaningless groups that hate each other.

Thank you for reading The Garden of Forking Paths. If you think my writing adds value to your life, please consider supporting my work by upgrading to a paid subscription, like a modern Medici, a patron of the written arts. Unlike the Medicis, it costs about $1 per week.

The Granfalloon vs. the Karass

Cat’s Cradle, by Kurt Vonnegut, is my favorite novel. It’s a strange book, laced with playful, but profound insights. One example is the distinction that Vonnegut draws between what he calls a granfalloon and a karass, made up terminology for a fictional religion called Bokononism—founded by an invented island prophet named Bokonon.

Vonnegut’s whimsical distinction offers a useful framework for understanding modern social life—and the political dysfunction that we so often lazily group under the one-size-fits-all umbrella term: polarization.

A karass is a group of people brought together, often by chance, but stuck together by choice because they are truly like-minded souls. As Vonnegut writes: “If you find your life tangled up with somebody else's life for no very logical reason, that person may be a member of your karass.”

But crucially, these groupings are based on individuals as our authentic selves, the people we really are, the things we really care about, not necessarily the groupings that so often dominate our social lives. A true karass, Vonnegut writes “ignores national, institutional, occupational, familial, and class boundaries. It is as free form as an amoeba.”

By contrast, much of modern life is organized according to a “false karass, of a seeming team that was meaningless…a textbook example of what Bokonon calls a granfalloon. Other examples are the Communist party, the Daughters of the American Revolution, the General Electric Company, the International Order of Odd Fellows - and any nation, anytime, anywhere.”

The crucial component of a granfalloon is that its members think that the association between people means something, but in reality, it’s a meaningless group, driven by the absurdities of tribalism rather than anything deep, profound, or significant.

