Did leaded gasoline cause a huge spike in crime?

The Lead-Crime Hypothesis—that the toxic effects of leaded gasoline explain big spikes in crime—offers convincing evidence and helps explain why violent crime fell so much from the 1990s to today.

Thank you for reading The Garden of Forking Paths. If you value my work and want to allow me to do more of it, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription.

The Mass Murderer You’ve Never Heard Of

Who killed the most people in human history?

It’s not Mao, or Stalin, or Hitler. Instead, it’s someone you’ve probably never heard of.

In 1944, Thomas Midgley Jr. ended his address to the American Chemical Society with these two lines:

Let this epitaph be graven on my tomb in simple style / This one did a lot of living in a mighty little while

The epitaph would have been more accurate to say he did a lot of killing in a mighty little while, because Midgley arguably helped cause the deaths of significantly more than 100 million people, without perpetrating a genocide or gracing a battlefield.

But Midgley may also have unleashed waves of violent crime across the world, leading to an unprecedented surge in murders, rapes, shootings, and stabbings—for decades.

So, why have so few people heard of Midgley, and how could one man possibly create a worldwide crime wave?

Knock Knock Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door

In the early 20th century, as cars were becoming more commonplace, engine knock was the scourge of the motorist. Combustion engines weren’t reliable.

In 1921, Midgley discovered that a compound known as Tetraethyl Lead, or TEL, could stop engine knock if added to gasoline. But lead was known to be toxic, so General Motors patented the additive as “Ethyl.” The invention—and its widespread use—revolutionized combustion engines and created high octane fuel at low cost.

Warning signs lurked from the beginning. In the middle of 1924, Midgley spent several months in Florida recuperating from lead poisoning. After recovering, he recognized that his invention might flounder if others understood its toxicity, so he held a press conference in October 1924 to demonstrate how safe it was. Producing a container of tetraethyl lead, Midgley washed his hands with it.

On November 10, 1924, TIME magazine ran a story about poisonings at a tetraethyl lead plant in New Jersey—and didn’t mince words:

Last week a man suddenly became raving mad. He was taken to a hospital in Manhattan where he soon died. Others became affected. Within a few days, five men, all raving mad and confined in straight-jackets, died…They probably breathed the fumes of the poisonous stuff. Apparently the effect of taking the poison in this way is cumulative and not felt until a considerable dose, possibly a fatal dose, has been received.

The tetraethyl lead plant became known informally as the “loony gas building.”

The TIME article also presciently warned that the threat from the fumes of gasoline with tetraethyl lead posed a hazard to the entire public.

These were not new revelations. Lead poisoning was known even to Vitruvius, a Roman architect who lived in the first century BC. He warned of Rome’s lead pipes for transporting water, noting that lead workers “were pallid colour; for in casting lead, the fumes from it fixing on the different members, and daily burning them, destroy the vigour of the blood.” (The Latin word for lead, plumbum, is where we get the word for plumbing, and is also the reason why lead is Pb on the periodic table).

From the beginning, then, everyone working on tetraethyl lead knew the truth: it was lucrative poison.

Nonetheless, General Motors and Standard Oil created the Ethyl Corporation. Frank Howard, the vice president of the company, hailed leaded gasoline as “a gift of God” that was “essential in our civilization.” The DuPont Corporation got in on the action. The poison spread, as leaded gasoline burned, while cars became a staple of daily life.

By the 1960s, airborne concentrations of lead averaged more than 1,000 nanograms of lead per cubic meter in many parts of the developed world, compared to around 10 nanograms today. Why the rapid fall? The evidence kept piling up that leaded gasoline was toxic, leading to it being banned at various times across the world: 1990 in Canada; 1996 in the United States and New Zealand; 2000 in the United Kingdom and France; 2002 in Australia. From 1980 to 2022, lead emissions fell in the United States by 99 percent.

The Lead-Crime Hypothesis is Born

In 1994, Rick Nevin was evaluating whether it was necessary to remove lead paint from old houses in his capacity as an adviser to the US Department of Housing and Urban Development. The negative effects of lead were widely known, but evidence was mounting that children exposed to lead would have worse outcomes throughout the rest of their lives. For example, as this chart from Nevin shows, as lead exposure increases, IQ points decrease—dramatically.

But it wasn’t just IQ. Lead exposure was known to create severe behavioral problems in youth, too. This prompted Nevin to look into a question nobody had investigated before: could lead exposure be linked to juvenile crime?

