The Age of the Surefire Mediocre

Why have so many aspects of our lives converged toward boring sludge?

Thank you for reading The Garden of Forking Paths. This edition is for everyone, but if you value my work and would like to support my writing—while unlocking the full archive of 200+ essays—please consider upgrading for just $4/month. Alternatively, you can support my writing by buying my book: FLUKE.

There are two facts that, if you knew them about me, would cause you to badly misjudge how old I am. The first is that I love Hercule Poirot mysteries. The second is that I have a curmudgeonly viewpoint about modern culture: that too many mainstream creative industries have taken a nosedive, replacing innovative genius with average sludge.

We have, in my view, entered the Age of the Surefire Mediocre, in which the corporate money behind human creativity is flowing increasingly toward guaranteed hits that are similar, boring, and average. Creative genius still abounds. But when you look at blockbuster film listings, pop hits, and bestseller charts, there are quite a few middling sequels, reboots, celebrity autobiographies, and bubble gum histories written by cable TV news hosts.

This unfortunate shift is poorly timed. In the 1990s, doomsayers warned that new technologies—robot arms and mechanized machines—would put ordinary people out of work.

These days, though, large language models and artificial intelligence threaten to disrupt, even destroy, large swaths not of menial labor, but of human creativity. Technology can either make us more human or less human. Machines that free us from menial tasks to do things we love make us more human. But if we’re stripped of the essence of human creativity, that makes us less human—and it should be resisted. The threat is so acute that the Writers Guild of America has proposed new rules that would allow AI to be used to write film and television scripts.

The depressing question is this: would we even notice if AI sludge replaced some of the writers for blockbusters? Possibly not, given what’s being churned out by Hollywood and slurped up by audiences. Take a look at the Top 10 highest grossing films of the last decade or so:

Avengers: Endgame (superhero sequel)

Avatar: The Way of Water (sequel)

Avengers: Infinity War (superhero sequel)

Star Wars: The Force Awakens (reboot / sequel)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (superhero sequel)

Jurassic World (reboot / sequel)

The Lion King (reboot)

The Avengers (superhero)

Fast & Furious 7 (sequel)

Top Gun: Maverick (reboot)

The only original film on this list is the first Avengers movie, and even that is just a cinematic adaptation of a comic book universe that was already largely conjured up by others in decades past. As the writer Kurt Andersen observed: “Our culture's primary M.O. now consists of promiscuously and sometimes compulsively reviving and rejiggering old forms.”

It’s gotten so ridiculous that new Lord of the Rings films are currently being produced, shortly after Amazon just poured $715 million into a decidedly mediocre Lord of the Rings TV show. HBO is creating a Harry Potter TV series. The top grossing films of 2025 so far are a movie about a videogame; a Captain America reboot; and a remake of Snow White.

It’s not just films, either. As the writer Alex Murrell has elegantly highlighted in this excellent essay, in design, there’s a “creative convergence” toward the similar, the bland, and the average. Take a look, for example, at how Murrell has highlighted the standard American apartment building — the “five over one” architectural style, which, if you’re American, you surely recognize in your local community.