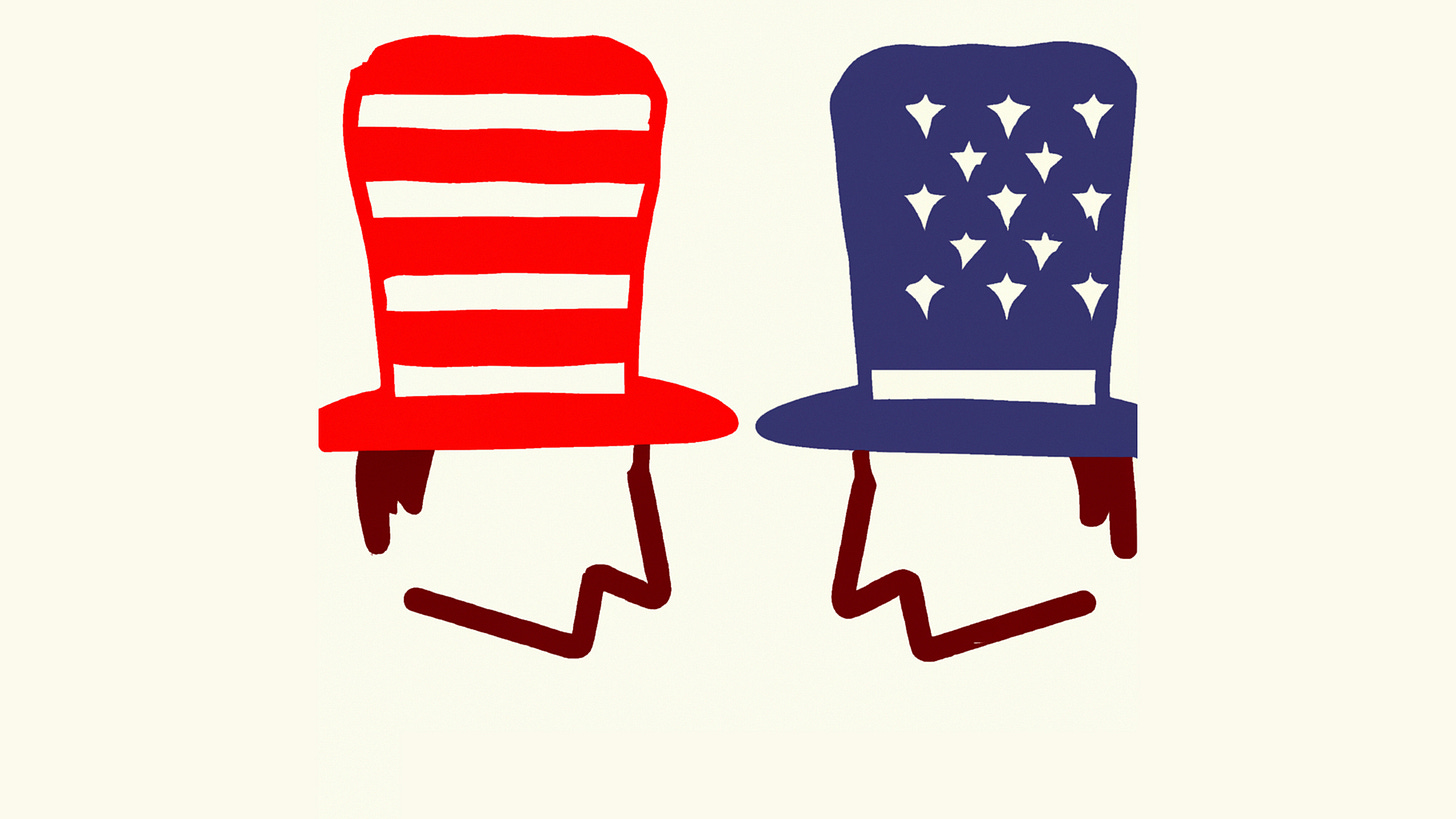

Now, consider modern politics through the lens of the karass and the granfalloon. Do we arrange ourselves according to our true passions with like-minded souls? Or do we use shortcuts and labels to put ourselves onto invented, angry teams that hate each other?

Of course, sometimes these signaling shortcuts are useful: I’m not particularly likely to develop a lasting, close, intellectual friendship with a person who wears a red MAGA hat and wears an InfoWars t-shirt. There are real differences in values between people who sort themselves into political groups.

But too often, we’re succumbing to an outdated evolutionary instinct to partition ourselves into arbitrary and meaningless cohorts. And we do it in some pretty absurd ways.

The Lure of the Granfalloon and Coin Toss Cults

Before World War II, a Polish Jew named Henri Tajfel (born as Hersz Mordche) moved to France to study chemistry, since Jews weren’t allowed into higher education back home. When the war broke out, he volunteered to fight with the French military, but ended up being captured by the Germans.

Tajfel realized that his fate hinged on his identity: if he admitted he was Jewish, he might be sent to a concentration camp rather than being treated as a prisoner-of-war. But if his captors found out later that he had lied about his identity, he knew, with certainty, that he would be killed. Tajfel kept the secret—and survived. When the war ended, he realized with considerable horror that his entire family, and most of his friends, had been killed.

Tajfel’s personal nightmare diverted his trajectory, from an abiding interest in chemistry to one in social psychology and group dynamics. He later became a titan of the field, after moving to the UK and taking up professorships at, to name a few, Oxford and the University of Bristol.

As part of his research, he concocted an ingenious study. Participants were told to watch a coin toss. If the coin landed heads, then the group watching would be designated as part of the Heads Group. If the coin landed tails, the group would be sorted into the Tails Group. The sorting was repeated over and over, until large groups formed.

In Tajfel’s studies, participants who were randomly assigned to a group still exhibited clear and consistent in-group favoritism, meaning that they would prioritize helping someone from their own group over someone from the other group, even when there was no rational basis for their association.

Humans, it turns out, are willing—even eager—to embrace arbitrary teams on the basis of the most ridiculous factors, simply because that means we’re part of a team. And once we’re grouped together, we vehemently identify with that group, even when we must know it’s absurd.

