Experiment with Everything

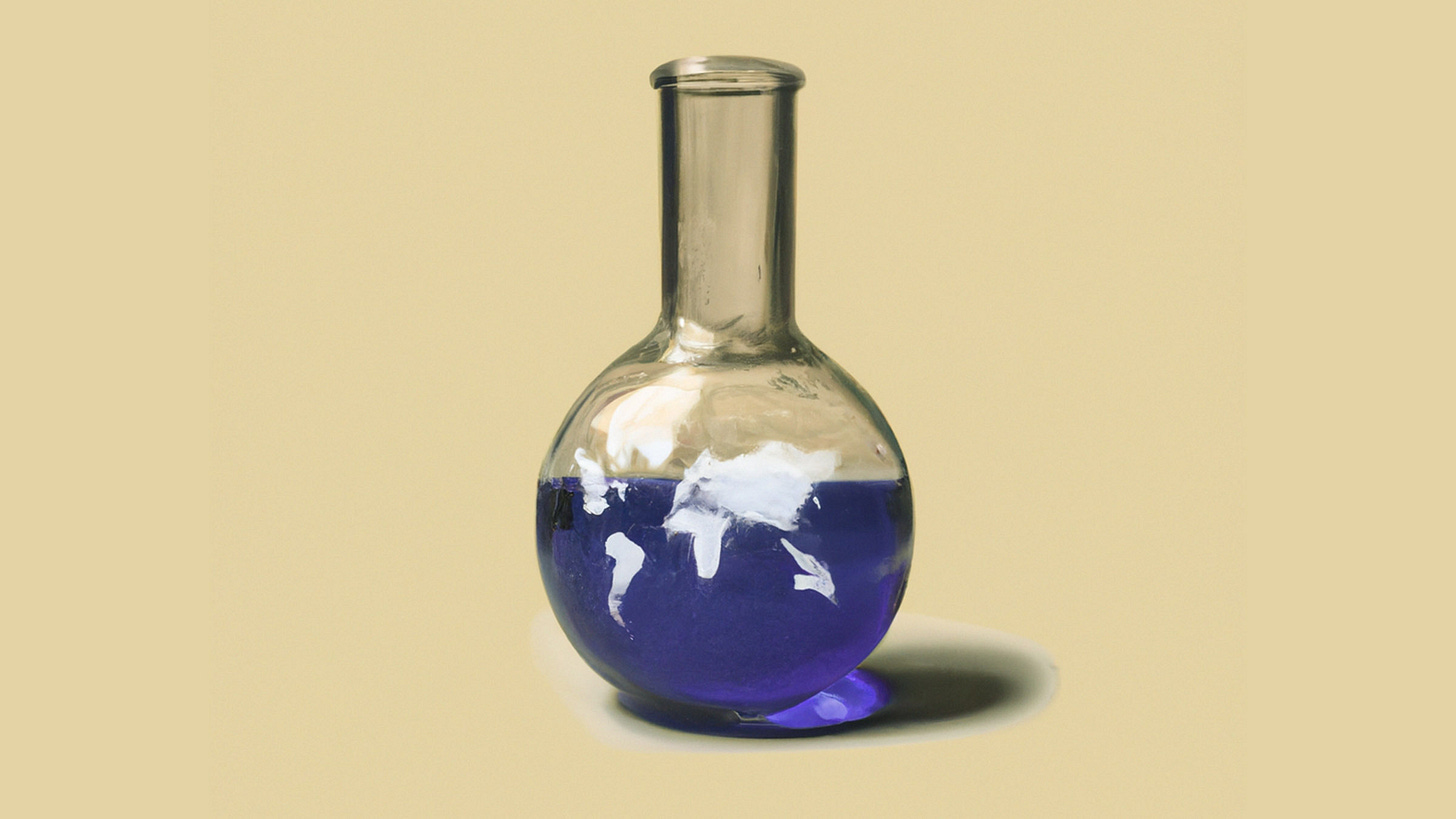

One man randomized his life. He teaches us why we need much more trial-and-error experimentation—in our lives and in public policy. Here's how it might work.

Thank you for reading The Garden of Forking Paths. Please consider supporting my work with a paid subscription, as I rely exclusively on the generosity of reader support.