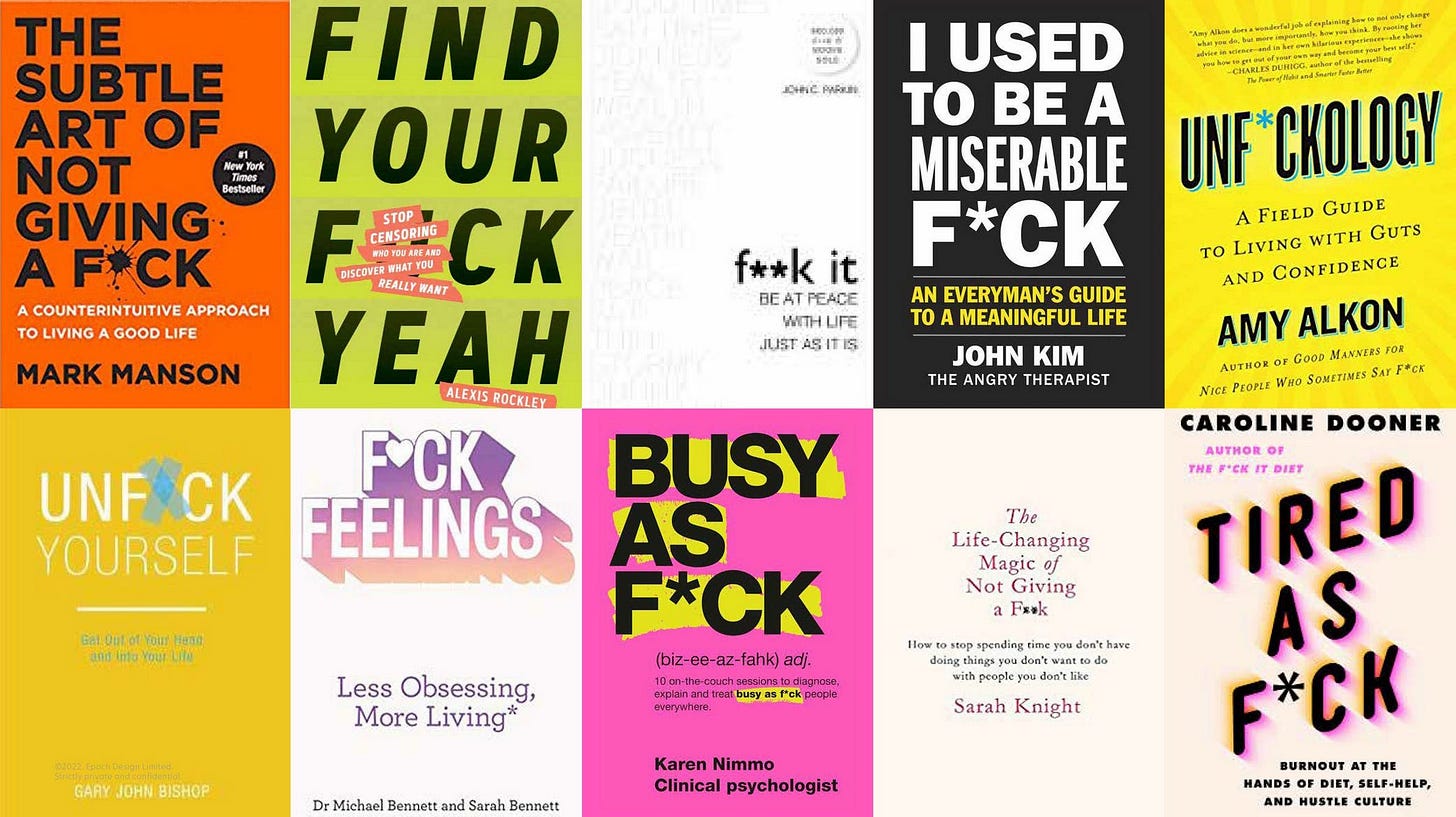

In book publishing, Murrell points to a similar creative convergence in the cover art for what he calls the “sweary self-help book.” Take a look for yourself:

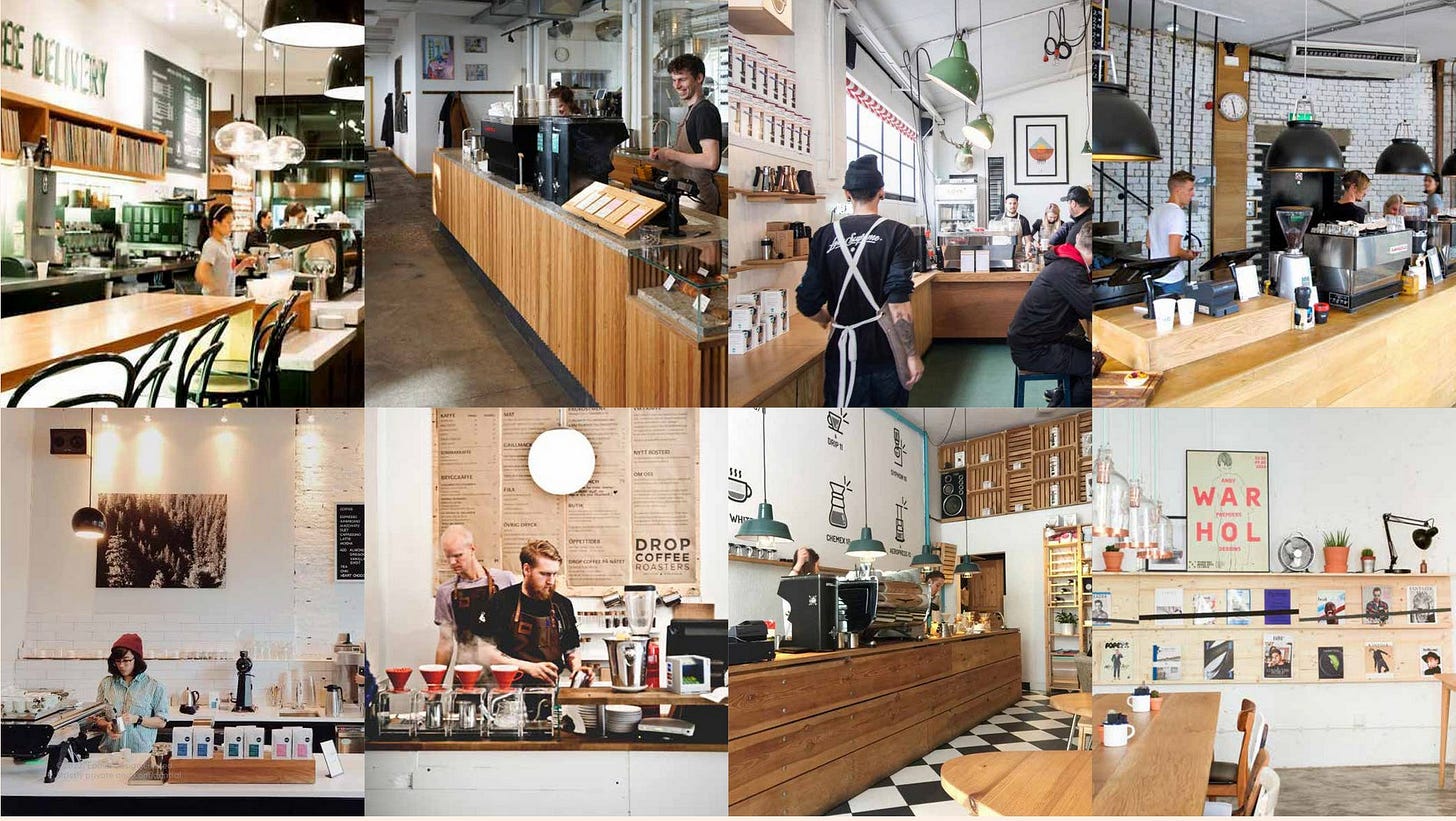

Finally, Murrell points to the design aesthetic within our cafe culture. There was, at some point, an innovator who realized that there was something edgy, clean, and modern about industrial chic. Suddenly, it took over. It became the standard, ending its claim to being edgy, and instead just becoming boring and average, like the Goth kid in 1990s high schools who hoped to show that they were different. They did so by buying all their clothes, like all the other countercultural Goths, from a corporate chain called Hot Topic. (Nothing shows countercultural authenticity and fighting The Man quite like buying from a suburban shopping mall retail chain acquired for $600 million by a private equity firm called Sycamore Partners).

Take a look at this random assortment of cafes, compiled by Alex Murrell. It doesn’t matter where you live in the Western world; odds are that they look familiar to you.

So here’s the question: why is this happening? There’s no single answer, but I’ve got a few possible solutions to the puzzle.