In the 1990s, criminologists predicted a surge in violent crime. There was to be a demographic bulge of young males, which, if past was prologue, would lead to a big spike in burglaries, rapes, and murders. The juvenile bulge came. But all the criminology models were wrong: crime didn’t spike. It plummeted, faster and sharper than ever before. This perplexed experts, who used newfound statistical techniques unleashed by computing to try to understand it, to no avail. They were stumped.

One man wasn’t stumped: Rick Nevin. He came up with a hypothesis that hadn’t occurred to the best minds in criminology, who were focused solely on policing strategies, demographic trends, all the usual suspects in explaining crime rates.

As Kevin Drum reported in Mother Jones a decade ago:

If you chart the rise and fall of atmospheric lead caused by the rise and fall of leaded gasoline consumption, you get a pretty simple upside-down U: Lead emissions from tailpipes rose steadily from the early ’40s through the early ’70s, nearly quadrupling over that period. Then, as unleaded gasoline began to replace leaded gasoline, emissions plummeted.

Intriguingly, violent crime rates followed the same upside-down U pattern. The only thing different was the time period: Crime rates rose dramatically in the ’60s through the ’80s, and then began dropping steadily starting in the early ’90s. The two curves looked eerily identical, but were offset by about 20 years.

Nevin’s research found a clear lag, and it’s a striking correlation, so long as you offset the dates by a few decades. See this chart from Nevin’s US data, made by Mother Jones:

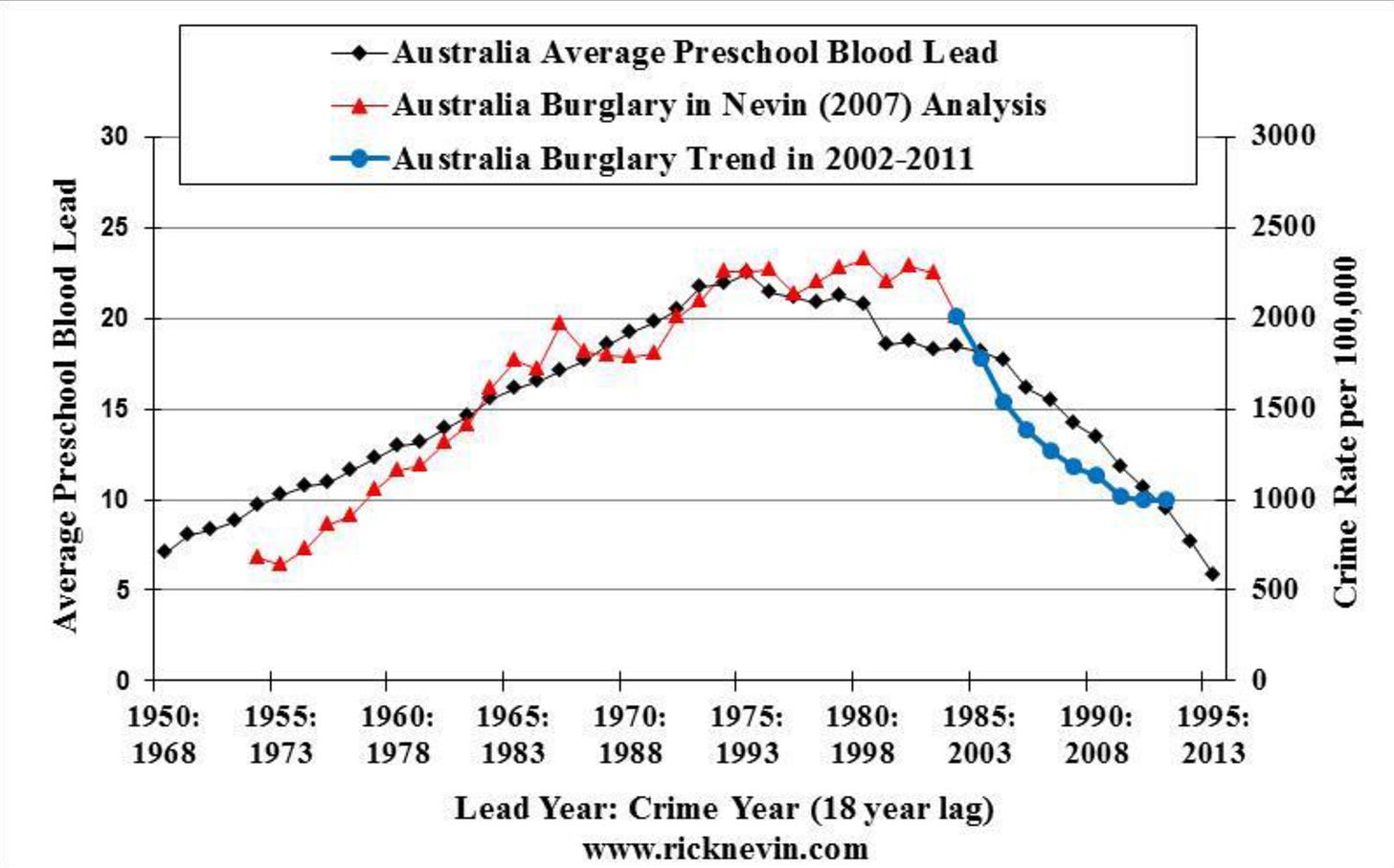

Or this one, from Australia:

Or this one from Britain:

Nevin’s book, Lucifer Curves, along with several peer-reviewed academic studies, lays out a remarkably robust relationship. As Nevin told me when I interviewed him:

“The lead-crime relationship has been clearly demonstrated in studies across time, space, countries, and cities…an extreme spike in St. Louis murders occurred about 20 years after the opening of a massive lead smelter there; and the first use of the term “juvenile delinquency” was recorded in England after an early-1800s surge in lead paint use…Very few people are aware of how universal the lead crime relationship has been.”

In an academic paper published more than two decades ago, Nevin found a statistical bombshell: lead levels seemed to explain 90 percent of the variation in crime rates in the United States between 1960 and 1998.

Correlation, yes, but causation?

We all know correlation and causation are not the same, so there’s good reason to apply a healthy dose of skepticism to neat graphs that purport to explain a major social trend with a single variable. After all, global society is a vastly complex system of more than eight billion interconnected humans, and rarely can a single cause be teased out of that complexity to provide clear, simple explanations.

But Nevin’s case for the lead-crime hypothesis—later taken up by Jessica Wolpaw Reyes at Harvard (now at Amherst College)—is particularly strong for two reasons:

The link between lead exposure and future behavioral problems, including violent aggression, is well documented. Studies show a clear link between childhood lead exposure and lasting negative distortions of adult personality. (Studies have shown a link between childhood lead exposure and future crime in Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Charlotte, and St. Louis, for example).

Because leaded gasoline was phased out at various times in different countries, it has produced a “natural experiment,” in which the explanatory variable (lead exposure) varies across time and space, allowing researchers to examine whether lead is a major contributing factor or not (the evidence shows it is, in a variety of different times, in different environments).

Why are barns red? Or, rural murder rates and lead paint

These correlations even hold across historical patterns—in the most extraordinary ways. As Drum reported in 2015, Nevin’s research examined the rise of lead paint in rural America to see if crime rates spiked after it became more widespread.

In the 19th century, only professional painters could afford leaded paint, so most rural American farmers instead “mixed linseed oil with red rust to kill fungi that trapped moisture and increased wood decay.” This gave rise to the stereotypical red barn—a tradition that persists to this day across rural America. At the same time, there was a major divide in murders between urban and rural America: the murder rate was much higher in urban areas than the countryside for most of the 1800s.

Then, through the expansion of the railroads, the advent of reliable rural postal service, and the rise of mail order catalogs, leaded paint became accessible to rural America in the 1890s. Fast forward two decades, and what happens? You guessed it: murder rates in rural areas skyrocketed, nearly matching those in big cities. (Alone, this is weak, anecdotal evidence, but within the context of the other academic literature, it’s yet another brick in building a solid case for the lead-crime hypothesis).

Indeed, in the longer span of American history, there were two major spikes of lead exposure: first, with paint, then with gasoline. So, if the theory is right, there should be two peaks, not one, both lagged about two decades after the use of lead became more widespread. Let’s turn to the chart:

I’m a social scientist, though, and it’s our job to be skeptical. There are plenty of potentially confounding factors. Humans are complex creatures and our societies are the most complex entities in the universe. That made me seek out meta-analyses and other rival critiques…and I came away convinced that Nevin, Wolpaw-Reyes, and Drum (among many others) are right: lead exposure has, in my view, increased crime rates wherever it has gone. It doesn’t explain everything, and plenty will quibble about the degree to which lead is the culprit. But lead toxicity is clearly a key explanatory variable in trying to understand the variation in crime rates across time and space.

