The Republican Trifecta of Extremism

America's Republican Party is drowning in a cesspool of conspiracy theories and deranged, ratcheting extremism. Why did that happen—and how can it be reversed?

Thank you for reading The Garden of Forking Paths. This is a free article. If you enjoy it and want to support my work, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription. You’ll get access to twice as many articles and it costs roughly the same as one coffee per month.

Why has America lost its mind?

In Britain, where I live, I regularly speak about US politics—in lectures, on TV and on the radio, or with people I know. And this is the most common question I get asked:

“Why have crackpot extremists taken over the Republican party?”

There’s a simple, satisfying answer: Donald Trump. And that’s certainly part of the explanation. He has singlehandedly warped his party into a dangerous authoritarian cult of personality.

But viewing Trump as the sole cause of GOP extremism is a serious error. If that were the case, the Republican Party would snap back to its more “normal” incarnation once Trump exits active politics. In that magical fantasy, Trump would leave and then…poof! The spell would break and the Paul Gosars in Congress would morph into Mitt Romneys.

Sadly, the chances of that happening are about as high as GQ magazine deciding to launch a Steve Bannon-inspired fashion guide.

To fix American democracy, we need to understand it properly. And here’s the bad news: the real problem is structural. Donald Trump just found the cracks—and broke them wide open.

Even before Trump, the United States was ripe for widespread democratic reforms. Now, it’s an emergency. But if you want to understand why we seem to be stuck with an accelerating conveyor belt of crackpots, steadily delivering crazier and crazier candidates to the halls of Congress, then there are three structural factors worth highlighting—and fixing.

I call them the “Trifecta of Extremism.”

Alone, each of them damages rational, compromise-driven policymaking. Together, they are destroying the Republican party, and by extension, American democracy, giving enormous power to deranged people who shouldn’t be trusted to operate a lawnmower without careful supervision, let alone running the most powerful country in human history.

1. Gerrymandering and elections without competition

Democracy, at a foundational level, requires competition. If people can freely vote, but the election outcomes are known before election day, then that’s not great for democracy. (The dictator of Azerbaijan once proved this point when he accidentally released fake election results the day before voting took place). And yet, to an alarming extent, the United States features a democratic system that is largely defined by uncompetitive elections.

At first, that seems like a ridiculous statement. After all, the last several presidential elections were squeakers that went down to the wire. Several high-profile federal races have been decided by recounts. But when you zoom out and look at objective data, it becomes clear that nail biters are the outliers.

The average American election is a landslide—and that’s by design.

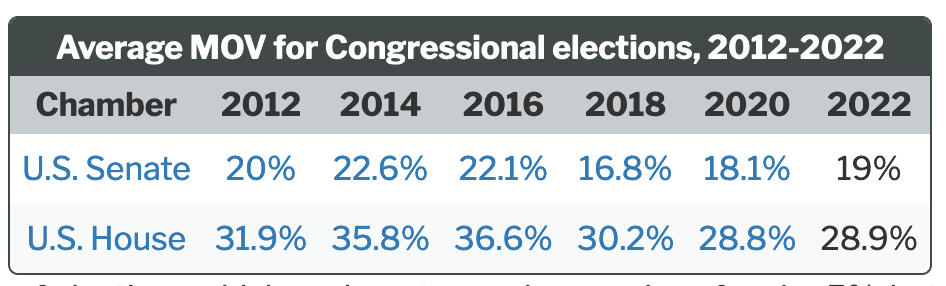

Here are the average margins of victory in recent Congressional elections (via Ballotpedia).

You’re reading that correctly: the average margin of victory in the 435 elections used to determine the House of Representatives in 2022 was 28.9 percent. In 2016, it was 36.6 percent. That means that the average House race in 2016 was a 68 percent to 32 percent blowout. The 2022 midterms were a bit more competitive, but the average race was still a 64 percent to 36 percent landslide. In 2022, only 40 House races—out of 435—were decided by a margin of five percent or less. That’s just 9 percent of the total that were genuinely close.

The overwhelming majority of Congressional races are elections without competition.

There are two main reasons for those landslides. The first is less insidious. It’s called demographic sorting. Most humans prefer to live near people who are like them. Most progressives in Minneapolis would be as horrified of the prospect of living in rural Alabama as a rural Montanan would be of living in the heart of San Francisco.

As a result, geography matters enormously in US politics, producing a feedback loop. People who grow up in cities are more likely to become Democrats, but Democrats are also more likely to be attracted to an urban lifestyle filled with like-minded people. These days, rural areas are mostly Republican; cities are mostly Democratic; and presidential elections are decided in the suburbs, where it gets more Republican the further you drive from the skyscrapers downtown.