Act I: How to Randomize Your Life

One Friday night, an Uber showed up outside Max Hawkins’s apartment in San Francisco. He had no idea where it would take him, but Hawkins got in.

As it coursed through the streets, he squinted out the window, but didn’t recognize the neighborhood. It was an area of the city he’d never been in before. Finally, the car pulled to a stop. “We’ve arrived,” the driver told him. Hawkins, unsure of where he was, looked for a sign and found one: “San Francisco General Hospital Psychiatric Emergency Center.”

Hawkins was not being committed. Instead, he’d ended up at the mental hospital, randomly. It was the beginning of an experiment, in which he randomized his life.

Working as a software engineer at Google, Hawkins had found himself living out the philosophy of optimization that he embedded in software code. He scoured reviews for the best coffee shop in town, ensuring he wouldn’t make the rookie error of wasting time somewhere that wasn’t optimal. He figured out the fastest journey to work, riding his bike door-to-door in an average of 15 minutes and 37 seconds. He was exploiting life to the fullest, one metric at a time.

But one day, Hawkins had a troubling epiphany: was this really living?

To inhabit such an optimized existence meant that he was following preferences that may have kept him from exploration. In a radical rejection of his old ways, he put his programming skills to work, and designed a series of algorithms that would randomize as many aspects of his life as possible. The arrival at the psychiatric hospital was the first one, for a program he designed that would summon an Uber and take him to a random destination in the Bay Area.

He was hooked.

For the next several years, Hawkins increasingly deferred to random algorithms when making choices. He ate food that was randomly chosen for him (and struggled when the Gods of Randomness didn’t dictate a morning cup of coffee). He wore clothes that were randomly selected, accumulating a hodgepodge wardrobe. Hawkins even began living in new cities for two or three months at a time—Dubai, Taipei, Mumbai, even a goat farm in rural Slovenia—randomly picked for him by digital software he designed. He was the plaything of random forces, and he embraced every new adventure.

Once he arrived somewhere new, he would attend random public events that were posted on Facebook. Through this method, he attended yoga classes in Mumbai. He took a three hour course on how to humanely capture feral cats. Hawkins even got a tattoo on his chest, of an image that was randomly selected from the internet.

“Paradoxically, giving up control made me feel more free,” Hawkins says. “My preferences had blinded me to the complexity and richness of the world.”

Hawkins was, in an extreme way, trying to reject the feeling that an algorithm was optimizing his life, based solely on his past preferences. And yet, that’s what often happens to us as we live a reactive life, scrolling through posts selected for us on social media, clicking from one YouTube clip to the next one in the suggestions bar.

This is by design. “I actually think most people don’t want Google to answer their questions,” Eric Schmidt, the billionaire former CEO of Google once said. “They want Google to tell them what they should be doing next.” Hawkins took that message in stride, but flipped its logic on its head.

Rather than optimizing based on what Google knew about him, he had algorithms make decisions without any reference to who they were aimed at, a random bolt from the digital blue. Hawkins found it liberating, for a time.

There is no need to randomize your life like Hawkins did. It’s not sustainable. Most of us would find it overwhelmingly bewildering and often miserable. Too much experimentation isn’t enjoyable. There are good reasons for why Hawkins no longer lives in a new place every two to three months.

But learning a few lessons from the Max Hawkins school of life would do us all good, because experimentation is the key to not just surviving, but thriving—in our lives and in our societies.

Act II: “Evolution is Cleverer Than You Are”

Every living organism, including us, faces a constant, relentless tradeoff: to explore or to exploit. To explore is to try something new. To exploit is to cash in on what you know. In the banal terms of our modern lives, trying a new restaurant is an explore strategy. Going to your favorite restaurant is a way to exploit existing knowledge.

Life explores in two ways, one through behavior, another through the hidden genetic recipe that makes us who we are.

Imagine you’re an antelope, scraping by on a barren hillside, munching on the desiccated remnants of whatever plant life you can find. Then, one day, when you’re particularly hungry and emaciated, your diminutive antelope brain conjures up a profound new idea: to climb up the hillside, and explore what lies beyond its peak.

That strategy comes with risk: what if a predator lurks below? But it also comes with potentially enormous rewards, juicy plants in abundance, with tasty insects flitting above their green shoots.