Where have all the juvenile criminals gone?

Nevin’s data also helps to explain a seemingly inexplicable trend: that young criminals in the United States are becoming far scarcer than they used to be:

There’s an obvious retort: that this just reflects a less punitive mentality in criminal justice reform, such that we’re diverting rather than locking up young offenders.

I put this to Nevin, who pointed me to research by Richard Mendel, who crunched the numbers and convincingly argues that “the sizable drop in juvenile facility populations since 2000 is due largely to a substantial decline in youth arrests nationwide, not to any shift toward other approaches by juvenile courts or corrections agencies once youth enter the justice system.” We haven’t become more lenient. Young people are just committing fewer crimes. Why? The lead-crime hypothesis provides one possible explanation.

To date, the lead-crime hypothesis hasn’t had the impact it deserves—and that’s partly because it didn’t align with existing criminology theories. Fancy sociological models were all the rage in the 1990s and the new methodological toys of ever-more complex regressions seemed more sophisticated than a guy at Housing and Urban Development who developed an explanation that derived from correlations with a single environmental factor—not policing, or deprivation, or demographics.

The lead-crime hypothesis also highlights the problem of hidden variables in any quantitative analysis. You only measure and compute what you think is important. But until Nevin, nobody—and I mean nobody—was including environmental exposure to neurotoxins in their quantitative society-wide criminology models. Who knows if they ever would have if Nevin hadn’t raised the issue due to his direct expertise on lead.

We need a little less hubris when we model society and a little more understanding that we will always need subject-matter experts to develop hypotheses, not just ever-bigger computers to crunch numbers, if we want to understand our world.

Midgley Meets His End

To conclude, we return to that unfortunate inventor, Thomas Midgley Jr., a man who—as Bill Bryson put it—had “an instinct for the regrettable that was almost uncanny.” Well, Midgley wasn’t done doing damage. Later, he also invented some of the first CFCs, later known as Freon, which punched an enormous hole in the Ozone layer, causing millions of otherwise avoidable skin cancer deaths. Lead poisoning, largely unleashed by tetraethyl lead in gasoline, may have caused significantly more than 100 million deaths, with recent studies showing the ongoing harms may be even worse than previously thought.

Midgley likely would have died from lead poisoning if he had a chance to reach older age. Instead, after contracting Polio in 1940, he became severely disabled, so he invented an elaborate system of pulleys and ropes to lift himself out of bed. In an unfortunate accident, he became entangled in his contraption, couldn’t escape, and died from strangulation—adding himself to the gargantuan tally of poor souls killed inadvertently by one of Thomas Midgley Jr.’s ingenious, but deadly, inventions.

Thank you for reading The Garden of Forking Paths. These articles take weeks to research and write, so if you enjoyed it, learned something, or just want to support my work, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription. Every person counts. Your support allows me to focus more of my time on research—and makes this sustainable.

Brian, a brilliant paper! Congratulations.

One added thought regarding use of lead by the Romans. This not only occurred in plumbing, but also in the use of lead cups for drinking. Lead was used to give weight, leaf gold to make the cups also look like gold. Over time and with the chemical effects of wine, the gilding gradually wore off and the average consumer drank wine laced with lead. There is a theory that this was a significant contribution to the decline of the Roman Empire.

Stunning that action didn’t happen earlier. Tetraethyl lead, just from its name, a chemist should immediately be able to tell this is a highly toxic compound. If one was tasked with finding a chemical to efficiently deliver lead to biological systems, tetraethyl lead might be a prime candidate, might even be the first one to try.

But proving causation like you mention is really difficult, especially for humans. We have a whole lot of ethical considerations - can’t just assign people to groups and feed some of them a bunch of poison to study the effect. One cannot control isolate an individual’s environment scientifically for any significant length of time either. So, you don’t have complete data to prove a case.

And if you have an interested party on the other end that is printing money by marketing the dangerous product, they can be very effective running interference, stymie public awareness enough to prevent regulation. We saw this with tobacco a generation ago and climate change for the past several decades. It now seems there is PR misinformation playbook that is very effective at enabling continuation of harmful business practices.

Thanks again for another eye opening article!