Even if you were trying to draw a completely unbiased House district, you’d have to contend with demographic sorting. If you drew a rural district in the shape of a square, it would be overwhelmingly Republican; if you drew an urban district in the shape of a square, it would be overwhelmingly Democratic. Lack of competition is therefore partially derived from how we vote with our feet and the communities we choose to live in.

But the lack of competition has been made much, much worse by gerrymandering.

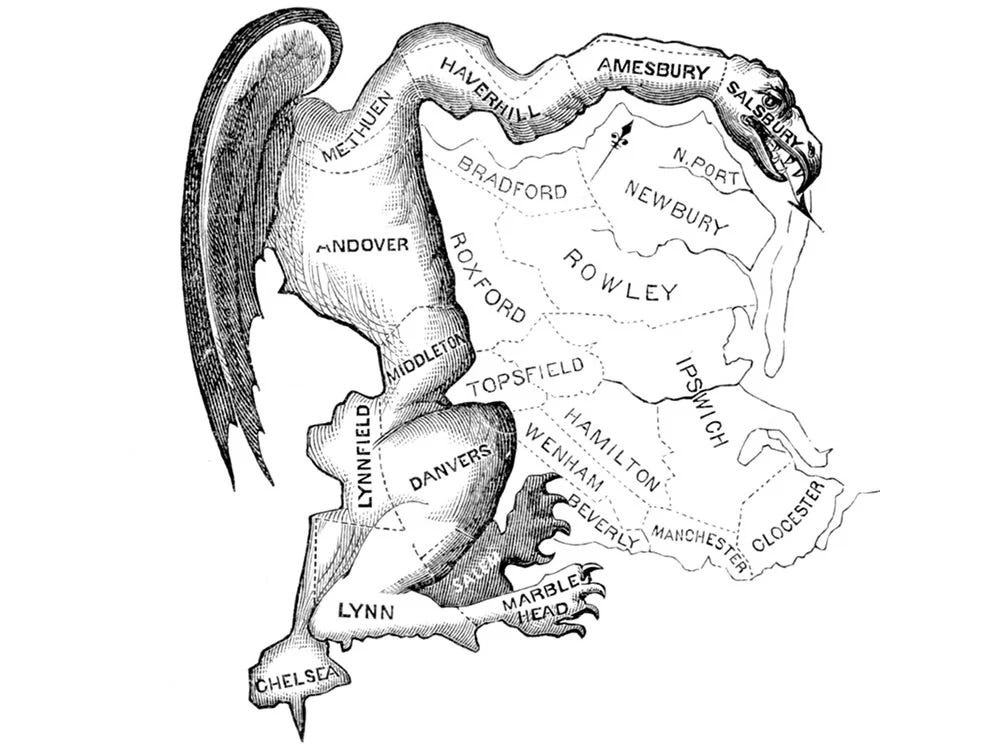

Gerrymandering is a form of election rigging in which electoral districts are drawn such that politicians choose their voters, rather than voters choosing their politicians. The term is derived from a political cartoon mocking an early 19th century Massachusetts Governor named Elbridge Gerry, who signed into law an electoral map with a notorious district that looked a bit like salamander, creating the portmanteau of Gerry and (sala)mander. Here’s the political cartoon:

Gerrymandering severely distorts democracy in a variety of ways, but one of the most harmful is that it tends to create safe seats rather than competitive ones. In the process, the uncompetitive elections that were already inevitable due to demographic sorting get made much worse. But like all forms of election rigging, the distortions to democracy don’t end after the ballots are counted. Instead, the way that elections are manipulated bleeds into the incentives that politicians face, further warping the behavior of those who win safe seats in a system designed to ensure they can’t lose.

And that’s where we get to the second part of our Trifecta of Extremism.

2. Low-turnout primaries, or why pragmatic compromise is the GOP kiss of death

Imagine you’re a Republican member of Congress who represents a reasonably average uncompetitive district in the House of Representatives. For the sake of example, let’s imagine it’s Florida’s First Congressional District, where the Republican Representative won 68 percent of the vote, and his Democratic opponent won 32 percent of the vote — right near the national average for competition.

(Unfortunately, in this scenario, you happen to be an extremist vampiric weirdo drowning in hair gel named Matt Gaetz. My apologies. But let’s proceed nonetheless, if only for the sake of example).