Exploration provides fresh knowledge about the world—information that you didn’t previously have. That allows better decision-making and a more calibrated way of life. There are risks, yes, but the rewards are usually much greater.

Life that doesn’t explore gets stuck, unaware of what delights might await, just out of reach. It’s a rut-based existence, and a precarious one too, because as soon as the rut becomes uninhabitable, you’re toast. And that’s why every successful living creature, long into the distant mists of evolutionary time, has made exploration a central part of their survival strategy.

Then, there’s nature’s invisible exploration, accomplished through evolution by natural selection, often powered by seemingly random mutations. A bit like Max Hawkins, it’s an unguided trial-and-error approach, as random mistakes in genetic transcription test out little tweaks to existing lives, sometimes subtly altering behavior and other times establishing entirely new species.

This mechanism of exploration—sometimes guided by behavioral cues and other times a more random genetic experiment—is astonishingly effective. In fact, it’s the underlying wisdom to life’s extraordinary endurance, lingering on whether walloped by asteroids or threatened by a changing climate.

This has given rise to Orgel’s Second Rule, named after the British expert on the origins of life, Leslie Orgel. It’s a simple rule, but a powerful one:

“Evolution is cleverer than you are.”

We, unlike evolution by natural selection, can apply rigorous rational thought, extraordinary reason, logical inference, and deductive thinking to any problem we face, like no species before us. Nevertheless, unthinking evolutionary processes will beat us in the survival sweepstakes, because when you apply random trial-and-error over billions of years, nature comes up with solutions that would never occur to us in our wildest dreams.

Experimentation is life’s secret to success.

And when life explores, aggregating knowledge and tapping into new information about what works and what doesn’t, it doesn’t just survive—it flourishes.

It’s a lesson we too readily forget, stuck in our routines, our checklist existence, with lives that are too often scripted months, even years in advance, cramming ourselves into the boxes of Google calendars with repeating events and an utter lack of serendipity. In the balance between explore and exploit, we are too often led astray by a fixation on exploitation without experimentation.

This modern malaise—which plagues many of our individual lives—also plagues society. Some of us may not feel keen on becoming more Max Hawkins-like in our daily lives, channeling evolutionary trial-and-error living. But all of us should see the sagacity of introducing more experimentation to public policy, so we can solve the most pressing problems we face.

Act III: “A fool is someone who never tried an experiment”

Comparatively speaking, humans only figured out the value of controlled experiments relatively recently. While he’s not exactly a household name, Ibn al-Haytham, an Arab scholar who lived in the late 10th and early 11th centuries and researched optics, is regarded as the early pioneer of the experimental method. Since then, experiments have unleashed revolutionary technologies and changed the world.

Unique insights can be gleaned from experiments, which is why Erasmus Darwin, the grandfather of Charles Darwin, once quipped that “A fool…is a man who never tried an experiment in his life.” And within the world of experiments, one method now tends to reign supreme: randomized controlled trials.

In recent decades, those of us who are social scientists—perhaps with a bit of envy for our natural science counterparts—have gotten more interested in using experiments to answer difficult questions. But there’s a problem: many of the questions we want to answer aren’t testable in a laboratory setting.

Take, for example, my doctoral research question: do rigged elections increase the likelihood of future coups and civil wars? To do a proper randomized controlled trial, you’d need to randomly select a set of countries, randomly sort them into two groups, then rig elections in half of them, not rig elections in the other half, and see what happened. It’s not just mad-scientist-levels-of-unethical, it’s also logistically impossible.

Much that is important remains experimentally untestable.

Even when social questions are testable, humans are quite unlike chemical compounds. We behave differently when we know we’re being studied (including phenomena now often known as the Hawthorne Effect and the John Henry Effect).

Plus, unlike baking soda and vinegar, which fizz no matter who mixes them together, what time of day it is, or the country in which the experiment is being carried out, our behavior is highly sensitive to context and culture, which makes experimental evidence more difficult to generalize.

In other words, it’s impossible to say that the findings from an experiment in the United States will apply equally well to, say, Togo. Heck, who’s to say that an experiment in rural Florida will give us any insights into Manhattan?

