The Day Four Million Children Disappeared

A peculiar episode from 1987 teaches us crucial lessons about incentives in the public sector, the overwhelming impulse for humans to be honest, and the need for smarter systems in government policy.

Thank you for reading The Garden of Forking Paths. Part of this edition is for paid subscribers only, including my 15 recommendations for what to read, watch, and listen to. If you’d like to support my work, please consider upgrading to paid. If not, no worries—and please forgive my inbox intrusion. The next fully free edition returns early next week.

In April of 1987, roughly four million American children went missing. They disappeared without a trace, never to be mentioned again. They were never found.

Where did they go?

The answer, it turns out, provides crucial insights into how government works—and doesn’t work—along with delivering lessons for how to better design systems. Plus, this story provides a nice little boost to those who believe that most people are generally good and honest, but that we should devote more resources to catching those few who aren’t.

The IRS and the Case of the Missing Children

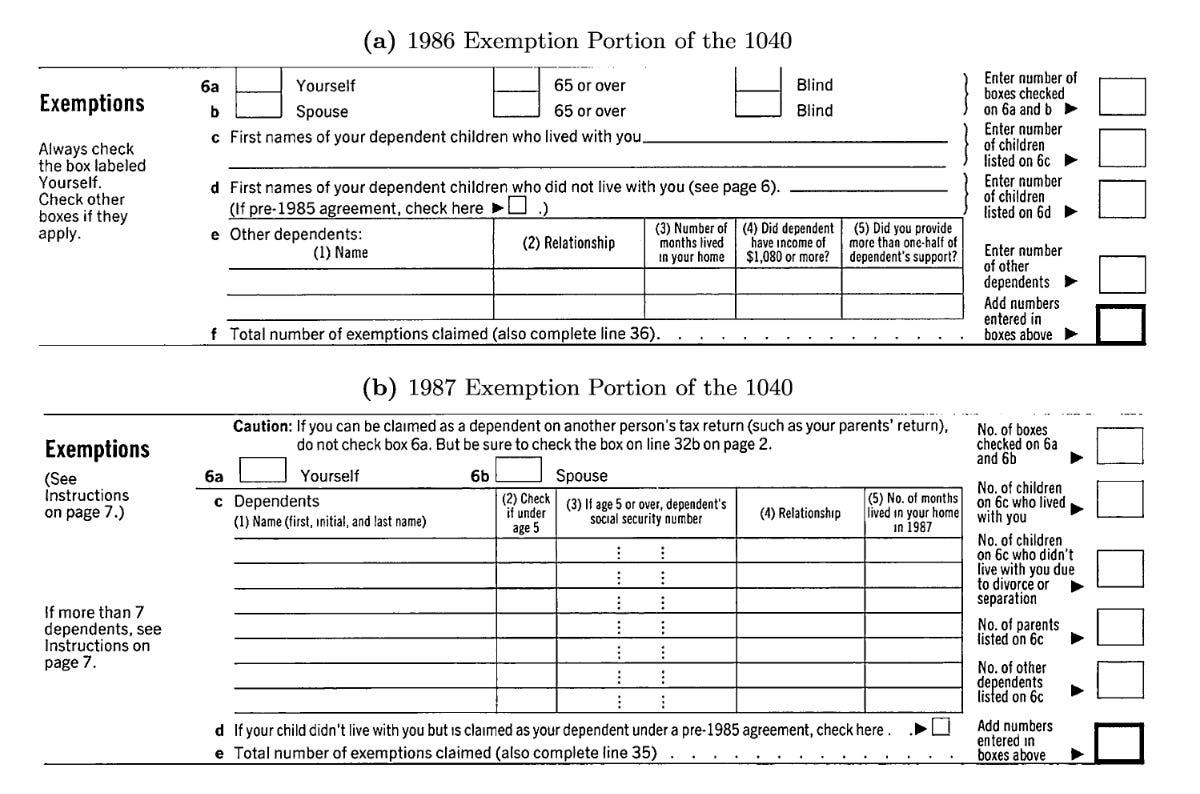

In 1986, Congress passed a tax reform bill that made a few changes to American tax forms. The new form was rolled out for the 1987 tax season. Here’s a photo that shows the two versions of the relevant area of the tax form, with 1986 on the top, 1987 on the bottom. Now, before I explain what you’re looking at, take a look and try to figure out what the one crucial change is between these forms. (Go on, give it a try before scrolling down).

The answer is part c), question 3) on the 1987 form, which, for the first time, asked taxpayers to list their dependents on the form with their Social Security Numbers. This simple change caused millions of children to suddenly disappear. (The number that is usually cited is seven million, but further analysis suggests the true figure is closer to four million, which is, I’m sure you’ll agree, still quite a few kids).

Four million kids gone. What happened?

In the mid-1980s, an Internal Revenue Service (IRS) researcher named John Szilagyi noticed something peculiar about many of the tax forms he examined. The names of the dependents—only first names were required—sometimes seemed a bit off. For example, one taxpayer claimed a dependent named “Fluffy,” which, you might be aware, isn’t a standard name for a human child.

Szilagyi wondered: how many of these “dependents” were fictional? Were people cheating on their taxes by inventing children—and sometimes pretending their pets were their kids? (OK, I treat my dog Zorro like he’s my son, so I understand the impulse, but I don’t use him for tax breaks).

Within the IRS, some were skeptical about the proposed change, and a few even pushed back hard, arguing that the proposal to collect that data was drifting dangerously toward George Orwell’s dystopia of 1984. (Imagine what they’d think of, say, Meta, today).

But eventually Szilagyi—a one man advocate for this subtle policy change—prevailed. The form changed. And sure enough, millions of dependents claimed in 1986 weren’t claimed in 1987. They were never claimed again.

Guess how much money it saved the US government? At least $3 billion a year.

What’s striking, though, is that the changed form didn’t come with an overhaul of auditing procedures. Even after the lines for Social Security Numbers were added to the form, it was still pretty easy to get away with tax fraud by falsely claiming invented children as dependents. That’s because the IRS had limiting computing power, so they only were able to match and verify Social Security Numbers for a measly three percent of all claimed dependents. If you were inventing a child in 1987 for a tax break, you still had a 97 percent chance of getting away with it, even if you’d just made up a fake Social Security Number.

This story isn’t very well known, but when it is told, it’s usually associated with some level of insight into behavioral economics, a “nudge” that worked, a slight tweak that had profound impact. I think that’s the wrong lesson here. Instead, there are much more potent conclusions to be drawn from this case of the disappearing children.