This gave rise to Tajfel’s discovery of what is now known as the Minimal Group Paradigm. The minimal conditions required for discrimination to occur between groups are really, really minor. Even a random coin toss can trigger it.

This Granfalloon might just save your life

In my last book, Corruptible, I point to some particularly jarring research that shows that we’ll even provide medical assistance to people on the basis of a textbook example of a granfalloon: being fans of the same sports team.

In one experiment, researchers in Britain recruited football (soccer) fans for a psychology experiment. Everyone who wasn’t a Manchester United fan was screened out of the participant pool, but participants didn’t know that’s why they’d been selected…The real experiment happened as participants moved from the first building to the second. Each person would encounter someone (an undercover member of the research team) who was visibly injured and needed assistance.

A third of the time, the supposedly injured person was wearing a Manchester United jersey. A third of the time, the person was wearing the jersey from Liverpool, a rival team. And a third of the time, the injured person was wearing a neutral shirt. The participants stopped to help those wearing Manchester United jerseys a whopping 92 percent of the time, compared to 35 percent for someone in a neutral shirt and just 30 percent for those wearing a rival-team shirt. The rates of assistance tripled, based only on a logo.

Now, I’m a diehard fan of the Minnesota Twins and the Minnesota Vikings, and I’ll admit that I’ll stop and say hello to people in foreign countries if they’re wearing one of those hats. And when I was a teenager, I despised our high school’s rival team, for no particularly good reason. But it’s objectively absurd that many of us behave so differently—even in moments of obvious need—depending on logos, sports affiliations, even school districts.

The same can be true, as Vonnegut highlights, with nationality. Having lived abroad for nearly twelve years, I’ve realized that I’m likely to have a lot more in common when I meet someone through a shared passion than on the arbitrary basis of our birth location. It’s pretty obvious I’d hit it off better with a Chilean who also loves the novel Cat’s Cradle than a Ku Klux Klan member from rural Alabama who has the same passport.

Nationality can therefore be an example of what Benedict Anderson called an “Imagined Community.” And yet, nationalism is one of the most potent forces in human culture, as Henri Tajfel tragically found out.

So there you have it: we’re a granfalloon species, through and through. Why is that?

The Evolution of the Granfalloon

We are animals, though we often forget it. And like other animals, we need to feed ourselves to survive—while not becoming food for another predator.

That simple fact provides a strong incentive for individuals to form into groups. Just as with shoals of fish, or herds of animals, the evolutionary past of hominins (the subset of primates that we’re a part of) provided substantial payoffs for those who joined groups to work together. Whether our ancestors were acting as predators hoping to kill an animal or banding together to avoid becoming prey, the odds of survival increased within groups.

This has given rise to a framework known as Evolutionary Game Theory, which is explained at length in this rather technical paper. It presents equations like this in order to explain why we, and other species, sort ourselves into groups.

But across a variety of disciplines, from evolutionary biology to social psychology, most researchers agree that we aren’t suited to survive as individuals. As one research duo including the eminent psychologist Marilynn Brewer put it rather bluntly: “Even a cursory review of the physical endowments of our species—weak, hairless, and extended infancy—makes it clear that we are not suited for survival as lone individuals, or even as small family units.” Harsh, but true.

That vulnerability, according to these theories, has led to an instinctive desire to form groups. But in yet another instance of outdated evolutionary mismatch in the modern world, those groups no longer help us survive certain death at the fangs of a Saber-toothed predator. Nonetheless, we cling to them, even for no very good reason, on the basis of a coin flip, or, perhaps, a red hat.

Unfortunately for all of us, that tendency is getting worse, as more and more of us are swapping the groups we should identify with (our karass) for the empty ones that trick us into believing they are meaningful (our granfalloons).

The toxic world of hostile granfalloon politics

According to the framework of Evolutionary Game Theory, “being part of a group is more advantageous in a hostile environment than in a relaxed one,” which makes intuitive sense. The payoffs for group formation soar when the alternative is being eaten alive, but being part of a group doesn’t matter quite so much if you live in a safe environment with plentiful food and natural shelter.