Now, you’re trying to decide how to behave in Congress, and this much is clear: if you play the role of loyal partisan hack, you will likely win re-election in 2024 with around 65 to 70 percent of the vote. Your risk of losing a general election to a Democratic opponent is tiny. So, where does the threat to your political survival come from?

The answer is the second factor in the Trifecta of Extremism: a low-turnout primary.

Turnout for statewide primary elections tends to hover between 20 and 30 percent in most elections, with midterm years on the lower end, and presidential election years on the higher end. That means that you don’t need that many votes to become your party’s nominee. Gaetz, for example, sailed to victory in the 2022 primary with just 57,000 votes, a tiny sliver of what he got in the general election.

Here’s a chart showing national turnout between primaries and the general election.

Low-turnout primaries provide disproportionate power to extremists within the partisan political base, because the diehards are more likely to show up than occasional voters who tend to be more moderate.

This creates the following dynamic for most Republican members of Congress in uncompetitive districts:

You cannot lose the general election to a Democrat because your district is uncompetitive.

You will lose to a primary challenger further to the right if you compromise with Democrats; if you are seen as insufficiently loyal to the GOP; or, God forbid, if you whisper a criticism of your almighty lord and savior, Donald J. Trump.

Many GOP moderates in the Trump era have found this out the hard way, either because they were defeated in primaries, or because they saw the writing on the wall and retired (anyone remember Jeff Flake?).

Of course, these structural factors existed earlier, and were ripe for exploitation. Donald Trump simply exploited them, weaponizing primaries against anyone who dared challenge him, sometimes unleashing primary challenges in tweets denouncing someone as insufficiently loyal, a “RINO” who needed to be taken out.

In that structural context, the rational way to stay in power is to appease the Trump-loving diehards in your political base. How do you do that? The answer lies with ratcheting extremism. And since 2016, that has meant out-Trumping Donald Trump.

After the 2020 election, the litmus test for GOP primaries became particularly toxic: those who lied about the 2020 election and claimed it was rigged would spare themselves a primary challenger, while those who accepted the legitimate results would invite a more extreme Republican opponent to challenge them.

What type of person succeeds in such a warped system that rewards extremism? Crackpots like Marjorie Taylor Greene, Matt Gaetz, and Paul Gosar.

Greene won the 2022 general election with 66 percent of the vote; Gaetz won his with 68 percent of the vote; and Gosar won his general election with 97 percent in his district. Due to gerrymandering and demographic sorting, none of them had anything to fear from the general election against a Democrat, but each could easily be taken out by the real election in their district, which was a low-turnout primary.

The combination of uncompetitive districts with low-turnout primaries punishes pragmatic compromisers and rewards partisan extremists.

But there’s still a puzzle: how to explain someone like Lauren Boebert? After all, she didn’t win her 2022 race in a landslide, but instead in an unexpectedly close contest that nearly saw her chucked out of Congress. Of course, some of that was her own miscalculation and some was due to polling error. But to fully explain her, we need to turn to the third and final component of the Trifecta of Extremism.

3. The rise of the political influencer in fragmented media

Lauren Boebert is a far-right QAnon sympathizer who opened a restaurant that lost hundreds of thousands of dollars a year. She would, as I’ve written previously, marry a gun if Colorado law allowed it.

But there is something remarkable about Boebert. Like Marjorie Taylor Greene, she’s a second term junior member of Congress who has already become a household name in the United States.

She’s famous for precisely one reason: because she’s an extremist.

In the past, political parties had more control over who would be the face of the party in national media. Senior party officials, including politicians who had served for decades, would decide who to trot out for a primetime interview on one of the big three TV networks. Put your time in, keep your head down, and you might get your big break.

Today, the media and social media landscape have shifted politics dramatically, allowing firebrands to bypass party controls and speak directly to fellow extremists, becoming both famous and rich in the process. That’s partly due to platforms like Twitter and Facebook, which gave politicians unprecedented direct lines of communication to national audiences, and partly due to a splintering news environment in which ratings follow extremism.

Crackpots who rile up the base also attract viewers in a hyper-partisan media landscape. That wasn’t true four decades ago, when politicians were competing for a national audience on, say, CBS.

Boebert, for her part, has 2.2 million followers on Twitter. That’s 200,000 more followers than Mitt Romney. She’s been in the House for just over two years. He was the Republican presidential nominee just a decade ago. Her national following is lucrative; she will become obscenely rich off her extremism.

