The Red Queen Fallacy

Humans weren't made to tick off checklists and clear inboxes. We've lost sight of who we are, amid the mindless excesses of hustle culture and a drive-thru existence. Here's the case for slowing down.

Thank you for reading The Garden of Forking Paths. If you want to support my work, consider upgrading to a paid subscription (it’s just US $4/month with an annual subscription). You can also check out my book, FLUKE. And thank you for sharing with me your most precious commodity: time.

I: The Red Queen Fallacy

There is an unsettling paradox that is central to modern life.

We are, in many ways, the most liberated people to ever live, free from endless toil in unforgiving fields, able to feed, shelter, and clothe ourselves with ease. Despite crushing inequality, we live in the richest period in human history. We have more control over our lives than any of our ancestors.

And yet, one of the most common, overwhelming sensations of modern life is frantic stress as we race—but often fail—to keep up. For too many, life feels like a treadmill without an off switch.

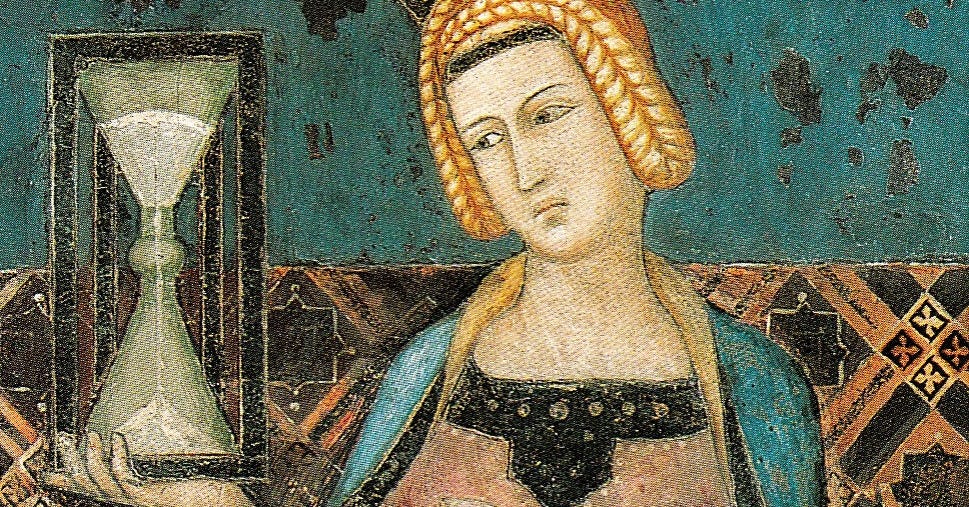

In Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass, Alice finds herself in a strange world, where everything seems to be backwards, a lesson she learns as she begins running with a mysterious character known as The Red Queen.

“The Queen kept crying “Faster! Faster!” but Alice felt she could not go faster.” No matter how fast Alice ran, she never got to where she was going. “However fast they went, they never seemed to pass anything.” Finally, the Queen propped Alice “up against a tree, and said kindly, “You may rest a little now.”

As Alice catches her breath, the Queen explains that life works a little differently in her strange country:

“Now, here, you see, it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place.”

The parable of the Red Queen1 has become a warning for modern life, where many of us inhabit that same type of strange country. We too often experience our existence as a frantic race to keep up, a frenzy of typing fingers and stressful calendars, racing toward an unknown destination but never quite arriving.

This has given rise to a central delusion of 21st century living, what I call The Red Queen Fallacy. If you’re not hustling, you’re falling behind. If you’re not working toward a goal, you’re wasting time. And if you’re not racing to keep up, you’ll never get where you’re supposed to be going.

None of that is true.

But the Red Queen Fallacy helps explain why, as the South Korean philosopher Byung-Chul Han puts it, “Haste, franticness, restlessness, nervousness and a diffuse sense of anxiety determine today’s life.” We schedule a dinner with a long-lost friend, only to find out that the next available window is in six weeks. Too often, in the meantime, we’re unthinkingly living a drive-thru existence. Efficiency is paramount because everything feels like a race that never ends.

Racing to keep up, we tend to find it exotic and eccentric when people linger without a purpose, when one wanders aimlessly, or when we see a stranger sitting and thinking in public without a smartphone as a distraction. The solo diner without a book or phone is seen as a weirdo; the person who wanders alone for hours in nature deemed a loner.

Constant hyper-activity hasn’t just defeated patient stillness and slow reflection—what Hannah Arendt called the vita contemplativa. Instead, the modern rat race has massacred it so much that many of us can’t even handle being forced to be alone, with nothing but our minds as company.

In one study, scientists placed people alone in a room with nothing but a button that would deliver a painful electric shock. Given no direction, the subjects were free to sit quietly with their thoughts. Instead, 67 percent of men and 25 percent of women shocked themselves rather than face the discomfort of lingering without something to do.

The world of the Red Queen is not a strange foreign country in a childlike fantasy. It is modernity. And for too many of us, it’s unfulfilling. Or, as Charles Foster put it in Being a Human: “We are materially richer than ever before…And yet we are ontologically queasy.”