This is likely part of the reason why political leaders stoke fear and a sense of civilizational collapse when they discuss the rival granfalloon that’s coming to destroy your life. The feeling of threat intensifies our evolutionary instincts, entrenching toxic in-group/out-group dynamics. When that happens, we willingly abandon humanity’s secret weapon: our intellectual curiosity.

I, too, am occasionally guilty of this in my worst moments. Rather than trying to learn how the world works, we instead insist that we already understand it and wonder why the fools in the other granfalloon don’t get it. Sometimes, they are fools—and sometimes political groupings (like neo-Nazis who would cheer the death of Tajfel’s Jewish family) can’t be reasoned with, they can only be defeated.

But we fall into a dangerous trap when we mistake a granfalloon for a karass, imagining that our political party is a meaningful identity rather than a tool to achieve a shared goal.

In this regard, modern technology is a double-edged sword. It allows granfalloons to organize much more effectively, across vast stretches of territory that were previously unbridgeable for group formation (think QAnon). But for the more discerning individual, the internet is also a magical engine for karass discovery, allowing us to connect with people who are truly like us, no matter where they live on Earth.

Unfortunately, in modern politics, it’s mostly the granfalloons that are winning.

I’ll leave you with this tantalizing thought: if you’re really lucky, you might discover that you’re part of a special kind of karass. Vonnegut highlights this in discussing a married couple who, as so many of us hope, found precisely the right person for a shared life together.

“They were lovebirds,” Vonnegut wrote. “They entertained each other endlessly with little gifts: sights worth seeing out the plane window, amusing or instructive bits from things they read, random recollections of times gone by. They were, I think, a flawless example of what Bokonon calls a duprass, which is a karass composed of only two persons.”

May you jettison your granfalloons, find your karass, and, if fortune smiles upon you, discover that you are one of the lucky ones: already living within your duprass.

Thank you for reading The Garden of Forking Paths. If you found this interesting or learned something new, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to support my writing. My work is exclusively reader-supported. And you can Ask Me Anything!

Marvelous! I love Vonnegut and you explained his concepts beautifully to describe our existence in roday’s world! Thank you for the insights and encouragement. I feel fortified for the day!

What a wonderful framework for looking at our tribalism. Though political granfalloonism has always been there to some extent, the breadth of the expressed HATRED connected with it is new since that ride down the elevator. Of course, it did begin to build steam when America dared to elect one of those "other people" as President.

I disliked George W and George Sr. but I didn't hate them, and I'm pretty sure that this was true of many on both sides when looking at someone of the other party. I hated some of their POLICIES, particularly the Gulf, Iraq and Afghanistan wars, but not the men themselves. I hated LGJ's policies on Vietnam, too--but supported him on Civil Rights.

Most of us of a certain age remember when disputes between the two parties were based on policies, and each side could give reasons why their policies were "better." Our families might be a mix of Dems and GOPs but they could discuss politics without even raised voices.

After the Descent On The Elevator, I really started wondering why tribalism was rising so. My initial theory was about something I think of as Remote Fandom. (I'm not a sports fan at all, diving for cover if sports news comes on). Sure, I supported my high school teams and my local university team, and the team of the away college I attended--they all involved people I knew directly and indirectly and I had a lot in common with the other fans for a lot of other reasons.

But when TV sports became a big deal, the broadcasters faced a problem: how do you attract a really big audience of people whose teams don't happen to be involved in the playoffs or Rose Bowls or Superbowls? Sure, some sports fans simply like the championship aspects, but for many, interest waned if your local team wasn't playing.

The answer seems to be a flogging of team loyalties to teams based far from anyone you knew. As I don't like sports, I'm not sure how it happened. But happen it did. And the result was commercially-driven Granfalloonery. Americans developed the HABIT of being in a Granfalloon. And those with an economic interest pushed this habit as if it were an opioid.

This certainly isn't the Total Answer. But I think it is part of it.