She’s part of a new generation of political influencers—politicians who seek only attention, not to govern or serve the public. Their time is devoted to planning political stunts, chasing the media spotlight, or fueling outrage on social media that draws more eyeballs and clicks, a narcissistic feeding frenzy that can never be satiated.

The payoff is much quicker. In the old system, Boebert might have waited decades before breaking out nationally. In the new system, she became a star overnight.

Unfortunately, political influencers do influence public opinion. Marjorie Taylor Greene, for example, has become a dangerously normal feature of modern Republican politics. And she’s more representative of the Trump 2024 primary voter than, say, Mitch McConnell or Mitt Romney.

In short, we’ve designed a political system in which members of Congress become influential, famous, and rich if they’re extremists. At the same time, moderate pragmatists who serve their constituents face losing their jobs and remain political nobodies, obscure, forgotten, never appearing on Fox News. Like it or not, this is the system we’ve designed. And it’s beyond broken.

This, therefore, is what I call the Trifecta of Extremism:

Uncompetitive elections caused by gerrymandering and demographic sorting

Low-turnout primaries that empower extremists and diehards while systematically punishing compromise

The rise of political influencers who get rich and famous because they’re extremists

Each of these pillars of the Trifecta of Extremism has the power to erode democracy. With all three together, they could destroy it.

How to restore sanity to the GOP

There is a laundry list of reforms required to repair American democracy, but there are a few that I’ll highlight to close this edition, because they could do something positive to reverse the trends I highlighted above.

First, we need to draw competitive districts. This might require some deliberate gerrymandering—but to maximize competition, rather than safe seats. For example, districting commissions could draw districts to try to make as many close races as possible, which would force the majority of politicians to become more moderate, even to make electoral appeals to voters in the other party. But as long as most federal elections are landslides, the extremism will get worse.

Second, we need primary reform. This will require experimentation to figure out what works best to undercut extremism. Some states, such as Alaska, have introduced nonpartisan primaries, in which the top two vote getters from any political party make it onto the general election ballot. That system rewards moderates rather than extremists.

We may also need to consider more use of ranked choice voting, or in creative efforts to expand turnout to dilute the extremist diehards in the political base. But as long as a tiny, extremist slice of the electorate determines who ends up on the general election ballot in November, the conveyer belt of extremism will keep humming along, faster and faster each election cycle.

The third problem—of political influencers and splintering media outlets—will be harder to fix, but its toxicity would be reduced if the first two problems were solved. If you make a system in which extremists have a harder time winning elections than moderates, then political influencers will still have a significant reach, but hopefully that reach won’t include formal political power from within the halls of Congress.

Donald Trump did more to unleash the forces of extremism on the United States than any other individual in modern American politics. But he was largely exploiting structural problems rather than creating them. And until we come to terms with the sobering fact that GOP extremists will continue their dominance of the party well after Donald Trump is long gone, we won’t tackle the root cause of the problem, which is the Trifecta of Extremism.

Thank you for taking the time to read this edition of The Garden of Forking Paths. If you’ve enjoyed it, please add your name to the e-mail list (for free), or if you’d like to support my work so I can write more articles like this, sign up for a paid subscription for the low, low cost of roughly one coffee per month to caffeinate your brain.

Excellent, Brian. I just want people to know that some Americans can and do change their minds. I’m one. I lived in Newt Gingrich’s district in my 30s, and idolized him for a long time. I listened to Limbaugh every day. I voted R no matter what. I thought FoxNews was the greatest thing since sliced bread. Gradually my eyes were opened through the GWB years, watching the viciousness & vitriol re: immigrants. One day I literally got sick of my own bullshit, parroted unthinkingly for so long. I realized it was an act, a stance for the purpose of conquest and nothing more. I reconnected with my church and its actual teachings, not the Falwell et. al psycho version. I began to read widely and unplugged the g-d tee vee. Ahhh, silence. It’s golden.

Luckily, my husband has been in lock step with me through this journey. Because guess what? He’s the single person I have left as a likeminded companion. To a man and woman, I’ve lost (shed) 99% of fam & old friends. The pandemic sealed the deal, when the nutty & unhinged political toxins turned humans I knew into lethal weapons. Oh well. You can’t pick the times you’re born in, just your own response to them.

We found you several years ago - pre-pandemic. And we have learned so much from you and value your perspective beyond measure. You’ve given me personally many great & lasting gifts. Thank you.

My question is "- why haven't we seen the same thing happen to the Democrats? Sure there might be some Congressmen on what people might consider the far left, eg asking to defund the police, but by and large you don't have the same degree of extremism on the Democrats side, at least for now.