The trouble with all that hyper-activity, that endless race, is that on every metric that really matters, we truly are stuck in place. In psychology, this dynamic is known as the Hedonic Treadmill, in which human beings tend to have an equilibrium of happiness that they return to, even after they successfully achieve a goal or face a setback of failure.

Always racing forward, we go nowhere. Worse, unlike Alice, we rarely pause to catch our breath.

II: The Toxic Myth of Hustle Culture and the Checklist Paradox

As the essayist Maria Popova reminds us: “to live wonder-smitten with reality is the gladdest way to live.” We are born living that way. It is often stamped out of us.

Humans are ever-striving beings. But in an ideal world, embedded in that impulse for striving must be a sense of passion, not for the material gains or fleeting status accrued from a given activity, but from the joy of it for its own worth.

This is a lesson not just forgotten, but actively attacked, by the destructive ethos of hustle culture, an attitude which dominates the high-flying echelons of modern life—and seduces those who wish to inhabit that seemingly hallowed ground.

This is the realm of thinking that, when we follow it, willingly places ourselves on a human hamster wheel, scurrying within the tyranny of tasks. We may accrue wealth and status through hustling, but the scripture of hustle culture espoused on YouTube channels and podcasts tells you that it will never be enough. Every successful hustle gives way to another one. Happiness lies in life hacks. Everything that matters can be measured—and if you don’t have a metric to showcase what you’ve achieved, why bother? If you didn’t quantify it, do you even live, bro?

These toxic myths have become pervasive partly because of the warped culture of Western modernity—in which hustling is seen as virtuous and admirable (how many hours did you work this week?)—and partly because broken models of under-regulated capitalism that produce severe inequality have left millions pursuing a life of empty hustles simply because they don’t know how else to make ends meet or how to create a safety net for themselves and their families.

Regardless of its origins, hustle culture is the pinnacle of what I call a checklist existence, the ultimate form of a world in which every box we tick gets replaced by yet another one, the same way that e-mail inboxes are the ever-regenerating many-headed hydras that plague our daily lives. We slay them endlessly, hoping that each slash of the delete key or reply button will get us closer to that mythic allure of “inbox zero,” a profoundly dystopian goal.

In that never-ending battle, which we always lose, the checklist itself becomes the achievement, an utterly bizarre, tragicomic approach to living—and yet one that, like most of us, I struggle to resist. We are, too often, chained to our checklists, inmates held inside our own inboxes.

There is a problem with this lifestyle, which seeps through every aspect of modern society. I call it the checklist paradox. It works like this:

Doing more often means savoring life less.

I don’t mean that in the sense of raw human longevity, but rather in the lost, vibrant moments that make long lives most worthwhile.

These are the moments that, in the words of the German sociologist Hartmut Rosa, are moments of “resonance,” in which to-do lists are obliterated from our minds and we simply enjoy the ecstasy of a snapshot in our lives, whether it’s a euphoric interaction with other people, a sense of awe in the face of natural beauty, or the joy of acquiring fresh, outlook-altering knowledge.

We all know, deep down, that these are the moments worth having—the memories that will last and still make us smile when we look back at them while facing death—and yet the dominant mentality in modern life seems to be its opposite. Rosa describes that prevailing worldview—the mantra many of us follow that strangles those moments—like this:

“Always act in such a way that your share of the world is increased.”

Trapped within that worldview and beholden to a beast that can never be satiated—no matter how much of the world we feel we “own”—we can lose sight of the meaning of our lives. Often, that’s because we end up mired in what the late anthropologist David Graeber called “Bullshit Jobs.” Some unfortunate jobs are, indeed, entirely bullshit, while others just have elements of bullshit laced within them. (Nobody is fully exempt from pointless tasks).

Bertrand Russell, writing in 1932, summarized the world of work like this:

“What is work? Work is of two kinds: first, altering the position of matter at or near the earth’s surface relatively to other such matter; second, telling other people to do so. The first kind is unpleasant and ill paid; the second is pleasant and highly paid…[But] the fact is that moving matter about, while a certain amount of it is necessary to our existence, is emphatically not one of the ends of human life.”

Don’t get me wrong: I love my work. I hope that you do too, or that you’re able to find meaning in it even if you are—or were—stuck in a job that has an unfortunately lopsided ratio of drudgery to passion. Hard work with passion—either for the actual work or for the people who you share it with—is one of life’s great joys.

The trouble begins either when we make the mistake of viewing a “Bullshit Job” (and the ladder climbing within it) as the central meaning of our existence, or when the time away from the job becomes defined by the necessity of recovery and “recharging,” so that even leisure itself ends up in servitude to the work.

Human life—the most extraordinarily improbable and miraculous outgrowth of 13.8 billion years of the universe existing—should not be wasted. We were not made to clear inboxes or toil in spreadsheets. I am not sure what “the meaning of life” is—if there is one—but I am sure that most possible meanings worth pursuing will be derived from what we do with other people, not whether we hit quarterly targets or drive fancily shaped hunks of metal.