The Age of Analytics

We live in an era of predictive analytics, in which creative decisions are increasingly driven by computer models that aim to try to predict what will—and will not—be a hit. Now, pause and think about how that works for a second, and you’ll see that it will inevitably lead to convergence toward, you guessed it: the Surefire Mediocre.

When models are trained on past data, they are deliberately trying to replicate past successes. If your analytics model were trained to maximize profits in 2025, and it looked at the highest grossing films of the last decade, it certainly would not suggest that the best way to make money was to try something different or innovative.

After all, if Fast & Furious 7 was a major moneymaker, then the predictive analytics would insist that Fast & Furious 8 would follow suit. It has transformed the biggest pots of money for entire creative industries into a version of “If it worked last time, it’ll probably work this time, too.” It’s a safe bet, with a guaranteed payoff. And it works.

This dynamic is the same reason why those who use machine learning models for hiring have to be careful about entrenching bias. When the models are trained without care, all they do is replicate the existing demographics at the top levels of the company. If you train your hiring and promotion algorithm based on the people who are successful at the highest levels in your company now, then you’re effectively training the model based on all the sexist and racist biases of, say, the 1980s and 1990s—when the top management was originally promoted to the most senior echelons of the business.

That’s the danger of an uncritical machine learning model: when done badly, it can converge toward reinforcing the status quo, which is the opposite of human innovation produced by experimentation.

A creative convergence has also happened in some realms of publishing, in which there are now a lot of really similar books that follow the same basic structure. We can all recognize the pop non-fiction books—particularly for business—that you see at airports. There’s the minimalist cover—often white—with the catchy title/subtitle combination. Then, there’s the predictable 220 pages of text that would have been better as a twenty minute TED talk. (Heck, the book probably did start out as a TED talk).

But here’s the thing: like Fast & Furious films or Avengers sequels, those books sell. What they don’t do is transform us or shift our thinking beyond providing a few good anecdotes. They’re the intellectual equivalent of Jurassic World: entertaining, mildly interesting, good for a flight. But while Jurassic Park was at least new, interesting, and exciting, Jurassic World was just a bunch of eye candy on a screen, re-hashing a familiar formula. Dopamine, not depth.

Then there’s the recent explosion of the “History of X in some number of Y” genre of books that have recently busted bestseller charts. The History of the World in Twelve Shipwrecks. A History of Britain in Ten Enemies. A History of the Roman Empire in 21 Women. A History of the World in Six Glasses. These are standalone bite-sized chunks that often read like well-written Wikipedia entries smooshed together, not actual books with beginnings, middles, and ends, and they’re perfect for people who want to read something—but just six minutes at a time.