Despite those caveats, there are ways that experimentation can reveal profound truths, which we can use to make better judgments. For example, in the earlier days of social science experiments, researchers sent out mailings to American voters encouraging them to show up to the polls. The idea was to test how much social pressure affected voter turnout.

The researchers experimentally varied the messages in the mailings, so some people only got a message encouraging them to vote, while others were told that their neighbors would be told about which households voted and which didn’t as part of their study on turnout rates. One of the mailings had the headline: “What if your neighbors knew whether you voted?”

Lo and behold, the study showed that social pressure works! People go to the polls more when they think their neighbors will know whether they voted or not. Whether you agree with the research method as an ethical intervention or not, it provided insights that weren’t possible through other forms of research, simply because they simultaneously tried a few different approaches and randomly allocated who got which mailing. In short, they explored through experimentation.

And yet, it’s depressingly foolish how little we experimentally test various potential public policy ideas. We completely ignore Orgel’s Second Rule, and imagine ourselves clever enough to simply dream up a solution, implement it, then stick with it indefinitely, even when it’s not working. We stay stuck in exploit mode, even when our societies are crumbling around us, like the antelope who will starve to death on a hillside rather than climbing over the peak to discover a better fresh start.

Consider how we make laws. It’s bizarre. Most government policies remain based on hunches, what lawmakers say will work, rather than by testing various options to verify what works best. No experiments done, no evidence required.

Nature’s wisdom is here for the taking: exploration and experimentation works. We ignore it. What in the world are we thinking?

I wrote about how this might function in practice a few years ago in The Washington Post, with an effort to test various approaches to tackling homelessness in Canada.

In early 2018, a charity partnered with the University of British Columbia and effectively started handing out bags of cash to homeless people in Vancouver. Fifty lucky individuals received a one-time lump-sum payment of $7,500 Canadian dollars. They also received free career coaching to foster core life skills and help them get back on their feet. At the same time, 65 other homeless people were given access to the coaching but not the cash.

Researchers tracked what happened to the two groups. What they found was astonishing: Those who were given the lump sum mostly invested in themselves, contrary to harmful stereotypes about homeless people. The group that received no-questions-asked money ended up in stable housing faster than the control group. They spent 39 percent less than they had previously on alcohol and drugs. And, in the process, they saved Canadian taxpayers an estimated $8,100 per person — a cumulative savings of nearly half a million dollars for just 50 homeless people.

That experiment showed that, at least in that local context, the best way to solve the problem—for both the homeless people and for the taxpayer—was to just hand out bags of cash. Blinded by dogma, that solution has rarely been tried. Freed from dogma, with an outside-the-box experiment, they found a better solution.

There’s a hidden secondary benefit to experimentally verified public policy solutions: they can help overcome polarization. As I’ve written previously in this newsletter, what we often refer to as polarization can sometimes be better understood as knowingness, in which everyone already thinks they know the answer to every question, guided by ideology, intellectually incurious, unwilling to explore new terrain.

Sometimes, citizens diverge because of radically different values. But often, partisan divides persist because people have rival explanations for how to solve stubborn problems—and they disagree over what will work best. Experimental public policy—with randomized controlled trials, whenever possible—allows you to test, verify, and then move on.

It’s never going to be quite so clear-cut as we might hope, but evidence from a trial-and-error approach will help. And all of it can be done routinely and cheaply, rolled out randomly to various areas, so that—within ethical regulations—only small numbers of people are guinea pigs before a policy is tested more widely. Those who object to the idea forget an obvious truth: every new policy is an experiment. Isn’t it better to conduct experiments that at least give us evidence about which option is best?

And yes, we should try more off-the-wall ideas out too, Max Hawkins-style, because the best solutions aren’t always intuitive or obvious. That doesn’t mean we should all start getting inked, our chests emblazoned with images randomly selected from the internet. But it does mean that harnessing a little bit more evolutionary wisdom—and putting ourselves in explore mode a bit more often—would do all of us, and our societies, an enormous amount of good.

Thank you for reading The Garden of Forking Paths. I rely on reader support, so please consider upgrading to a paid subscription if you want to support my work—and, in doing so, keep these words coming, beamed straight from my brain and fingertips to your inbox.