I think about it like this: if the Earth were walloped by an extinction-level asteroid tomorrow, which parts of my life would be a loss to the universe? Those are the bits I should focus on most.

Charles Foster, who tried to escape modernity and live like a prehistoric human for extended periods of time, came away from the experience concluding that “we’re wild creatures, designed for constant ecstatic contact with earth, heaven, trees and gods.” And yet, we’ve foolishly tamed ourselves—with e-mail jobs and ChatGPT task management, boasting on CVs about our prowess with Microsoft Outlook and Excel.

We have a sense of control, even domination, over the world. We have built unimaginable prosperity. But many of us still feel like we are the ones being controlled, by the straitjacket of modern life. “I’d love to do that, but I just can’t get away,” is not a mantra dripping with a sense of jubilant liberation.

Can we ever break free?

III: The Lost Art of Contemplation, or Why We Should Slow Down

Humanity is the only phenomenon in the known universe that contemplates its own existence. As far as we can tell, we’re the only consciousness that considers why it’s here. It is one of the reasons, perhaps, why Aristotle and Plato emphasized the role of contemplation in an ideal life—and why the philosopher and guru Alan Watts remarked that “through our eyes, the universe is perceiving itself.”

Of course, there are good reasons why we’re unable to slow down and contemplate the bigger picture, why we get stuck in the checklist existence rather than embracing what Arendt called the vita contemplativa—the contemplative life.

Modern society pushes us away from reflection and toward hectic lifestyles and bullshit jobs. Still, we can’t all just abandon our responsibilities and go backpacking for months in the mountains or become permanently withdrawn hermits who ponder the bewildering question of what it means to be a human. After all, who would do the spreadsheets when we’re gone?

But a warning is nonetheless worthwhile, as Byung-Chul Han cautions:

“If the human being loses all capacity for contemplation, it degenerates into an animal laborans. The life which adjusts itself to the mechanical work process knows only breaks, work-free interim periods in which the regeneration from work takes place in order to be fully available again for the process of work.”

Halfway through the pandemic, I looked back at my Google calendar from February 2020, a month before the coronavirus upended all our lives. I saw a wall of colored blocks—a checklist existence translated into scheduling commitments, including many that I agreed to attend based on some speculative concept that it would be “good for my career” in some unknown, abstract way. What I didn’t consider is whether it would be bad for me.

There are fewer colored Google blocks and fewer plans these days—and I’m happier. And while I’m still trapped in a mentality that was drilled into me for literally decades, I try (but often fail) to make more space for contemplation and pauses—and less space for scurrying, overly scheduled time, and Red Queen-style racing. There are trade-offs. There are costs. But to me, it’s worth it.

There’s also an easy shift that everyone, no matter their responsibilities or commitments, can make: to think less of the instrumental purpose of any moment—“what can I use this for?”—and focus instead on what Rosa calls the moments of “resonance.” This is a point highlighted by the exquisite writer Karen Armstrong in her book Sacred Nature, where she chastises us—I, too, plead guilty—for how we behave in the presence of that which should simply move us:

“We walk in a place of extreme beauty while talking on our mobiles or scrolling through social media: we are present, yet fundamentally absent. Instead of sitting contemplatively beside a river or gazing in awe at a mountain range, we obsessively take one photograph of the view after another.”

It’s a phenomenon captured beautifully by a photography series called Removed, by Eric Pickersgill, in which he captures moments of everyday life, but brushes out the devices we’re holding. With the devices removed, the absurdity of these scenes bludgeons us over the head.

But these aren’t merely artistic creations. This is real life, the dystopian images I see when I spot children at the bus stop before school, silently scrolling, never speaking— laughing at videos, never each other.

To me, the good life has more aimless wandering, less frantic racing, more spontaneity, less scurrying. It comes with a slower pace that allows us to catch our breath, to soak up wonderful moments, to savor what we have. It gives us the space to do one of the most important things a human can do: to notice and relish the joyful, the fulfilling, or even the merely pleasant bits of life. Or, put much better, by the great writer Kurt Vonnegut, who shared this gem of wisdom, passed down from his Uncle Alex:

One of the things [Uncle Alex] found objectionable about human beings was that they so rarely noticed it when they were happy. He himself did his best to acknowledge it when times were sweet. We could be drinking lemonade in the shade of an apple tree in the summertime, and Uncle Alex would interrupt the conversation to say, “If this isn’t nice, what is?”

So I hope that you will do the same for the rest of your lives. When things are going sweetly and peacefully, please pause a moment, and then say out loud, “If this isn’t nice, what is?”

Thank you for reading The Garden of Forking Paths. If you found this edition interesting, or you just want to be kind and support my work so I can keep doing this thing I love—writing for you lovely, intellectually curious bunch of people—then please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to support my work. And please do forward this on to someone you know who might find it interesting, uplifting, or thought-provoking. Every bit helps.

In evolutionary biology, the Red Queen hypothesis provides one possible explanation for the evolution of sexual reproduction.