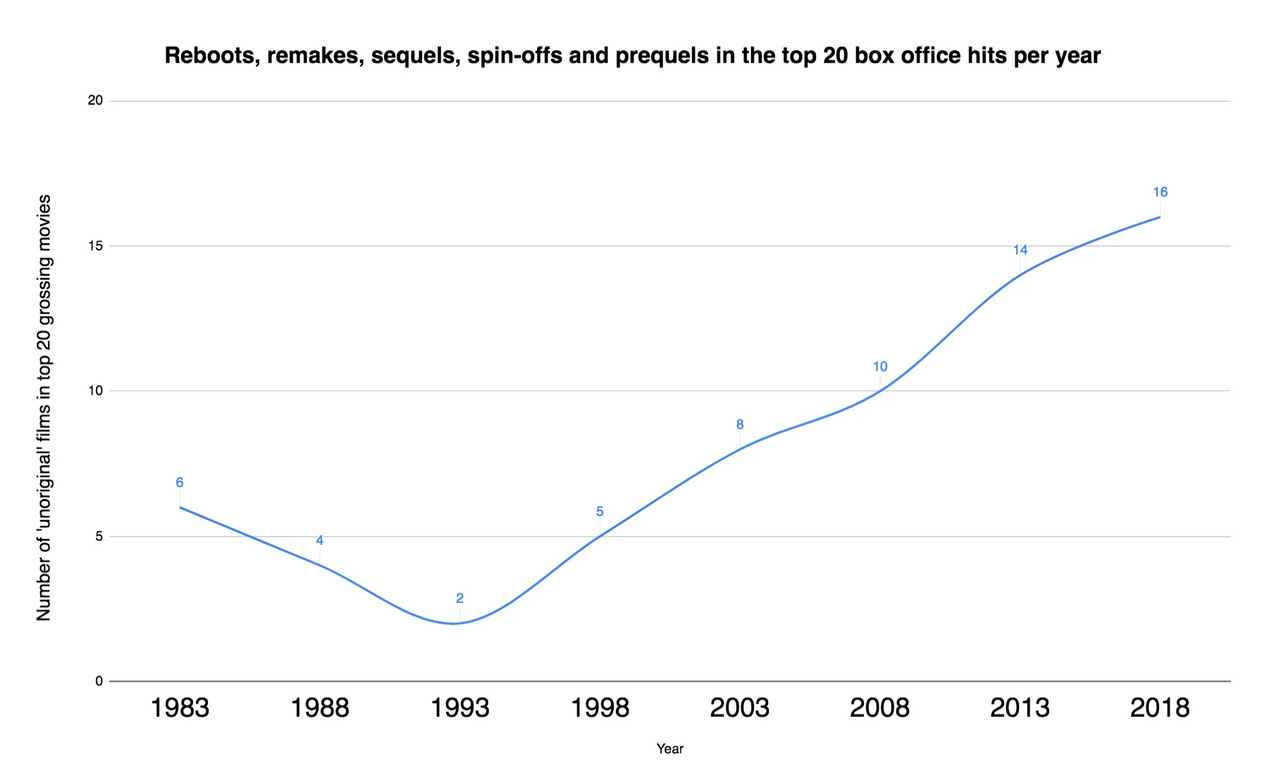

What is the end result of the Age of Analytics? A world in which films are mostly reboots, remakes, sequels, and spinoffs. This chart, from a few years ago in Radio Times, shows what proportion of top 20 grossing films from that year fit those labels. Just take a look at the top grossing films last year. It’s depressing—and it’s steadily getting worse.

Predictive analytics has led to what Derek Thompson at The Atlantic calls the “Moneyball-for-Everything” society. Moneyball refers to the use of computer-optimized strategies in baseball, in which a game that used to be the most romantic sporting past time in American culture, was turned into a Solve for X computation.

What happened? The game became slower, more boring, and began to lose fans. Now, Major League Baseball has had to institute new rules to try to bring back the excitement that exists when flawed humans, rather than ever more precise metrics, are showcased on the field. Some pursuits, like cancer treatment, should be optimized. Human creativity, by contrast, thrives on disorder, experimentation, innovation—not a script based on what sold well in the past.

But as Thompson writes, the objective, data-driven analytics revolution had profound consequences for human creativity, including in the music industry:

Before the ’90s, music labels routinely lied to Billboard about their sales figures to boost their preferred artists. In 1991, Billboard switched methodologies to use more objective data, including point-of-sale information and radio surveys that didn’t rely on input from the labels. The charts changed overnight. Rock-and-roll bands were toppled, and hip-hop and country surged. When the charts became more honest, they also became more static.

Keep in mind that this phenomenon is taking place within the context of competitive corporate business. Creativity is the pinnacle of humanity; it’s what separates us most from other species. The endless cultural engine we have firing constantly in our heads is perhaps the most astonishing outgrowth of evolutionary biology. So why are we suppressing it? The answer, as is so often the case, has to do with profits.

The Surefire Mediocre is High Profit, Low Risk

A few years ago, I went to a book launch at Bloomsbury Publishing. I shook hands with the man who bought Harry Potter after countless other publishers had rejected it. It was arguably the greatest creative business investment of all time. He reportedly paid $3,300 for the rights, for a book series that has sold 500 million copies since. It turned Bloomsbury from a boutique, independent publisher into a major titan of the book world.

And while Harry Potter is an extreme outlier, the creative industries have baked outlier successes into their business model. After all, Bloomsbury could have greenlighted a series of flops after Harry Potter and it wouldn’t matter—they’d still have turned an enormous profit. It insulated them from creative risk.

However, while it’s likely that every so often a film or TV show or band or book will break out from an otherwise unknown artist, it’s guaranteed that an Avengers film or a crappy book written by Tucker Carlson (and plugged by him on the podcasts hosted by his influential, bigoted friends) will make a ton of money. In other words, if you chase the Surefire Mediocre, there is no risk.

That’s good for business. But it’s bad for all of us, because we just keep getting a dreary cultural convergence toward the unremarkable and the passable, churned out by those who already have deep pockets and big platforms.

Globalization and the Great Standardization

I’ve been fortunate to travel, or live in, some of the most un-globalized places you can find, having spent countless months conducting research in Madagascar, or living for several months in Togo, in West Africa. But even there, I was astonished by moments of cultural convergence, such as when I sipped a coke at a roadside bar in Lomé, Togo—a place with few paved roads—and asked the owner if they’d put on the local radio station for me. They did, and soon the familiar sounds of The Pussycat Dolls filled the air.

Such experiences, in a globalized world, are inevitable. But what’s not inevitable, and is instead an unfortunate choice, is for the creative industries to put so much money behind cultural products that are one-size-fits-all sludge.

In 2020, for the first time ever, China’s film box office overtook the domestic American market, with both of them just under $2 billion in overall value. Similarly, China is also now home to the largest video game market in the world, and it dwarfs the film industry ($46 billion in video game revenues in China; $40.5 billion in the United States).

The economic incentives have therefore shifted, in which creative productions gravitate toward global, rather than localized appeal. And yet, many of the best forms of creativity have to be culturally specific if they are to feel authentic and innovative. That doesn’t mean that we can’t enjoy stuff from another culture—far from it, as the breakout independent French film Amélie proved when it came out two decades ago and took the United States by storm.

But it does mean that trying to produce a creative product that is so culturally elastic that it can appeal equally to a Chinese and American market—despite all the vast differences in those societies—will inevitably lead to a stripped-down standardization. The film Amélie charmed us because it was so French, not because it was universal.

Is it our fault?

So, how can we fix it? This is the great cultural chicken-or-egg conundrum of the modern world: is it the fault of corporate money that we’re doomed to be watching Avengers 27: Endgame Infinity Plus Plus Plus in the year 2047, or is it our fault because we keep buying tickets to bland reproductions of an endlessly repeated script?

The answer is, as you might suspect, a bit of both. Our choices are constrained, but we feed the corporate convergence with our wallets, reinforcing the machine learning algorithms by proving their predictions right. Even if we stopped—even if Western consumers began to boycott the Fast and Furious films—it wouldn’t matter so much, because billions of dollars from the global box office would still make it worth it to Hollywood.

And yet, despite my curmudgeonly critique, there is plenty of cultural innovation and an endless fount of creativity, if you know where to look. That’s the paradox of modern cultural life: we’re living in an astonishing renaissance for so much creative and artistic expression, but the most interesting and edgy content is too often that which is least visible in a corporate-dominated creative sphere.

As I was writing this, as if to prove this point, I watched a charming, but very strange film called Brian & Charles, which wasn’t quite like anything I’d seen before. It was delightful. I was utterly charmed. It won artistic awards.

And then, it grossed $860,000 at the global box office. But even though its creators may not have struck it rich, at least it didn’t warrant that depressing label that applies to so many hits in modern culture: the Surefire Mediocre.

Thank you for reading The Garden of Forking Paths. This edition was for everyone, but if you would like to support my work by upgrading to a paid subscription, $4/month gets you access to the entire collection of 200+ essays. Alternatively, you can buy my new-ish book—FLUKE: Chance, Chaos, and Why Everything We Do Matters.